calsfoundation@cals.org

Sultana

The Sultana steamboat disaster in 1865, at the end of the Civil War, has been called America’s worst maritime disaster. More people died in the sinking of the riverboat Sultana than on the Titanic. However, for a nation that had just emerged from war and was still reeling from the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, the estimated loss of up to 1,800 soldiers returning home on the Mississippi River was scarcely covered in the national news. The remains of the steamboat are believed to lie buried in Arkansas.

Those aboard the boat were mostly Union soldiers from Midwestern states such as Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana. Having been taken prisoners of war, they were sent to the notoriously overcrowded Confederate prisons of Cahaba in Alabama and Andersonville in Georgia. Those POWs who survived at war’s end in April of 1865 were marched to Vicksburg, Mississippi, for their return north.

When the survivors came in sight of the Mississippi River at Vicksburg, they shouted and sang with joy. The army was paying the Sultana’s captain—who was part-owner of the boat—five dollars for each enlisted man and ten dollars for each officer taken aboard. Those who boarded the side-wheeler found a boat built for 376 that took on, by some reports, almost 2,400 men, as well as some women and children who were in passenger cabins.

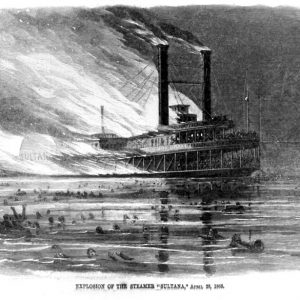

The Sultana left Vicksburg for Cairo, Illinois, forcing its way against the strong current of the Mississippi at flood stage. On April 27, 1865, at about 2:00 a.m., the Sultana was ten miles upriver from Memphis, Tennessee, with men sleeping on deck or anywhere they could find space when the straining boilers exploded, blowing the ship apart.

Men who had been sleeping suddenly found themselves immersed in the cold waters of the swollen river. Many were killed instantly by the explosion, fire, falling timbers, shrapnel, and searing steam from the boilers, as well as by drowning. Reports estimate the number of dead as high as 1,800, with hundreds of bodies floating in the river when Memphians awoke the next morning.

According to witnesses, it took about twenty minutes for the remains of the Sultana to burn to the waterline, finally resting in mud on the Arkansas side of the river. It is believed buried today under about twenty feet of soil beneath a soybean field in northeast Arkansas. In nearby Marion (Crittenden County), a historical marker pays tribute to the Sultana disaster.

Many of the dead were buried in Memphis cemeteries, while some who could be identified were taken home to places such as Ohio, where cemetery markers pay tribute. Survivors of the Sultana disaster formed a national association in the 1880s, and their descendants hold annual reunions on the anniversary of the tragedy.

In 2015, the Sultana Disaster Museum opened in Marion, two years after the Sultana Historical Preservation Society was incorporated. In 2019, the Arkansas General Assembly designated April 27 each year as Sultana Remembrance Day. In 2023, U.S. Senators John Boozman and Tom Cotton began advocating that the U.S. Mint create, as part of program commemorating historical events, a Sultana coin, with proceeds going to the Sultana Disaster Museum. The Sultana explosion is central to the plot of the 2024 novel When Hope Sank.

For additional information:

Baker, Elias John. “‘No Place in American History’: Remembering and Forgetting the Sultana Disaster.” PhD diss., University of Mississippi, 2021. Online at https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/2086/ (accessed October 18, 2022).

Berry, Chester D., ed. Loss of the Sultana and Reminiscences of Survivors. Voices of the Civil War. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2005.

Bryant, William O. Cahaba Prison and the Sultana Disaster. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1988.

Hamilton, Jon. “The Shipwreck that Led Confederate Veterans to Risk All for Union Lives.” National Public Radio, April 27, 2015. http://www.npr.org/2015/04/27/402515205/the-shipwreck-that-led-confederate-veterans-to-risk-all-for-union-lives (accessed December 7, 2020).

Heard, Kenneth. “Teacher Builds Replica of Historic Steamboat.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 5, 2015, pp. 1A, 8A.

Huffman, Alan. Sultana: Surviving the Civil War, Prison, and the Worst Maritime Disaster in American History. New York: Collins, 2009.

Kelly, David A., Jr. “Sultana: Victim of Courtenay’s Coal Torpedo?” Civil War Navy 6 (Fall 2018): 34–44.

Potter, Jerry O. The Sultana Tragedy: America’s Greatest Maritime Disaster. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, 1992.

Randall, Mark. “The Sultana: Civil War’s Titanic.” Jonesboro Sun, September 16, 2007, pp. 1C, 12C.

Salecker, Gene Eric. Disaster on the Mississippi: The Sultana Explosion, April 27, 1865. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996.

Sultana Association of Descendants and Friends. https://www.thesultanaassociation.com/ (accessed February 10, 2026).

Nancy Hendricks

Arkansas State University

My mother, the late Marion Sue Thompson, did the painting for the cover art of Jerry O. Potter’s The Sultana Tragedy. She was born and raised in Arkansas and passed away on 7/13/07.

Many of those boys also came from East Tennessee. They had been captured by Gen. Forrest near McMinnville, TN, and sent to Andersonville. They were hoping to get off the Ohio River where it branched off into the output of the Cumberland River, and then get as far as possible up into East Tennessee before they had to walk the rest of the way.

I am going down to the river today. It is at historically low levels. TV weathermen are calling for minus 11 and staying there till we get some rain. My great-grandfather, Cole Smith, fought for the Union and came home to a little town called Mitchell, IN. What a price those men must have paid to preserve their way of life. There would be no place to call home without their sacrifice.

Now Cole’s name will live on as long as there is an internet.