calsfoundation@cals.org

Slavery

American chattel slavery was a unique institution that emerged in the English colonies in America in the seventeenth century. Enslaved peoples were held involuntarily as property by slave owners who controlled their labor and freedom. By the eighteenth century, slavery had assumed racial tones as white colonists had come to consider only Africans who had been brought to the Americas as peoples who could be enslaved. Invariably, the earliest white settlers who moved into Arkansas brought slave property with them to work the area’s rich lands, and slavery became an integral part of local life. The enslaved played a major role in the economic growth of the territory and state. Their presence contributed to the peculiar formation of local culture and society. The existence of slavery ultimately helped to determine the political course of the territory and state until the end of the Civil War and slavery’s abolition in 1865 with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Slavery’s Origins in Arkansas

The first people enslaved by Europeans entered what was to become Arkansas in about 1720, when settlers moved into the John Law colony on land given to them on the lower Arkansas River by the king of France. The Law colony failed within two years, but a small number of inhabitants, including some who probably were enslaved, remained in the area for the rest of the French and Spanish territorial periods. In the first official U.S. census of Arkansas as the “District of Louisiana” in 1810, the census takers found 188 slaves in a total population of 1,062 people. The development of this area and its creation as Arkansas Territory in 1819 spurred a rapid growth in the enslaved population. By 1820, it had risen to 1,617. These trends continued through the territorial period and up to the Civil War. By 1830, the enslaved population reached 4,576; then 19,935 in 1840; 47,100 in 1850; and 111,115 in 1860. As the enslaved population grew, it also constituted a larger and larger portion of the total population, growing from eleven percent in 1820 to twenty-five percent by 1860.

Enslaved people lived in every county and in both rural and urban settings in antebellum Arkansas. Historian Orville Taylor estimated that roughly one in four white Arkansans either owned slaves or lived in families that did. Many more probably benefited from slavery, however, as leasing the enslaved was not an uncommon practice. Although slavery clearly touched the lives of many white Arkansans, most slave-owners possessed only a few. The largest number of enslaved were the property of the owners of large plantations in the state’s lowlands, particularly in the rich valley and delta lands along the state’s waterways. A relatively large slave holding would have been ten people, a work force valued at about $9,000 on the average in 1859, an amount equal to approximately $200,000 in 2002. By 1860, seventy-three percent of of the enslaved population were on plantations and farms of that size. They were owned, however, by only about twenty-six percent of the state’s slave owners. Elisha Worthington of Chicot County was the state’s largest slave owner, holding more than 500 people on the eve of the Civil War.

Legal Protection for Slavery

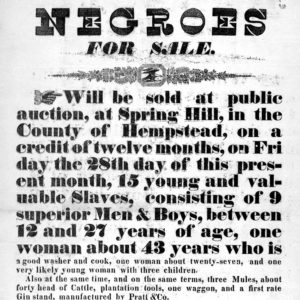

The Code Noir, or Black Code, of French Louisiana and additional legislation during Arkansas’s territorial and statehood periods established the basic legal definition of slavery and helped determine the world in which the individual slave lived. By law, an enslaved person was subject to all laws involving personal property. Like cattle, horses, or other types of possessions, slaves formed part of the owner’s estate. This meant that they had no legal identity of their own, making it impossible for them to engage in contractual relations for labor, business, or even marriage. The enslaver, on the other hand, could dispose of slave property just like any other asset, including hiring them out, selling them, or even sending children away from their parents. Heirs inherited slaves upon an owner’s death.

Even though it defined people held in slavery as less than human, the law recognized the enslaved as a unique form of property. Numerous statutes made it clear that the white community knew their slaves were human beings and could not be dealt with in the same way as livestock. Slaves had to be controlled, and laws attempted to achieve that goal and provided for punishment of those who broke these laws. Statutes restricted their movement, required passes to leave their home plantation, limited their rights of assembly, and prohibited their possession of firearms, clearly indicating that whites saw their property as restless and potentially dangerous. An 1825 law created the slave patrol, an institution that enforced such limits across the countryside, the existence of which further indicated the contradictory character of white perceptions of their slave property. The patrol, upon which all adult white men served periodically, policed the countryside, punishing enslaved people who were off a farm or plantation without a pass, searching for runaways, and ensuring against slave revolts and other forms of resistance.

Contemporary whites often looked at their peculiar institution as a benevolent one and saw the lack of any notable slave revolts in Arkansas as reflecting its benign character. The majority of those enslaved probably did not see it that way. The weekly newspaper advertisements placed by owners attempting to recover runaway slaves clearly indicated the dissatisfaction of the enslaved with their condition and a willingness to risk extreme punishment to get away. The frequent need of enslavers to resort to physical punishment to secure obedience also indicates the refusal of individuals held in slavery to be satisfied with their condition. Impudence, disobedience, and a refusal to work—all behaviors that led to whippings by Arkansas planters—demonstrated the efforts by those enslaved to establish some degree of personal independence within the system of slavery. In the end, only the use of force made possible this critical labor system through the antebellum years.

Economics of Slavery

Slavery served primarily to provide labor for the state’s economy, and the enslaved added greatly to its development. Slavery made possible the rapid expansion of the cotton frontier within Arkansas, and slave labor contributed greatly to the state’s material wealth, adding at least $16 million to the economy each year and making Arkansas the sixth largest cotton producer in the United States by 1860. Historians have debated whether or not slavery was profitable for the South, but in Arkansas there is no question that slave labor produced profits for some individual enslavers. Nothing shows more clearly that contemporaries considered the system profitable as much as the inflation in the price of slaves through the antebellum period. Orville W. Taylor has shown that average prices in Arkansas rose from $105 in the 1820s to nearly $900 by 1860, taking into account children as well as adults. Enslaved adults with skills such as carpentry or blacksmithing could bring enormous prices, with some such slaves costing as high as $2,800. These prices were comparable to approximately $2,200, $20,000, and $61,000 in 2002 dollars.

A Slave’s Life

Much is known about slavery from the perspective of whites, but less is known about the enslaved themselves, especially from their point of view. White sources affirm that slave labor often was harsh. The vast majority of slaves worked as field hands, usually from sunrise to sunset every day of the week except Sunday. They devoted most of their time to the cultivation of cotton—plowing fields and planting the crop in late February, keeping the fields clear of grass and weeds until what was called lay-by time. At this point, usually in July, crops generally did not require intensive cultivation, and field work ended. Field slaves then labored at building and repairing fences, clearing land, and performing a wide variety of other plantation chores. All hands went back into the fields in August, however, when picking began and stayed there often until the end of the year. Some of the enslaved did not engage in field work, however. Tending livestock, working as skilled craftsmen, or performing housework were typical of the jobs performed by those not in the fields. Whatever job the enslaved performed, the owner usually attempted to extract as much labor from them as possible. Despite the power of the enslaver, however, slaves proved to be very resourceful at controlling their working conditions within limits. They often could secure concessions from masters or overseers by sabotaging crops or outright defiance against their demands.

Those held in slavery usually lived in small log or lumber cabins in separate quarters from their white enslavers, although some might live with their owner on a small holding. Slave cabins usually had dirt floors, contained very little furniture, and perhaps even lacked doors and windows. Slaves’ clothing was usually manufactured on the plantation out of coarse or low-quality cloth. Owners usually purchased shoes, but the enslaved often did without them except in the winter. The diet of people in slavery varied from plantation to plantation but mostly consisted of pork and corn supplemented with some vegetables grown on the farm. In some cases, the supplements came from plantation gardens. Some planters allowed slaves to tend small patches of their own. In cases where a master allowed slaves to carry arms and hunt, they added wild game and fish to their diet. The diet was barely adequate, as the death rate of the enslaved relative to whites showed. While barely adequate, slaves survived such conditions and, in Arkansas, possibly did relatively better than those in other Southern states. The 1850 census indicated that the death rate among the enslaved in Arkansas was 1.83 per thousand, considerably lower than the overall national average of 2.13. On the other hand, the slave death rate was thirty percent higher than that of the state’s free population.

Slave Culture

Less is known about slave society and culture, although it is clear that slaves successfully created unique institutions among themselves despite the limits imposed on them. For the most part, the enslaved attempted to establish family life in the slave quarters even though the law prevented legal marriage. Efforts at reuniting family members who had been separated by owners and at legalizing marriages at the end of the Civil War demonstrate the importance of family to those held in bondage.

A religious life also developed within the slave community, especially variations on Protestant Christianity. Many masters encouraged religion among their slaves, sometimes for benevolent reasons but at times because they believed it would make their property more docile. Slaves quickly transformed the beliefs of their masters, however, into a faith emphasizing equality before God and ultimate release from slavery. Music also constituted an important part of slave culture. As in the case of religion, the enslaved molded their music into a form that voiced their feelings about their enslavement. Even though the connection of most slaves to Africa was remote by the nineteenth century, elements of their African background appeared in their formulation of social and cultural institutions.

The Civil War and the End of Slavery

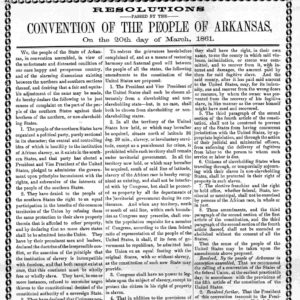

Slavery in Arkansas encouraged the state’s economic development in the antebellum period, but it also played a major role in determining the state’s catastrophic course in the sectional crisis of the 1850s. Through that decade, convinced that a rising Republican Party in the North threatened the future of the institution, leading Arkansas politicians joined others from the South in demanding protection of slavery and threatening a disruption of the Union if the institution’s future was not guaranteed. In the secession crisis during the winter of 1860–1861, following the election of President Abraham Lincoln and the secession of South Carolina, Arkansas leaders such as Congressman Thomas Hindman and Governor Henry Rector pushed for the state to leave, too. Strong Unionist sentiment delayed that action, but ultimately the outbreak of war between the United States and the Confederacy in April of 1861 turned the tide in favor of secession locally.

Ironically, the war contained the seeds of destruction for the institution it was intended to protect. The removal of thousands of white men from the countryside weakened the hold of masters on those in slavery. Even the Confederate government’s appropriation of enslaved laborers changed the character of the institution behind Confederate. Ultimately, however, the successful movement of Union forces into Arkansas in 1862 saw thousands of people flee slavery to secure freedom behind federal lines, and Union victory in 1865 ensured their ultimate freedom. New relationships between those formerly enslaved and white Arkansans would have to be forged after the war, although white people proved reluctant to surrender the power that they had exercised for so long.

| ARKANSAS SLAVE CENSUS COMPARED TO TOTAL POPULATION: 1840, 1850, 1860 (BY COUNTY) | ||||||

| County | 1840 slave | 1840 total | 1850 slave | 1850 total | 1860 slave | 1860 total |

| Arkansas | 361 | 1,346 | 1,538 | 3,245 | 4,921 | 8,844 |

| Ashley | 644 | 2,058 | 3,761 | 8,590 | ||

| Benton | 168 | 2,228 | 201 | 3,710 | 384 | 9,306 |

| Bradley | 1,226 | 3,829 | 2,690 | 8,388 | ||

| Calhoun | 981 | 4,103 | ||||

| Carroll | 137 | 2,844 | 213 | 4,614 | 330 | 9,383 |

| Chicot | 2,698 | 3,806 | 3,984 | 5,115 | 7,512 | 9,234 |

| Clark | 687 | 2,309 | 950 | 4,070 | 2,214 | 9,735 |

| Columbia | 3,599 | 12,449 | ||||

| Conway | 192 | 2,892 | 240 | 3,583 | 802 | 6,697 |

| Craighead | 87 | 3,066 | ||||

| Crawford | 618 | 4,266 | 933 | 7,960 | 858 | 7,850 |

| Crittenden | 454 | 1,561 | 801 | 2,648 | 2,347 | 4,920 |

| Dallas | 2,542 | 6,877 | 3,494 | 8,283 | ||

| Desha | 407 | 1,598 | 1,169 | 2,911 | 3,784 | 6,459 |

| Drew | 915 | 3,276 | 3,497 | 9,078 | ||

| Franklin | 400 | 2,665 | 472 | 3,972 | 962 | 7,298 |

| Fulton | 50 | 1,819 | 88 | 4,024 | ||

| Greene | 50 | 1,586 | 53 | 2,593 | 189 | 5,843 |

| Hempstead | 1,936 | 4,921 | 2,460 | 7,672 | 5,398 | 13,989 |

| Hot Spring | 249 | 1,907 | 361 | 3,609 | 613 | 5,635 |

| Independence | 514 | 3,669 | 828 | 7,767 | 1,337 | 14,307 |

| Izard | 141 | 2,240 | 196 | 3,213 | 382 | 7,215 |

| Jackson | 276 | 1,540 | 563 | 3,086 | 2,535 | 10,493 |

| Jefferson | 1,010 | 2,566 | 2,621 | 5,834 | 7,146 | 14,971 |

| Johnson | 591 | 3,433 | 731 | 5,227 | 973 | 7,612 |

| Lafayette | 1,644 | 2,200 | 3,320 | 5,220 | 4,311 | 8,464 |

| Lawrence | 267 | 2,835 | 388 | 5,274 | 494 | 9,372 |

| Madison | 83 | 2,775 | 164 | 4,823 | 296 | 7,740 |

| Marion | 39 | 1,325 | 126 | 2,308 | 261 | 6,192 |

| Mississippi | 510 | 1,410 | 865 | 2,368 | 1,461 | 3,895 |

| Monroe | 148 | 936 | 395 | 2,049 | 2,226 | 5,657 |

| Montgomery | 66 | 1,958 | 92 | 3,633 | ||

| Newton | 47 | 1,758 | 24 | 3,393 | ||

| Ouachita | 3,304 | 9,591 | 4,478 | 12,936 | ||

| Perry | 15 | 978 | 303 | 2,465 | ||

| Phillips | 905 | 3,547 | 2,591 | 6,935 | 8,941 | 14,877 |

| Pike | 109 | 969 | 110 | 1,861 | 227 | 4,025 |

| Poinsett | 67 | 1,320 | 279 | 2,308 | 1,086 | 3,621 |

| Polk | 67 | 1,263 | 172 | 4,262 | ||

| Pope | 215 | 2,850 | 479 | 4,710 | 978 | 7,883 |

| Prairie | 273 | 2,097 | 2,839 | 8,854 | ||

| Pulaski | 1,284 | 5,350 | 1,119 | 5,657 | 3,505 | 11,699 |

| Randolph | 216 | 2,196 | 243 | 3,275 | 359 | 6,261 |

| St. Francis | 365 | 2,499 | 707 | 4,479 | 2,621 | 8,672 |

| Saline | 399 | 2,061 | 503 | 3,903 | 749 | 6,640 |

| Scott | 131 | 1,694 | 146 | 3,083 | 215 | 5,145 |

| Searcy | 3 | 936 | 29 | 1,979 | 93 | 5,271 |

| Sebastian | 680 | 9,238 | ||||

| Sevier | 725 | 2,810 | 1,372 | 4,240 | 3,366 | 10,516 |

| Union | 906 | 2,889 | 4,767 | 10,298 | 6,331 | 12,288 |

| Van Buren | 59 | 1,518 | 103 | 2,864 | 200 | 5,357 |

| Washington | 883 | 7,148 | 1,199 | 9,970 | 1,493 | 14,673 |

| White | 88 | 929 | 308 | 2,619 | 1,432 | 8,316 |

| Yell | 424 | 3,341 | 998 | 6,333 | ||

| STATE | 19,935 | 97,574 | 47,100 | 209,897 | 111,115 | 435,450 |

| Note: | As the above chart indicates, every county in Arkansas, from the moment of its establishment, recorded the enslaved population in the three censuses taken following the state’s admission to the Union. Twenty counties were created after 1860 from parts of earlier counties; therefore, not every county existing today is shown on the chart. As a percentage of the population, slave populations ranged from less than one percent (in Newton County) to over eighty percent (in Chicot County) in 1860. | |||||

For additional information:

Battershell, Gary. “The Socioeconomic Role of Slavery in the Arkansas Upcountry.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Spring 1999): 45–60.

Bolton, S. Charles. Fugitives from Injustice: Freedom-Seeking Slaves in Arkansas, 1800–1860. Omaha, NE: National Park Service, 2006. Online at http://www.nps.gov/subjects/ugrr/discover_history/upload/Fugitives-from-Injustice-Freedom-Seeking-Slaves-in-Arkansas.pdf (accessed February 10, 2020).

———. Fugitivism: Escaping Slavery in the Lower Mississippi Valley, 1820–1860. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

———. “Slavery and the Defining of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Spring 1999): 1–23.

Cathey, Clyde. “Slavery in Arkansas (Part I).” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 3 (Spring 1944): 66–90.

———. “Slavery in Arkansas (Part II).” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 3 (Summer 1944): 150–163.

Craig, Robert D. “Civil War Breaks the Shackles of Slavery.” Stream of History 53 (2020): 24–40.

———. “Jackson Countians Value Slavery.” Stream of History 53 (2020): 12–23.

Deeben, John P. “Defending the Legal Rights of Former Slaves: Records of the Freedmen’s Bureau Courts in Arkansas.” Arkansas Family Historian 60 (Spring 2022): 8–13.

Duncan, Georgena. “Manumission in the Arkansas River Valley: Three Case Histories.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 66 (Winter 2007): 422–443.

———. “‘One negro, Sarah… one horse named Collier, one cow and one calf named Pink’: Slave Records from the Arkansas River Valley.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 69 (Winter 2010): 325–345.

Durning, Dan. “Henry Jacobi’s Brace Deed: Helping Seven Escaped Slaves as the Confederacy Ended in Little Rock.” Pulaski County Historical Review 69 (Summer 2021): 57–64.

Gigantino, James J. III. “Slavery and the Creation of Arkansas Territory: A Reconsideration.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 78 (Autumn 2019): 231–247.

Gigantino, James J. II, ed. Slavery and Secession in Arkansas: A Documentary History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2015.

Griffith, Nancy Snell. “Slavery in Independence County.” Independence County Chronicle 41 (April–July 2000).

Hancox, Louise M. “Picturing a Nation Divided: Art, American Identity, and the Crisis over Slavery.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2018.

Howard, Rebecca A. “No Country for Old Men: Patriarchs, Slaves, and Guerrilla War in Northwest Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 75 (Winter 2016): 336–354.

Johnson, Walter. River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013.

Jones, Kelly Houston. “Black and White on Slavery’s Frontier: The Slave Experience in Arkansas.” In Race and Ethnicity in Arkansas: New Perspectives, edited by John A. Kirk. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2014.

———. “Bondwomen on Arkansas’s Cotton Frontier: Migration, Labor, Family, and Resistance among an Exploited Class.” In Arkansas Women: Their Lives and Times, edited by Cherisse Jones-Branch and Gary T. Edwards. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018.

———. “Bondswomen’s Work on the Cotton Frontier: Wagram Plantation, Arkansas.” Agricultural History 89 (Summer 2015): 388–401.

———. “Chattels, Pioneers, and Pilgrims for Freedom: Arkansas’s Bonded Travelers.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 75 (Winter 2016): 319–335.

———. “‘Doubtless Guilty’: Lynching and Slaves in Antebellum Arkansas.” In Bullets and Fire: Lynching and Authority in Arkansas, 1840–1950, edited by Guy Lancaster. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018.

———. “The Peculiar Institution on the Periphery: Slavery in Arkansas.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2014. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2044/ (accessed April 28, 2021).

———. “‘A Rough, Saucy Set of Hands to Manage’: Slave Resistance in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 71 (Spring 2012): 1–21.

———. A Weary Land: Slavery on the Ground in Arkansas. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2021.

———. “White Fear of Black Rebellion in Antebellum Arkansas, 1819–1865.” In The Elaine Massacre and Arkansas: A Century of Atrocity and Resistance, 1819–1919, edited by Guy Lancaster. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

Lack, Paul D. “An Urban Slave Community: Little Rock, 1831–1862.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 41 (Autumn 1982): 258–287.

Lankford, George E. “Austin’s Secret: An Arkansas Slave at the Supreme Court.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 74 (Spring 2015): 56–73.

Lankford, George E., ed. Bearing Witness: Memories of Arkansas Slavery: Narratives from the 1930s WPA Collections. 2d ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2006.

Moneyhon, Carl H. “The Slave Family in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Spring 1999): 24–44.

McNeilly, Donald P. The Old South Frontier: Cotton Plantations and the Formation of Arkansas Society, 1819–1861. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Parks-Spencer, Susan. “Rebecca Brown Tolbert and Her Experiences during the Civil War in Prairie Grove.” Flashback 71 (Summer 2021): 73–82.

———. “Remembering the Lives of Robert Kidd and William Clingman Raper.” Flashback 74 (Spring 2024): 2–10.

Pierce, Michael. “‘Adventures. Escape of a Slave.’: An Account of the Flight of Nelson Hackett, May 27, 1842.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 79 (Summer 2020): 133–141.

Rodrigue, John C. Freedom’s Crescent: The Civil War and the Destruction of Slavery in the Lower Mississippi Valley. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2023.

Shafer, Robert S. “White Persons Held to Racial Slavery in Antebellum Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 44 (Summer 1985): 134–155.

Smith, Ted J. “Mastering Farm and Family: David Walker as Slaveholder.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Spring 1999): 61–79.

———. “Slavery in Washington County, Arkansas, 1828–1860.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 1995.

Stafford, L. Scott. “Slavery and the Arkansas Supreme Court.” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Journal 19 (Spring 1997): 413–464. Online at https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1729&context=lawreview (accessed April 20, 2021).

Taylor, Orville W. Negro Slavery in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Thompson, George H. “Slavery in the Mountains: Yell County, Arkansas, 1840–1860.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 39 (Spring 1980): 35–52.

Van Deburg, William L. “The Slave Drivers of Arkansas: A New View from the Narratives.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 35 (Autumn 1976): 231–245.

Walz, Robert. “Arkansas Slaveholdings and Slaveholders in 1850.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 12 (Spring 1953): 38–73.

West, Cane W. “Learning the Land: Indians, Settlers, and Slaves in the Southern Borderlands, 1500–1850.” PhD diss., University of South Carolina, 2019. Online at https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5618/ (accessed November 22, 2022).

Westwood, Howard C. “The Reverend Fountain Brown: Alleged Violator of the Emancipation Proclamation.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 49 (Summer 1990): 107–123.

Zorn, Roman J. “An Arkansas Fugitive Slave Incident and Its International Repercussions.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 16 (Summer 1957): 139–149.

Carl H. Moneyhon

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

African Americans

African Americans Anti-miscegenation Laws

Anti-miscegenation Laws Ashley County Lynching of 1857

Ashley County Lynching of 1857 Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Free Blacks

Free Blacks Slave Literacy

Slave Literacy Toll (Lynching of)

Toll (Lynching of) Grave of Family Slave

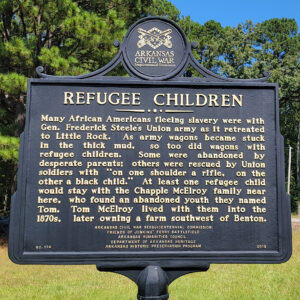

Grave of Family Slave  Refugee Children Marker

Refugee Children Marker  Runaway Slave Article

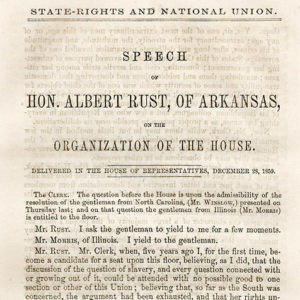

Runaway Slave Article  Albert Rust Speech

Albert Rust Speech  Slave Auction Notice

Slave Auction Notice  Slavery Resolution

Slavery Resolution

White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America by Nancy Isenberg (real history left out in schools; wonder why)

Nothing was said about the injustice to black women in that fact that they were forced into having sex. There is so little justice I can find in my heritage.