calsfoundation@cals.org

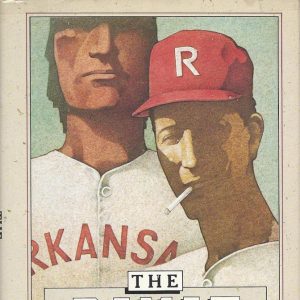

The Dixie Association

Donald S. “Skip” Hays, who was born in Florida and reared in western Arkansas, developed an early interest in literature and, after a vagabond career that included years of semiprofessional baseball, settled on writing and teaching. He turned out two ribald Southern novels, the more celebrated of which was The Dixie Association, published in 1984, about a wild band of misfits who made up a fictional professional baseball team at Little Rock (Pulaski County) in the late 1960s.

The Dixie Association is about Hog Durham’s single season as a professional ballplayer; he is furloughed early from an Oklahoma prison so that he can join the team. Hog then engages in endless maneuvers with his manager, “Lefty,” and a Little Rock trial lawyer to evade the clutches of sheriffs, prosecutors, his parole officer, and assorted con men so that he can stay out of a jail cell until the season ends—and thus perhaps help his team win the pennant. His teammates have similar personal ordeals and calamities arising from their past or current proclivities, like drinking and gambling. Hog’s team, the Arkansas Reds (not as in Redlegs or Redbirds, but as in Communists), is similarly engaged in a perpetual war with elements of the community—religionists, right-wingers, white supremacists, and civic leaders—that want the team to do badly, if not to disband.

The Reds are a ragtag band led by a one-armed Marxist manager (who also runs a food cooperative for poor people), and include a woman masquerading for the first few games as a man, two Cuban pals of Fidel Castro, a Black Muslim, a pitcher named Genghis Mohammad Jr., several farmers, two Cherokees, a Jew, and one white supremacist who finally abandons the team and joins its biggest competitor in the league, a team from Selma, Alabama—which, of course, is near the Edmund Pettus Bridge, scene of the famous police assault on civil rights marchers in the summer of 1965.

All the players and other lecherous and hard-drinking characters have crazy names or nicknames, often reminiscent of familiar Arkansas figures. A right-wing judge is not U.S. District Judge Oren Harris of El Dorado (Union County), but Oren Hawkins. The superhighway running by the baseball park is the Orval Faubus Expressway, instead of the Wilbur D. Mills Freeway (Interstate 630), which at the time of Hays’s writing ran by Ray Winder Field, the ballpark of the Arkansas Travelers, which served as the archetype of the Reds.

Although Skip Hays was never known to have robbed a liquor store or a country bank, like his protagonist and narrator in The Dixie Association, he and his fictional first-baseman Hog Durham shared one great experience, nearly a decade playing semiprofessional baseball—in Hog’s case for a squad of convicts in Oklahoma, in Hays’s case for real semiprofessional teams in Massachusetts and eastern Oklahoma, where The Dixie Association starts. Hays’s own eight years in the semipros gave the book its singular appeal to baseball addicts, as well as to the sizable number of devotees of the genre called “baseball books,” both nonfiction and fiction. His nearly pitch-by-pitch accounts of key games instruct readers in the arcane guiles of hitting, pitching, fielding, and strategizing, while entertaining them with a never-ending flow of profane metaphors and earthy dialogue. The novel was nominated in 1984 for the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction by the PEN/Faulkner Foundation.

The Dixie Association is as much a political or philosophical tract as it is an entertaining fiction, but the extremes of everything—the bizarre plots, the endless impish dialogue, the pompous zealots who often inhabit the stands or stand by the gate, and the crazy, corrupt owners and managers of opposing teams—bothered some literary critics, who considered it far too exorbitant. Hog’s own vast repertoire of metaphors spreads across every page. (Examples: “He struck Pick Mattox out on three spitters that came down like the law on a poor man” and “That damned Indian jumped like a ten-dollar whore at a hundred-dollar offer and knocked old Lamp out colder than a two-day turd.”) Kirkus Reviews’ critic tired of the mysterious subplots, all the cute names and metaphors, and the “unsubtle, undisciplined satire/comedy with dated counterculture attitudes strewn over the serial formlessness of a sports novel.”

The Dixie Association was published by Warner Books, Inc., and Louisiana State University Press reprinted it in 1997 as part of a series called Voices of the South. The Atlantic Monthly Press published Hays’s second novel, The Hangman’s Children, in 1989. In a review, the New York Times complained that Hays’s characters in this follow-up book “protest too much and sag under the weight of their metaphorical baggage.” Even Hays’s backwoods characters were “unnaturally articulate and talk far too much.”

While he was teaching creative writing at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County), Hays also wrote short stories, a number of which were collected in Dying Light and Other Stories, published in 2005 by MP Publishing Limited. He was awarded the Porter Prize, Arkansas’s premier literary award, in 2006.

For additional information:

Chappell, Charles, and Ashby Bland Crowder. “Donald Hays: A New Political Novelist.” Mississippi Quarterly 43 (Winter 1990): 59–68.

Mason, Deborah. “The Conscience of the Flimflam Man.” New York Times, National Edition, August 13, 1989, Section 7, p. 10.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Literature and Authors

Literature and Authors The Dixie Association

The Dixie Association

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.