calsfoundation@cals.org

Sturgis Williford Holmes Jr. (1936–1992)

2009 April Fools' Day Entry (1/2)

Sturgis Williford Holmes Jr. was a famous Arkansas folk artist who specialized in the medium of paint-by-numbers. According to art historian Taylor Panini, Holmes’s output was larger than any other paint-by-numbers artist’s in the continental United States, though this claim remains controversial.

Sturgis Holmes was born on April 1, 1936, in rural Van Buren County to Sturgis Holmes Sr., an itinerant chicken farmer, and Bethejewel Haggis Holmes; he had eleven siblings. He possibly studied in Dennard (Van Buren County) schools, though there is no record of him ever graduating. The Holmes family was poor, and Holmes Sr. had to take up the illicit manufacture of spirits—i.e., moonshining—in order to make ends meet. As Holmes recounted to later interviewers, when his father was flush with cash, he would treat all the children to a present from the Sears catalogue, which, in 1950, included the first ever paint-by-numbers kit. Holmes soon developed a passion for the art form and took odd jobs in order to buy ever increasing numbers of kits. By 1956, when he was only twenty, he had successfully completed 131 paintings.

Holmes continued doing odd jobs throughout his life, never really settling in a profession and apparently never marrying. His sole concern seemed to be acquiring enough money for his paint-by-numbers kits, painting by numbers having grown into an obsession. Lacking storage space for his proliferating canvases, he often gave paintings to friends and neighbors. In the late 1960s, as the tourist economy of the Arkansas Ozarks was developing, he was convinced by a friend to offer his pieces for sale at Rex’s Bait Shop outside of Old Botkinburg (Van Buren County). His paintings proved popular among both the local crowd and people passing through, but it was not until the late 1980s that his work came to the attention of folklorists operating in the area. The last few years of his life saw him catapulted into the national spotlight as folklorists, anthropologists, art historians, and journalists traveled to his home to interview the rural master of paint-by-numbers.

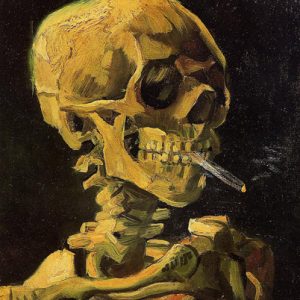

Holmes’s artistic influences—aside from the classical paintings reproduced in the kits he purchased—remain a mystery. In interviews, he admitted a disdain for the work of Vincent van Gogh—saying, “It’s hard to stay in the lines doing one of his”—and, when shown a painting by non-representational artist Piet Mondrian, exclaimed, “That wouldn’t be any kinda fun to do. That don’t look like nothing at all!” Also a mystery is the extent to which he intended his work to comment upon the modernization of the previously isolated hills in which he lived. Many researchers have attempted to analyze the subtext of his paintings, correlating the pattern of strokes, the thickness of his painting, or his choice of subject matter to social developments in the Ozark Mountains at the time, but no single interpretation of his work has been widely accepted by the academic community. These problems are only compounded by the fact that, as Holmes’s reputation has grown, people have been offering canvases for sale under his name, and this proliferation of nearly identical paintings all attributed to Holmes, with little record of provenance or authenticity, has only made a thorough study of his work more difficult to undertake. As historian Michael B. Dougan has written, “Gullible folklorists and art collectors, looking for rare paintings by Holmes, flooded the area buying up every paint-by-numbers piece they saw. At last count, there were, in museums and archives across the country, at least ninety-seven copies of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, all supposedly rendered by the masterful hand of Sturgis Williford Holmes Jr.”

Art historian Taylor Panini has labeled Holmes the “unparalleled master of the paint-by-numbers genre,” adding that the Arkansan’s continuing popularity in the art world is due to a “discourse of alterity that contravenes the usual revolutionary rhetoric of the art world. He understands that, in paint-by-numbers, there is a predestinate end, that the artist is essentially bound to a fate which he cannot escape, but rather than struggle against this, as we see in the corpus of Greek tragedy, he instead takes comfort in the ultimate end, knowing that any revolt against the system, any changing of colors with numbers, would only rob him of the picture he seeks to create. This discourse lay at the nexus of mass consumer culture and individual conscience.”

Holmes died on July 24, 1992, following a boating accident on the Middle Fork of the Little Red River. At the time of his death, he was rumored to have completed approximately 1,200 paintings, and an inventory of his trailer revealed more than a dozen uncompleted canvases. Many of his works can be viewed at the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History, the Walton Arts Center, and the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, though the largest collection is housed at the Crystal Bridges Museum of Art.

April Fools!

For additional information:

Dougan, Michael B. Taint by Numbers: Moral Degeneration in the Fine Arts Culture of the Arkansas Ozarks, 1950–1983. Harrison: North Arkansas College Press, 2001.

Panini, Taylor. Soooie Generis: Inside the Creative World of Sturgis Williford Holmes Jr. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

Debbie Perkins

University of Arkansas at Hogeye Museum of Fine Arts

Paint by Numbers

Paint by Numbers

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.