calsfoundation@cals.org

More than Information: The Limits of AI

As I type these words, there is a button for the Microsoft Copilot, the company’s AI “assistant,” lurking in the bottom right-hand corner of my screen—its rainbow color a bright contrast to everything else on my screen, just begging to be engaged.

Do you see it? Microsoft would be delighted for me to click on that and make some use of that feature, since they are spending so much money on so-called artificial intelligence.

These companies are inserting their AI “agents” and “assistants” into everything they can, trying to make acceptance of AI some kind of fait accompli when it remains anything but. I’ve complained about this before on this blog, explaining how it was impossible for a chatbot to do what we do here at the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas, but the problem only grows. Recently, I was asked to review a book manuscript for a major university press, and when I opened the pdf in Adobe, I immediately had a pop-up saying that this seemed to be a big file and did I want a summary of it all? No, I did not want a summary, because my goal was to highlight possible shortcomings that might not be recognizable in summary form.

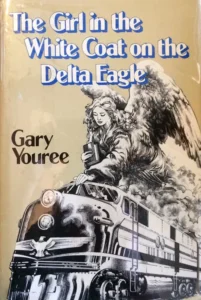

There is a sense among many terminally online people that fields like history and sociology and anthropology can be pretty much eliminated by simply feeding every published thing into an AI and letting it spit out whatever you want. Such a perspective assumes that most everything has already been digitized, when the reality is rather the opposite. When it comes to the National Archives and Records Administration, for example, some four percent of its holdings have been digitized, and the numbers sink further once you delve into state and local records. And this is for a first-world country, too. This is why genuine archival research still remains necessary even for those future historians studying today. Not everything is digitized and online. And everything that remains undigitized is not necessarily older. For example, the 1979 novel The Girl in the White Coat on the Delta Eagle was published by a major publisher, W. W. Norton, but is not new enough to have been born digital with an ebook available, and neither is it old enough to exist in the public domain and thus have been digitized as part of a project of putting public domain materials online.

There is a sense among many terminally online people that fields like history and sociology and anthropology can be pretty much eliminated by simply feeding every published thing into an AI and letting it spit out whatever you want. Such a perspective assumes that most everything has already been digitized, when the reality is rather the opposite. When it comes to the National Archives and Records Administration, for example, some four percent of its holdings have been digitized, and the numbers sink further once you delve into state and local records. And this is for a first-world country, too. This is why genuine archival research still remains necessary even for those future historians studying today. Not everything is digitized and online. And everything that remains undigitized is not necessarily older. For example, the 1979 novel The Girl in the White Coat on the Delta Eagle was published by a major publisher, W. W. Norton, but is not new enough to have been born digital with an ebook available, and neither is it old enough to exist in the public domain and thus have been digitized as part of a project of putting public domain materials online.

But it’s not simply the fact that AIs don’t have access to everything published thus far. There also arises a problem from materials that have been published. I started my own scholarly career looking at cases of racial violence in Arkansas. A historian looking at these cases learns to recognize a number of tropes common to lynching reports, such as the demonization of lynching victims or the alleged orderliness of lynch mobs. By “demonization,” I mean that people like John Hogan, lynched in 1875, were literally described as demons.

Imagine that you can feed AI all the documentation that exists. According to Emily M. Bender and Alex Hanna, authors of The AI Con, these programs are little more than glorified autocompletes, their robustness dependent upon the wealth of information from which they draw their inferences. So despite the fact that present-day historians are capable of recognizing certain tropes present in past reports of racial atrocities, the published work of those historians, for these AI programs, exists upon the same plane as the primary records themselves. And since the primary records outweigh, in number, the countervailing view of later historians, any AI drawing from a wealth of digitized newspapers would probably reproduce the racist paradigms of those earlier days. John Hogan was a demon. Those “Negroes” want to rape white women. Statistically, that would be what a large language model would spit out, because it is incapable of weighing the value of one source against another. It just takes the average and autocompletes the most likely conclusion based upon statistics.

Aside from the likely racist or sexist conclusions of some AI, consider something like Arkansas’s reputation in the world at large. Would you be fine accepting an AI-generated summary of the characteristics of Arkansas and Arkansans based upon the program’s own statistical survey of published materials? How often has Arkansas been derided in the media world at large, and how much might that accord or discord with your own experience? (Not to mention the fact that, as writer John Scalzi points out, AI is “a dedicated fact-failing machine.”)

AI can process information, but it can’t process “exformation.” This is a concept introduced by the Danish science writer Tor Nørretraders in his 1998 book, The User Illusion: Cutting Consciousness Down to Size. Information is what is communicated, but exformation is everything that is discarded to make communication possible. If I want to communicate the role an older male mentor played in my life, I start to think about his kindness, his firmness, and any number of other characteristics, and I might say to you, “He was like a father to me.” I discarded a number of adjectives and concepts in the process of describing him using the analogy of fatherhood. Everything discarded in the process is exformation. It’s like the bits of marble chipped away that make Michelangelo’s David what it is. Were those not discarded, we’d just be looking at a lump of rock.

In my own research on racial cleansing in Arkansas, for example, I read any number of books on ethnic cleansing and genocide and the like that I never cited. I never cited the Philip K. Dick novels I was reading at the time and how they informed my worldview, namely by giving me a sense of how people could exist without seeing reality as it was. A wealth of material has gone into producing books that just don’t evince their own influences. More was discarded than you will ever know to reveal what stands visible to all.

Information is not everything. There is more to our reality than just information. That means that there is more to us, collectively and individually, than can be encompassed by any AI dependent upon information to draw its inferences. We are more than information. We are more than what can be known.

By Guy Lancaster, editor of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas