calsfoundation@cals.org

Tom Slaughter (1896–1921)

Dead before his twenty-fifth birthday, Tom Slaughter was a violent, arrogant, and handsome conman, bank robber, and killer. When he died on December 9, 1921, in Benton (Saline County), Slaughter had been given the death sentence for murder.

Tom Slaughter was born in Bernice, Louisiana, on December 25, 1896, but he lived in the Dallas, Texas, area until he was fourteen. Slaughter then moved to Pope County, Arkansas, where he was convicted of stealing a calf in 1911. Slaughter was sentenced to the Arkansas Boys’ Industrial Home. A few months later, he escaped. He returned to Russellville (Pope County), where he paraded before Sheriff Oates, who arrested him. He escaped from jail the second night. For the next ten years, Slaughter broke out of jails in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Arkansas.

In 1916, Slaughter was arrested for stealing automobiles in Dallas, Texas. He escaped from the Dallas County jail, “one of the…most strongly built in the Southwest, liberating seven other prisoners,” according to the December 10, 1921, Arkansas Gazette. Sentenced to six years in the Texas penitentiary, he escaped in July 1917, knocking out a guard with a shovel.

Slaughter formed a gang and terrorized the region, robbing banks in Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, Kansas, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania. In 1918, Slaughter was being returned to the Texas penitentiary. Inside the prison, he took a “pin and pricked hundreds of holes in his face and body, covered them with croton oil, which brought out a rash, ate two cakes of soap to bring about a fever and reported to the sick bay.” Hospital officials diagnosed smallpox and isolated him. Once again, he escaped.

In 1919, the Slaughter gang stole $24,000 in a noon bank robbery in Petty, Texas. Later, Slaughter and Fulton Green, a member of his gang, killed a bank cashier in Pennsylvania. Slaughter enjoyed theatrics. In September 1920, he and his gang robbed a bank in Graham, Texas, on a Saturday afternoon when the town was filled with citizens. In October, Slaughter, accompanied by four men and two women, arrived in Hot Springs, where the group went on a drinking spree, disturbing the peace. Hot Springs police went to investigate, a gunfight followed, and Slaughter and Green killed Sheriff Rowe Brown and wounded officer Bill Wilson.

Slaughter fled to Oklahoma, formed a gang, and continued robbing banks. Eventually, Slaughter was caught in Kansas and returned to Arkansas, though Arkansas officials had to bribe a Kansas sheriff before extradition could begin. Citizens in Hot Springs had offered a reward of $5,000 for the capture of Slaughter and Green.

Officials at Slaughter’s trial were fearful. A prison trusty claimed he had been approached about wrecking a passenger train behind the prison walls to distract officials while Slaughter escaped. While living at “The Walls,” as the prison was called, in Little Rock (Pulaski County), Slaughter asked for a minister to visit him. The Reverend W. B. Hogg of Winfield Memorial Methodist Church responded. Slaughter was converted and baptized into the church by Rev. Hogg, who became an advocate for Slaughter. Laura Conner, the only female member of the penitentiary board, also became an advocate for Slaughter.

In January 1921, Slaughter was sent to Tucker Prison Farm, where Warden Dee Horton tried to break Slaughter, who irritated him with his swaggering independence. The tall and handsome Slaughter had a reputation as a ladies’ man, and three women—Myrtle Slaughter of El Dorado (Union County); Nora Brooks of Ponca City, Oklahoma; and Mable Slaughter of Joplin, Missouri—claimed to be his wife. Warden Horton enjoyed whipping and intimidating one of his most illustrious inmates.

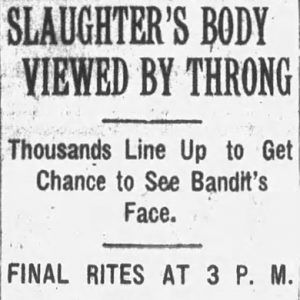

On September 18, 1921, Slaughter, attempting to escape, killed inmate Bliss Atkinson (who was in prison for his role in the Cleburne County Draft War). He was tried in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) for the killing and sentenced to die. Slaughter was transported to Little Rock and guarded around the clock. One week before his scheduled execution, Slaughter feigned illness, overpowered two guards, unlocked the stockade, and invited everyone who wished to make a break. Slaughter marched the nurse ahead of himself and walked to Warden E. H. Dempsey’s apartment, where he took the warden and his family as prisoners. For five hours, Slaughter paraded around the prisoners he had “freed,” taking the convicts’ money and valuables. Then, Slaughter left the prison with Jack Howard and five prisoners in Dempsey’s automobile. The police at Benton set up a road block. The prisoners abandoned the automobile and camped in the woods. Jack Howard, an inmate from Garland County, shot Slaughter three times, killing him. (Howard later claimed he had escaped with Slaughter to assist in Slaughter’s capture.) Slaughter’s body was taken to Benton, where “thousands stormed the Healey and Roth funeral home.”

The Arkansas Gazette on December 13, 1921, reported that the crowds were so large that the funeral home placed Slaughter’s body outside and allowed the curious to view him. The Palez Floral Shop of Benton received “several very expensive” orders from Hot Springs and all over Oklahoma. Three ministers, including Rev. Hogg, officiated at the funeral, and the crowd was estimated at more than 5,000.

For additional information:

Selph, Bernes K. “Escape from Prison.” Arkansas Democrat Sunday Magazine. February 19, 1961, p. 4.

Storey, Celia. “Beyond the Grave.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 27, 2021, pp. 1D, 6D. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/dec/27/beyond-the-grave/ (accessed April 11, 2022).

———. “Slaughter’s Story.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 13, 2021, pp. 1D, 6D. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/dec/13/slaughters-story/ (accessed April 11, 2022).

———. “A Turn for the Worse.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 20, 2021, pp. 1D, 6D. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/dec/20/a-turn-for-the-worse/ (accessed April 11, 2022).

Williams, Nancy A., ed. Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Wirges, Joe. “The Battle at Tucker Bathhouse Was Bloody.” Arkansas Gazette. February 22, 1953, p. 3F.

———. “Most Daring, Colorful of Them All.” Arkansas Gazette. February 15, 1953, p. 2F.

———. “The Night Tom Slaughter Captured the Wall.” Arkansas Gazette. March 1, 1953, p. 2F.

Jerry D. Gibbens

Williams Baptist College

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Tom Slaughter

Tom Slaughter  Tom Slaughter Death Article

Tom Slaughter Death Article

My father-in-law, Carl R. Leech, lived in Kentucky Community in Saline County at the time of Tom Slaughters death. Sheriff Jehu Crow called Leechs step-father to gather a posse because Tom Slaughter was coming their way. Leechs step-father told the children to turn off the lights and go to bed. Leech watched through the window as the gang went in front of the house during the dark of that night.

The next morning, the driver of the truck bringing Slaughters body to Benton Furniture Company and Funeral Home asked the young Leech if he would like to see Tom Slaughter. Leech replied affirmatively, and the driver pulled back the tarp and showed him Tom Slaughters body.

There is another story that says a friend of Leechs broke the window of the funeral home while looking through it at the deceased Tom Slaughter. There are also bullet holes remaining in the brick of Benton buildings made by the gunfight as the former prisoners fought their way past Saline County officers of the law.

Carl Leech shared this story with me many times before his death in 1988.