calsfoundation@cals.org

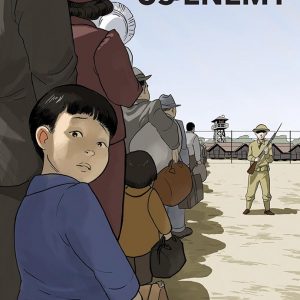

They Called Us Enemy

The graphic novel They Called Us Enemy, written by George Takei with co-authors Justin Eisinger and Steven Scott, and featuring black-and-white art by Harmony Becker, was published in paperback in 2019 by Top Shelf Productions; an expanded hardcover edition with a new afterword and other materials was published in 2020. Takei’s graphic memoir was named an American Library Association Notable Children’s Book for Older Readers and won the Will Eisner Award for Best Reality-Based Work. When he was a child, Takei and his family were brought to Arkansas and held in Rohwer Relocation Center in Rohwer (Desha County).

The story moves between the adult George Takei of Star Trek and internet fame and the child who was one of about 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent incarcerated during World War II. A traumatic scene that the adult Takei says is burned into his memory opens the book: George and his brother Henry are asleep in bed, harshly woken by their panicked father, who has to get the family, which includes the boys’ mother and baby sister, ready to leave their home. Soldiers with bayonets are at the door saying that the family has to evacuate their home under Executive Order 9006, which was issued less than three months after the Empire of Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

The book then shows Takei on a TED Talk stage, taking a trip back in time to the beginning of his family’s story, with his parents meeting in Los Angeles in 1935 and establishing a life there together. A cozy living room scene of decorating for Christmas is interrupted by news on the radio of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Soon, the nation is at war and anyone who looks like the enemy becomes the target of suspicion. “No Japs” signs appear, and eventually the U.S. government issues its own version of those signs, with an executive order “excluding” those of Japanese descent from the “military area” of the West Coast of the United States, to be held in one of ten incarceration camps throughout the country—two of which were in southeastern Arkansas: Rohwer and Jerome. Before they left, Japanese Americans had to part with their homes, their possessions, their cars—anything they couldn’t carry with them; many former neighbors took advantage of the situation by offering tiny amounts for valuable goods and seizing property and farms.

The Takei family first is taken to the horse stables at the Santa Anita Racetrack to be held temporarily; this is exciting for George and Henry but humiliating for their parents. A train to Arkansas follows, for what George’s father said was a vacation, trying to make the best of the situation for his sons, who were excited to be on the train despite the crowding and illness all around them. The adult Takei struggles with the darker side of his memories of this “joyful time of games, play, and discoveries,” saying, “I know that I will always be haunted by the larger, vaguely remembered reality of the circumstances surrounding my childhood.”

The family soon arrives at Rohwer, which would hold close to 8,500 people at its peak. They settle into their barracks, helped a bit by their mother’s smuggled-in sewing machine, which she uses to make curtains and rugs. Life is hard in Rohwer, with muddy ground, unfamiliar food in the large dining hall, and group bathrooms. And the kids have their own stressors, with older boys telling them that dinosaurs are outside the barbed-wire fences and starting games of “war” in which the Takei boys have to be the Japanese enemy of the older boys, who declare themselves “the Americans.” They also trick George into shouting what turns out to sound like a curse word to the guards in the tower, who respond by throwing rocks at him.

In the winter, the children see snow for the first time and celebrate their first Christmas at Rohwer, complete with a Santa, although George knows it is not the “real Santa” because this Santa is Japanese. But he keeps that knowledge to himself for his siblings’ sake. Winter also brings new hardships as George’s parents have to decide how they will answer the impossible and loaded questions on the loyalty questionnaire issued by the U.S. government. Because of his parents’ “no-no” answers to these questions, the family is sent in May 1944 to a higher-security facility in Tule Lake, California. Conditions are terrible and the unrest among the incarcerated people is traumatic for George’s parents, but there is one upside: George, the future actor, discovers the magic of film during the movie nights in the camp mess hall.

New challenges emerge as the war comes to an end: heartbreak over the fates of the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, where many in the camp had family members and friends, including George’s mother, whose parents lived in Nagasaki; confusion about whether it was best to remain in America or renounce American citizenship; and joy in the idea of returning “home” to Los Angeles coupled with apprehension about what they would be returning to.

As George grows into a teenager and studies history and civics, he is dismayed to find that the story of his past is not there: “I couldn’t reconcile what I read in civics books about the shining ideals of our democracy with what I knew to be my childhood imprisonment.” He begins asking his father questions about the family’s incarceration, filling in the details and gaps in his childhood memories. Enrolling at UCLA, George begins studying theater and performs in Fly Blackbird, a musical that “shined a light on the political and social injustices of the time.” Meeting Dr. Martin Luther King backstage helped solidify Takei’s call to social activism in the face of injustice. Getting the coveted role of Lieutenant Sulu on the Star Trek TV series was a dream come true for Takei, but, as he says, “most importantly, my unexpected notoriety has allowed me a platform from which to address many social causes that need attention”—including LGBTQ rights. And he used his fame to teach the American public about the troubling history of locking up perceived enemies and denying their rights as humans and Americans—a history that has repeated itself several times since George spent his childhood behind barbed wire.

The book ends with an illustration of George Takei and his husband Brad Takei standing together in the cemetery at Rohwer, with its monument to Japanese American soldiers who fought for, not against, America.

For additional information:

Lehocsky, Etelka. “George Takei Recalls Time in an American Internment Camp in ‘They Called Us Enemy.’” NPR, July 17, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/07/17/742558996/george-takei-recalls-time-in-an-american-internment-camp-in-they-called-us-enemy (accessed December 19, 2024).

Narayan, Niteeka. “Existentialist Textual Responses to the Japanese American Incarceration of World War II.” Honors thesis, Texas Christian University, 2025. Online at https://repository.tcu.edu/items/3ab81a74-3010-4db0-9afc-29fac6cb40eb (accessed June 6, 2025).

Rohwer Japanese American Relocation Center. http://rohwer.astate.edu/ (accessed December 19, 2024).

Takei, George, Justin Eisinger, and Steven Scott. They Called Us Enemy. Marietta, GA: Top Shelf Productions, 2019.

Welky, Ali. A Captive Audience: Voices of Japanese American Youth in World War II Arkansas. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2015.

Ali Welky

CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Literature and Authors

Literature and Authors George Takei

George Takei  George Takei

George Takei  They Called Us Enemy

They Called Us Enemy

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.