calsfoundation@cals.org

Washington County Lynching of 1856

aka: Randall (Execution of)

A mob of white citizens lynched two enslaved Black men, Aaron and Anthony, outside the city limits of Fayetteville (Washington County) on July 7, 1856. Racial terror lynching was a reality across the state, including northwestern Arkansas, during the antebellum period.

On the night of May 29, 1856, according to hearsay evidence, Aaron and Anthony attempted to rob and then attacked their enslaver, James Boone, at the door of his home in Richland Township. A third Black man, Randall, enslaved by Peter Mankins and the minor children of David Wilson Williams, was also reported to be involved. By the next morning, enslaved housekeepers were said to have found Boone injured near the entry of his home.

Despite the lack of witnesses, Randall, Aaron, and Anthony were named as the culprits responsible for the attack on Boone and held captive in an upper room in the Boone home while Boone lay unconscious for thirteen days. They were incarcerated in the county jail following Boone’s death on June 11.

Felix Batson, presiding judge of the Fourth Judicial Circuit of Arkansas, called a special session of the Washington County Circuit Court for the purpose of trying Randall, Aaron, and Anthony. Court commenced on June 30. A grand jury was seated the following day. In the absence of the Fourth Judicial Circuit’s prosecuting attorney, Hugh F. Thomason, Batson named in his stead Jonas M. Tebbetts, a Fayetteville resident and prosecuting attorney for the Seventh Circuit Court. Batson made the appointment despite a conflict of interest for Tebbetts, who was also the law partner of one of Boone’s sons. Batson appointed local lawyers Peter Pinckney Van Hoose and Elias C. Boudinot as defense counsel.

Including the grand jury, forty white males served as jurists throughout the proceedings. Court records did not include a verbatim transcript, but a later court record indicated that seventeen individuals, mostly from Richland Township, testified in the trial. Twelve white men, one white woman, two enslaved Black men, and two enslaved Black women received pay for their appearance in court.

Randall, Aaron, and Anthony were indicted for murder by the grand jury on July 1. The three men were tried separately. Randall’s trial began on July 2, following the indictment. On July 3, Randall heard the jury declare him guilty. On July 5, Aaron saw Tebbetts dismiss the case against him for lack of evidence. The same day, the jury in Anthony’s case acquitted him of all charges. On July 7, Randall contested his guilty verdict, but Batson refused his request for another trial and sentenced him to be hanged by the state on August 1, 1856. Court adjourned following the sentencing.

An anonymous source gave an account of the subsequent events of July 7 to the Fort Smith Herald newspaper that was published July 12, 1856. According to “the gentleman who recently returned from Fayetteville,” white Richland Township neighbors and the sons of Boone met at the courthouse and passed resolutions. Judge Batson and the grand jury foreman, Thomas Wilson, among others not named endeavored unsuccessfully to dissuade the mob from their deadly purpose. Randall remained in the jail, but this white mob led by the sons of Boone seized Aaron and Anthony and hanged them from a tree somewhere between the jail and Richland Township.

Born in Rowan County, North Carolina, James Monroe Boone (1788–1856) and his wife, Sophronia Smith Boone (1808–1835), migrated from Tennessee to Arkansas Territory around 1830. In 1856, Boone was a widower, a wealthy landowner, a top slaveholder in Washington County, and father of four adult sons: Daniel Thales (1826–1910), Benjamin Franklin (1828–1863), Euler Bernoulli (1831–1860), and Lafayette (1834–1900). All four of Boone’s sons were likely part of the lynch mob on July 7. Published accounts have attributed the act of hanging Aaron and Anthony to Benjamin and Lafayette. Both were educated as lawyers; Benjamin was the law partner of Jonas Tebbetts.

Although archived documents of enslavement effectively concealed the stories of enslaved persons’ lives as they would have told them, they occasionally did provide certain clues about the enslaved individuals, their families, and communities. No such document was recorded, however, that might have provided the ages or life circumstances of Aaron and Anthony. Randall appeared in three documents filed in Washington County between 1841 and 1857, the last showing his age posthumously as twenty-seven. Accordingly, Randall would have been between twenty-five and twenty-six years old in 1856, the Williams family having exacted his labor for at least fifteen years.

Boone descendants have been the primary sources of published narratives of Boone’s death, the trial, and the lynching that differ only in certain details. An alternative version, however, has survived through oral transmission and was documented by Melba Smith, a descendant of Fanny, a young Black woman enslaved first by James Boone. In this version, an unidentified enslaved Black woman was said to have dealt a blow with an axe to Boone’s forehead while he was in her living quarters. The three men are not mentioned.

The July 12 Fort Smith Herald newspaper article disavowed mob law but then refused to issue an opinion on the occurrence. However, the opinion of Washington County voters was clearly expressed when a few weeks after the lynching, they elected Benjamin Boone as one of the county’s representatives to the 1856 Arkansas General Assembly. Lafayette continued his practice of law in the county. Daniel prospered as a farmer in Richland Township, as did Euler as a lawyer in southern Missouri. Neither they nor any of the neighbors and Boone kinfolk from the Richland Township area who participated in the mob lynching suffered any known consequences. The remaining enslaved members of the James Boone estate were dispersed by sale to others or by inheritance to the Boone sons.

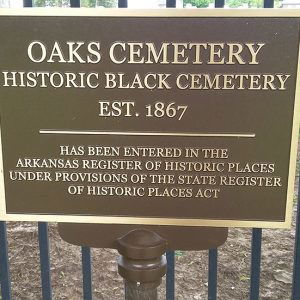

On May 15, 2021, a marker commemorating this act of racial terrorism was installed at historic Oaks Cemetery. The marker was a joint project of the Washington County Community Remembrance Project and the Equal Justice Initiative of Montgomery, Alabama.

For additional information:

Elliott, RoAnne, and Valandra. “Re-Presenting Aaron, Anthony, and Randall: Victims of Racial Terror Lynching in Washington County.” Flashback 70 (Winter 2020): 164–173.

Gearhart, Gretchen “The Murder of James Boone.” Flashback 56 (Autumn 2006): 159–166.

Jones, Kelly Houston. “‘Doubtless Guilty’: Lynching and Slaves in Antebellum Arkansas.” In Bullets and Fire: Lynching and Authority in Arkansas, 1840–1950, edited by Guy Lancaster. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018.

Lamy, Obed. “Racial Terror Lynching in Northwest Arkansas: Recounting the Story of Three Enslaved Males Lynched in 1856 – Documentary.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2021. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/4104/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Williams, Oscar E. “Trial of Three Slaves for the Murder of Doctor James Boone.” Flashback 10 (April 1960): 7–13.

Margaret Ann Holcomb

Fayetteville, Arkansas

Oaks Cemetery Plaque

Oaks Cemetery Plaque

James Monroe Boone is my great-great-grandfather on my father’s side and ever since I first found out about his history, I’ve been totally amazed by it. I’ve been told by my father that we were related to the Boone family but never did I know anything about this story until I one day did a little searching and found out about it. Now I’ve been planning to go to Washington County and find out even more, but to tell you the truth it’s kind of a black eye on my father’s family tree but still a little fascinating.