calsfoundation@cals.org

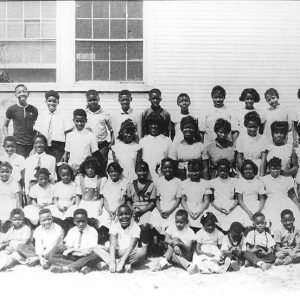

Rosenwald Schools

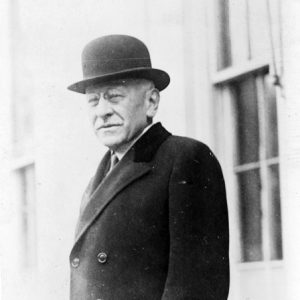

Julius Rosenwald was one of the most significant figures in Southern Black education. Although Rosenwald was a successful businessman, his philanthropic work has always overshadowed his financial success. His involvement in providing grants to build schools for African Americans across the South, including Arkansas, contributed greatly to the creation of better educational opportunities for Arkansas’s African American population.

Rosenwald was born on August 12, 1862, in Springfield, Illinois, to Jewish immigrant parents. He never finished high school or attended college but went into the clothing business instead. His philanthropy began with the support of Jewish immigrants, which surely came from his family’s heritage, and then expanded to include African Americans after he was influenced by Booker T. Washington’s autobiography, Up From Slavery. Rosenwald believed that a philanthropist should focus on expendable rather than endowment resources. He felt that donors needed to make sure that their contributions would make the most impact within their lifetimes. The needs and problems of future generations, he believed, should be left to the philanthropists of the future to solve.

After entering the clothing business in 1878, Rosenwald was able to gain the financial resources to carry out his philanthropy. He invested $35,000 in the stock of Sears, Roebuck, and Company in 1895, and in a little more than thirty years, it grew into $150,000,000. He became president of the company in 1908 and chairman in 1922. Rosenwald became a trustee of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in 1912 and made gifts to the rural school movement being carried out by the institute, primarily through close contact with his friend Booker T. Washington. Washington had a goal of providing safe, purpose-built school buildings for African Americans, something that many locations did not have, and Rosenwald wholeheartedly agreed with, and financially supported, Washington’s dream. The rural school building program would be administered by Tuskegee until 1920, when it was taken over by the Julius Rosenwald Fund.

However, Rosenwald did not exclusively support Tuskegee’s rural school building program. Rosenwald’s funds also made it possible to build twenty-five YMCA buildings and three YWCA buildings for African Americans after he initiated a challenge in 1910, whereby he would give $25,000 to any community that could raise $75,000 for a Black YMCA. This stimulated gifts from other philanthropists for similar projects in many Northern and Southern cities, including the financial support for the Rosenwald Apartments, a housing development that provided low-cost housing to African Americans in Chicago. Rosenwald was also active in a number of Jewish organizations, and he granted substantial financial support to the National Urban League. He was also appointed a member of the Council on National Defense and served as chairman of its committee on supplies.

In 1917, Rosenwald established the Julius Rosenwald Fund, which arguably attracted more money for the benefit of Black education than any previous philanthropic undertaking. The fund’s broad purpose was the betterment of mankind, but it was aimed more specifically at creating more equitable opportunities for African Americans in the South. Unlike many charitable organizations, the Rosenwald Fund would help a school only if the community had raised some of the money themselves. Rosenwald and the directors of his trust first directed their attention toward building rural schools, then toward high schools and colleges, and finally toward providing grants and fellowships to enable outstanding Black and white individuals to advance their careers. The directors of the trust were also involved in the direction of the curriculum at all levels of education, with their emphasis on the educational needs of rural children. The directors maintained that it was necessary to have vocational skills; math, reading, and writing skills; an understanding of biological processes and farming; and knowledge of the fundamentals of sanitation and health.

State records indicate that when the fund ceased sponsoring school building programs, it had aided in the building of 389 school buildings (schools, shops, and teachers’ homes) in forty-five counties in Arkansas. (A total of 4,977 schools, 217 teachers’ homes, and 163 shop buildings were built in fifteen states across the South with the assistance of more than $4.3 million from the Rosenwald Fund.) The fund contributed over $300,000 to Arkansas. The state or counties owned and maintained all of the schools, and the land was usually donated by a white landowner. Rosenwald (and Washington as well) believed very strongly in the local community playing a hands-on role in the development of the school. The local community was supposed to match the grant through cash, materials, or labor, so that the community would have a strong commitment to the program. In fact, many building campaigns were initiated by local African-American leaders, and the schools built represented the community’s determination to provide a decent education for its students

In Arkansas, R. C. Childress of Little Rock (Pulaski County) was the Rosenwald building agent during most of the time of the fund’s existence. (An earlier building agent, Percy L. Dorman of Pine Bluff’s Agricultural, Mechanical and Normal College—now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff—served from 1918 to 1922.) Childress was the first degree graduate of Philander Smith College and the second Black employee of the state Education Department. The responsibilities of the Rosenwald building agent were numerous and included helping the rural community to raise their share of the school’s cost, inspecting the new buildings, promoting good will between the races, and meeting with and influencing public school officials. Meeting with the local public school officials was critical in order to allow the Rosenwald Fund to be able to help in the construction of a modern school building. Although the grant for the Rosenwald Fund helped with the construction of the building, it was really the local community that provided the enthusiasm to see it through.

With Julius Rosenwald’s death on January 6, 1932, in Chicago, Illinois, the school building portion of the Rosenwald Fund stopped. However, the fund continued to fund other endeavors, notably a Fellowship program, until it closed. Rosenwald had required, in keeping with his beliefs that donors needed to make sure that their contributions would make the most impact within their lifetimes, that the fund spend all of its money within twenty-five years of his death. However, by 1948, nine years ahead of the required date, the fund had done so and had closed.

Most of the Rosenwald Schools in Arkansas were built in the southeastern half of the state, where there was a greater need for school facilities for Black students, but schools were built as far northwest as Franklin and Logan counties. To aid in the design and construction of the schools, Samuel Smith, general field agent for the Rosenwald Fund, developed a series of floor plans and specifications for a variety of schools, using the most up-to-date innovations in school design. The blueprints were published in a book titled Community School Plans and could be obtained from the Rosenwald Fund through the state’s education office. Smith felt that having a stock set of blueprints and specifications would allow any community to build a quality school without having to hire an architect, and the school plans turned out to be one of his greatest legacies. Although plans were provided, it was not necessary for schools to be built using the standard plans. Any non-standard plan used, however, had to be approved by the Rosenwald Fund.

In 2002, Rosenwald Schools gained national attention when the National Trust for Historic Preservation named all Rosenwald Schools one of America’s eleven most endangered places. A few years later, efforts spearheaded by the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program found that eighteen Rosenwald buildings of the original 389 remained in Arkansas. Today, a few of the buildings have been rehabilitated, such as the school in Selma (Drew County), now a community center, and some schools have active alumni associations. Some no longer exist; the Chicot County Training School in Dermott (Chicot County), for example, collapsed in 2020. However, most are vacant and deteriorating, lacking markers to indicate their important place in Arkansas’s history.

For additional information:

Deutsch, Stephanie. You Need a Schoolhouse: Booker T. Washington, Julius Rosenwald, and the Building of Schools for the Segregated South. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2011.

Embree, Edwin R., and Julia Waxman. Investment in People: The Story of the Julius Rosenwald Fund. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1949.

Hoffschwelle, Mary S. Preserving Rosenwald Schools. Washington DC: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 2003.

———. The Rosenwald Schools of the American South. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2006.

McNutt, Chelsea Deserea. “Arkansas’s Rosenwald Schools, 1917–1924.” MA thesis, Arkansas State University, 2018.

National Register of Historic Places nomination forms for various Rosenwald Schools. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Rosenwald School Initiative. https://savingplaces.org/places/rosenwald-schools (accessed October 20, 2025).

Porter, David. W. “A Brief History of the Julius Rosenwald Fund Building Program with Special Reference to Arkansas.” MA thesis, Fisk University, 1951.

Werner, Morris R. Julius Rosenwald: The Life of a Practical Humanitarian. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1939.

Whitworth, Katherine. “Vanishing Past: Arkansas’s Remaining Rosenwald Schools Are Eroding Monuments to Little-Known History.” Arkansas Life 3 (November 2010): 43–47.

Williams, Helaine R. “Legacy Lost.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, March 7, 2021, pp. 1E, 4E.

Wynn, Xavier Zinzeindolph. “The Development of African American Schools in Arkansas, 1868–1963: The Operation of Black and White Schools with Regards to Funding and the Quality of Education.” EdD diss., University of Mississippi, 1995.

Ralph S. Wilcox

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program

There is a new film on Julius Rosenwald: http://www.rosenwaldfilm.org/.The film is excellent and was shown as fundraiser here in Beaumont, Texas.