calsfoundation@cals.org

William Minor "Cush" Quesenbury (1822–1888)

William Minor “Cush” Quesenbury (the nickname reflecting how the last name should be pronounced) is known for his achievements as a journalist whose essays appeared in national publications; the founder and editor of the South-West Independent at Fayetteville (Washington County), one of the most quoted newspapers in the 1850s; a painter whose sketchbooks cover his trip to and from California during the gold rush; a poet, whose long poem on Arkansas encapsulated the state’s history and people; and a soldier who fought in both the Mexican War and the Civil War. Historians familiar with his accomplishments rank him as one of the most prolific and creative individuals Arkansas ever produced.

Bill Quesenbury was born on August 21, 1822, in newly formed Crawford County of Arkansas Territory. His parents were Henry Anderson Quesenbury and Susan Bean Quesenbury, descendants of the first Quesenburys to settle in Virginia in 1625 and the pioneering Bean family of Tennessee. Although the Quesenbury side played only a minor role in Arkansas history, Quesenbury’s Bean relatives—Robert, William, Richard Henderson, Mark and Jesse—loom large. Quesenbury’s earliest known appearance in Arkansas history came when he was a witness to the Osage looting of his uncles’ salt works in what was then Lovely County (a short-lived territorial creation carved out of Lovely’s Purchase that encompassed the future Benton and Washington counties as well as part of Crawford County in Arkansas and the future Oklahoma counties of Delaware, Adair, Sequoyah, Cherokee, and Mayes).

Quesenbury attended the first school in Fort Smith (Sebastian County). In 1838, he went to St. Joseph’s College, a Catholic institution in Bardstown, Kentucky. The following year, he settled in Van Buren (Crawford County) and began writing for the town’s newspapers, Frontier Whig and the more enduring Democratic Arkansas Intelligencer. The latter publication issued his first nationally recognized writings, “The Upper Creeks” and “The Lower Creeks.” The first essay described a Stamp Dance and provided details on a speech by chief Hopoeithleyhola. Liquor, gambling, and other debaucheries marked the lives of the lower Creeks. Both were reprinted in The Spirit of the Times (1845). Quesenbury followed these with an essay on fishing in Arkansas.

In 1842, painter John Mix Stanley began his two-year tour of the Indian Territory and northwest Arkansas. Quesenbury, who had been drawing since childhood, took advantage of the opportunity to study under him, probably during Stanley’s stay in Van Buren in 1844. In appreciation, Quesenbury later named his first-born son Stanley. Thereafter, he worked on full-length studies and sketches intermittently until this death.

In the late summer of 1845, Quesenbury joined a scouting party of Cherokee interested in settling in Texas. Quesenbury kept a journal of his Texas trip and did not return to Arkansas until early 1846.

The outbreak of the Mexican War in 1846 prompted Quesenbury to join the Arkansas regiment. He wrote a detailed account of the Battle of Buena Vista and, in an extended poem, castigated his friend, Albert Pike. Because Pike’s detachment had been on the other side of the field, Pike had not observed the engagement, which cost the life of the regiment’s colonel, Archibald Yell. Quesenbury’s personal courage in this battle was noted in the dispatches, and his long letter explaining the battle was much reprinted.

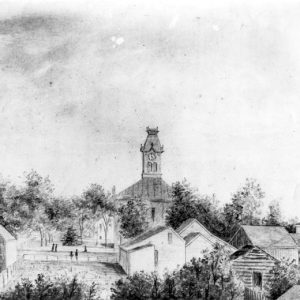

Quesenbury returned to Van Buren in 1847, designed a temperance banner, joined the Presbyterian Church, and married Adaline Parks on November 18, 1847, in Cane Hill (Washington County), where they settled. In 1848, he began teaching school at Boonsboro (Washington County). Quesenbury did not leave with the first party of gold seekers in 1849 but did join the rush to California in 1850, leaving his wife and first-born son, Stanley, behind. A diary and two sketchbooks survive from this expedition, and his detailed drawings of Western sites provide important documentation of historic places. Quesenbury did not prosper as a miner, but he did find work writing first for New Orleans’s California True Delta and then for the new Sacramento Daily Union, whose editor, John F. Morse, promoted public health and scientific agriculture, causes that Quesenbury later supported. His art work included “View of Sutter’s Fort” and pictorial letter sheets showing a view of the Tehama block in Sacramento.

In 1851, Quesenbury returned from California in the company of J. Wesley Jones, whose plans to use daguerreotypes (reportedly 1,500) as the basis for a vast representation of the West called the Pantoscope included signing up Quesenbury as his staff artist. Quesenbury sketched a variety of scenes along the route back through Salt Lake City, Utah, and east into Nebraska. The best of these were differing perspectives on Devil’s Rock, Independence Rock, Chimney Rock (the landmark used for the Nebraska quarter in 2006), and Court House Rock. Apparently, Quesenbury parted with the rest of the company at St. Louis, Missouri, and reached Arkansas in late 1851. Jones took his materials back to Massachusetts, where hired scenic artists made larger renderings. Jones did put on some exhibitions, but the project did not prosper, and only a printed narrative and Quesenbury’s two sketchbooks survive.

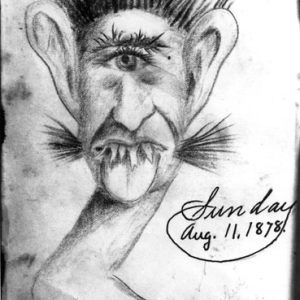

Back in Arkansas, Quesenbury’s rendering of the Fayetteville Female Seminary was engraved and published. A sketch of the courthouse and grounds at Van Buren dated from this period, and it is highly likely that the woodcut cartoons that appeared in the Arkansas State Gazette and Democrat on July 23, 1853, were done by him. More substantial reward came when this loyal Whig was appointed the receiver of public moneys at Fayetteville in 1852.

In 1853, he started the South-West Independent newspaper. Neutral in politics, he nevertheless promised to “advance or lead in all the great improvements and questions of the day.” The same year, he built a home in Fayetteville that stood well into the twentieth century. He had to stop publication of his newspaper in 1857 because of health problems. His financial predicament was perilous was well, but in 1859, he assisted Superintendent of Indian Affairs Elias Rector in removing some of the Seminole from Florida to Indian Territory. Passing through Little Rock (Pulaski County) on his way home, Quesenbury was induced to begin writing a column for the Arkansas State Gazette on pioneer days. These letters continued into 1861.

In 1860, he took over the temporary management of the newly founded Arkansian in Fayetteville, its owner-editor, Elias Cornelius Boudinot, having gone to Little Rock to edit the True Democrat while its former editor, Richard Mentor Johnson, was making his ill-fated gubernatorial run. During the gubernatorial election of 1860, Quesenbury made woodcuts of the candidates with appropriate satirical comments. The cartoons were promptly reprinted by the Arkansas State Gazette in Little Rock and then by newspapers out of state.

Quesenbury opposed secession, but once the Civil War began, he joined Brigadier General Albert Pike in Indian Territory, serving as major in the commissary department. Pike’s career there was turbulent, and Quesenbury was one of the minor players in the first clashes between Pike and Major General Thomas C. Hindman over lines of authority. His poor health returned, and in 1864, now in Texas, he tendered his resignation. One of his sons, Walker (named in honor of David Walker), was killed in an accident at Fort Washita in 1862.

Quesenbury remained in Texas with his family after the war’s end but did write a number of letters to Arkansas newspapers. In 1869, he was briefly the editor of the Navasota Weekly Tablet. In 1875, financial disaster hit. Following the loss of his land and house, Arkansas friends took up a collection to pay his travel expenses, and the following year, he was back in Arkansas. Although many offers of newspaper jobs came in, he elected to teach art at Cane Hill College. He also returned to writing poetry. In 1876, he read a poem honoring Mexican War veterans; two years later, he gave the first of several public readings of Arkansas: A Poem (1879) to the Arkansas Press Association. He later published the poem in pamphlet form and gave readings in various towns in the state.

In 1880, he moved to Neosho, Missouri, with his family, where he lived opposite Congressman M. E. Benton. He continued to draw and reportedly was working on a portrait at the time of his death on August 31, 1888; his wife survived him, dying on March 4, 1894; both were buried at the Odd Fellows Cemetery in Neosho. The couple had ten children, but only four survived into adulthood.

Albert Pike, who knew him for half a century, praised both his landscapes and his caricatures but was most taken by his writing: “I do not know where he got his command of language. No man ever wrote me such letters, so quaint and forcible, so full of acute remarks and bold expressions of opinion, of exuberant mirthfulness and queer fancies and grave reflections and sagacious axioms, expressed in incomparable language.” Two of his lines lived long in Arkansas history: “Be not affronted by a jest: if a man throws salt at thee, it will not hurt thee unless thou hast sore places.” The other, the concluding line in Arkansas: A Poem, was: “GOD LOVES NOT HIM THAT LOVES NOT ARKANSAS.”

For additional information:

Benton, Lee David. “On the Border of Indian Territory: The Oklahoma Adventures of William Quesenbury.” Chronicles of Oklahoma 62 (Summer 1984): 134–155.

Blake, Beulah. “A Sketch of the Life of W. M. Quesenbury (Bill Cush), 1822–1888.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 4 (Winter 1944): 315–316.

Dougan, Michael B. Community Diaries; Arkansas Newspapering, 1819–2002. Little Rock: August House, 2003.

———. “William Quesenbury: Poet of Arkansas.” Publications of the Arkansas Philological Association 3 (Summer 1997): 1–7.

Griffith, Nancy Snell. “Buena Vista: The Controversy in Verse.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 60 (Spring 2000): 75–85.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Quesenbury Caricature

Quesenbury Caricature  Quesenbury House

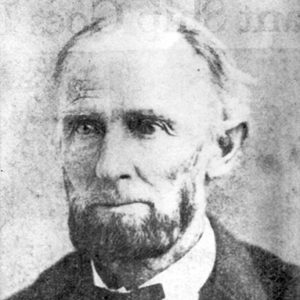

Quesenbury House  William Quesenbury

William Quesenbury  Van Buren Sketch by William Minor Quesenbury

Van Buren Sketch by William Minor Quesenbury

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.