calsfoundation@cals.org

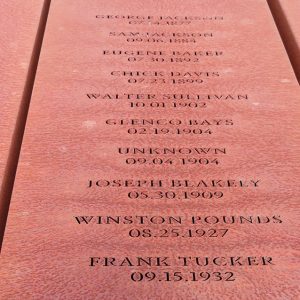

Winston Pounds (Lynching of)

Winston Pounds, accused of breaking into a white man’s house and assaulting his wife, was hanged by a mob near Wilmot (Ashley County) on August 25, 1927.

Census records indicate that Winston Pounds Jr., born around 1906, was the son of farmer Winston Pounds and his wife, Florence Pounds.

As sometimes happens, published accounts of the lynching vary significantly, especially between white-owned and African-American-owned newspapers. According to the Arkansas Gazette, Pounds, described as a “Negro farmhand,” entered the J. W. McGarry home while he and his wife were sleeping and assaulted Mrs. McGarry. She screamed, and he fled. Some accounts say that J. W. McGarry was actually in Little Rock (Pulaski County), and that Mrs. McGarry’s sister was staying with her while he was away. She alerted the neighbors following the assault.

Authorities used bloodhounds to track the alleged perpetrator and were led to Pounds’s home. He was arrested there at 2:00 p.m. on August 25, and supposedly confessed, saying he planned to attack “the first white woman [he] found.” Sheriff John C. Riley took Pounds into Wilmot and left him unattended in his car while “discussing with his deputies and several business men plans for getting Pounds out of town to avert mob violence.” Several men jumped into the car and drove out of town, followed by several other cars full of men. Once Sheriff Riley learned of the abduction, he reportedly attempted to follow but could not discern where the mob had gone.

Pounds was hanged from a tree limb, and the perpetrators supposedly left before he died. The body was still hanging from the tree late that night, and an inquest was planned for the following day: “Although the lynching created considerable excitement in Wilmot, the streets practically were deserted by 10 tonight. No further trouble is expected.”

On August 26, R. C. Wells, a member of the coroner’s jury, cut down the body. Justice W. N. Wilhite held an inquest, at which no witnesses were called. Even Sheriff Riley failed to appear. Circuit Judge Turner Butler said he had received no formal notice of the lynching and had no plans to call for an investigation. In absence of Sheriff Riley, his deputies “said they presumed that an investigation would be made and evidence presented to the next session of the Grand Jury in February regarding the lynching and the leaders of the mob. The deputies said, however, that Sheriff Riley had not consulted them.” One of the sheriff’s deputies said that he did not hear Pounds say anything about attacking any white woman he found, and that Pounds had not confessed in his presence. He added, however, that he was not with Riley and Pounds the whole time. He also stated that he was unable to recognize any members of the lynch mob. The verdict was that Pounds had died at the hands of persons unknown.

The Indianapolis Recorder, a weekly black newspaper, recounted many similar facts about the incident. Its report asserted, however, that Pounds’s father had bested J. W. McGarry’s father in an altercation several years before. The speculation was that the younger McGarry had been holding a grudge and planning retribution. Pounds was described as “a good young man, who was never known to be in any kind of trouble with anyone.” The information provided by the bloodhound was the only evidence “either sought or found” to prove that Pounds had attempted to assault Mrs. McGarry. According to the Recorder, Pounds was also tortured during the course of the lynching: “He was raised several feet from the ground, and acid was poured into his eyes and mouth. Pounds’ lower abdomen was stuck full of holes with knives and the body was left hanging to the tree.”

For additional information:

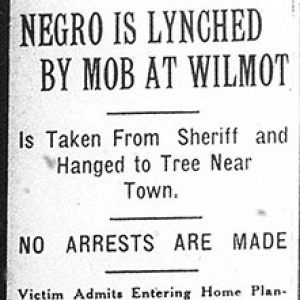

“Negro is Lynched by Mob at Wilmot.” Arkansas Gazette, August 26, 1927, p. 1.

“No Arrests for Wilmot Lynching.” Arkansas Gazette, August 27, 1927, p. 5.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Clinton, South Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Ashley County Lynching

Ashley County Lynching  Pounds Lynching Article

Pounds Lynching Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.