Entry Type: Event

Hot Springs Shootout

aka: Hot Springs Gunfight

aka: Gunfight at Hot Springs

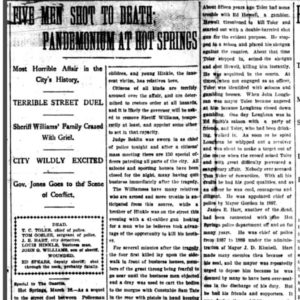

Hot Springs Shootout Article

Hot Springs Shootout Article

Hot Springs Smallpox Outbreak of 1895

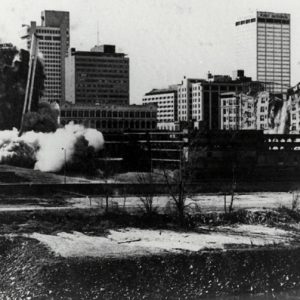

Hotels Imploded

Hotels Imploded

Houpts

Houpts

Housley v. State

Howard County Race Riot of 1883

aka: Hempstead County Race Riot of 1883

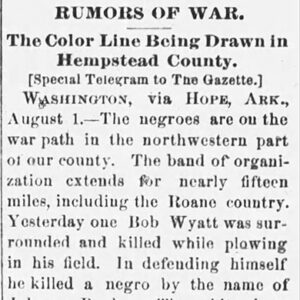

Howard County Race Riot Article

Howard County Race Riot Article

Howard County Reported Lynching of 1894

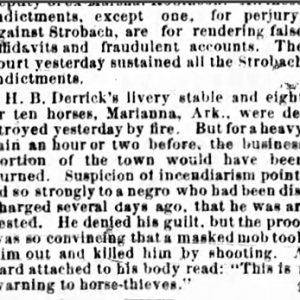

Jesse Howard Lynching Article

Jesse Howard Lynching Article

Howard, Jesse (Lynching of)

Hoxie Depot

Hoxie Depot

Hoxie Schools, Desegregation of

Huey, Cal (Execution of)

Hughes Flood

Hughes Flood

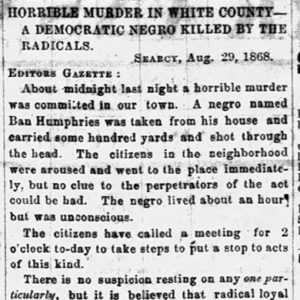

Ban Humphries Murder Letter

Ban Humphries Murder Letter

Humphries, Ban, and Albert H. Parker (Murders of)

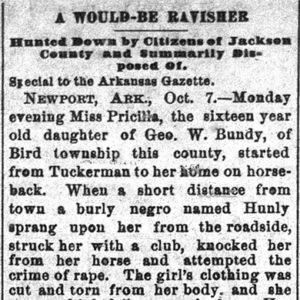

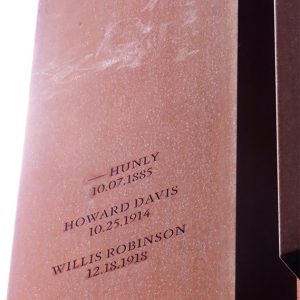

Hunley, Dan (Lynching of)

Hunley Lynching Article

Hunley Lynching Article

Hunter-Dunbar Expedition

aka: Dunbar-Hunter Expedition

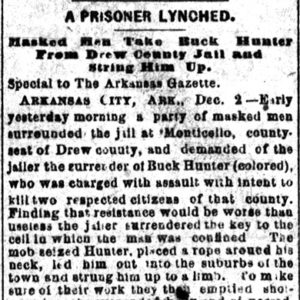

Hunter, Buck (Lynching of)

Buck Hunter Lynching Article

Buck Hunter Lynching Article

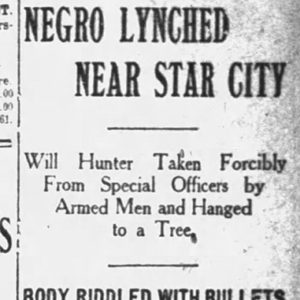

Hunter, William (Lynching of)

William Hunter Lynching Article

William Hunter Lynching Article

Huntersville and Clinton, Scouts from

Huntersville, Skirmish at

Huntsville Massacre

Hurricane Creek, Skirmish at

aka: Skirmish at Hunter's Crossing

Hurricane Katrina/Rita Evacuees

Asa Hutchinson at CSA Arrest

Asa Hutchinson at CSA Arrest

I-40 Dedication

I-40 Dedication

Impson, McClish (Execution of)

Independence County Fair

Independence County Fair

Indian Removal

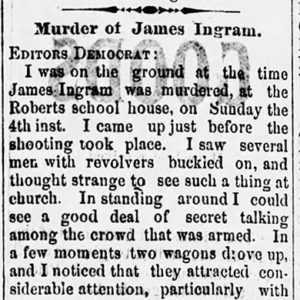

James Ingram Murder Article

James Ingram Murder Article

Ives, Kevin, and Don Henry (Murder of)

Izard County Tornado of 1883

J. S. McCune [Steamboat]

aka: Brilliant (Steamboat)

aka: USS Brilliant (Tinclad Gunboat)

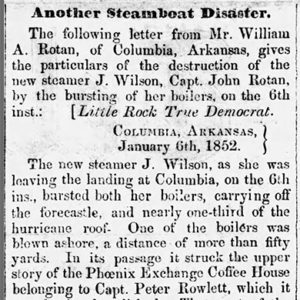

J. Wilson Steamboat Article

J. Wilson Steamboat Article

Jackson County Lynching

Jackson County Lynching

Jackson v. Hobbs

Jackson, Boge (Execution of)

Jackson, Goodwin (Execution of)

Jackson, Henry (Lynching of)

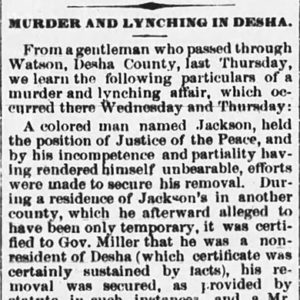

Henry Jackson Lynching Article

Henry Jackson Lynching Article