calsfoundation@cals.org

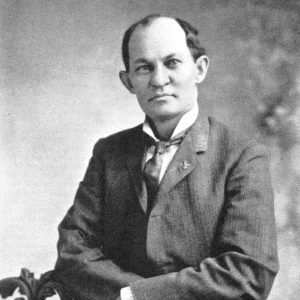

Robert Lee Rogers (1868–1935)

Robert Lee (Bob) Rogers served two years in the Arkansas General Assembly, eight years as a prosecuting attorney, and two years as Arkansas’s attorney general, initiating important antitrust suits against monopolistic corporations. He ran unsuccessfully for governor and then became one of the state’s outstanding criminal defense lawyers. He was also a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the recently revived Ku Klux Klan.

Bob Rogers was born on January 28, 1868, on a farm at West Point (White County), the oldest child of David E. Rogers and Maria Taylor Rogers. After his father died when he was about eleven, he dropped out of school to become the family’s principal breadwinner. He worked on nearby farms, and, after moving to Little Rock (Pulaski County), held many jobs, including hawking newspapers, working in a printer’s office and at Quapaw Cotton Mill, and working as a carpenter at the Iron Mountain railroad shop. At age eighteen, on November17, 1886, he married Laura Schwarz, and they eventually had two daughters. He attended night school when he could and began to study law by himself. Throughout his life, he relied on a natural talent for speaking in public.

Anyone in the frontier region of western Texas who was familiar with some basic law texts could apply to a district judge and, after a cursory oral examination, receive a license to practice law. By 1891, Rogers was one of three lawyers in Lubbock, Texas. He also served as the area’s county attorney and edited a short-lived newspaper, the Lubbock Leader.

After three years in Texas, he moved back to Arkansas, settling in Mulberry (Crawford County) to practice law and to pursue political office. In 1898, he was elected as one of the two state representatives to the Arkansas General Assembly from Crawford County.

In 1900, he moved his family and law practice to Van Buren (Crawford County) and twice won election as prosecuting attorney for the Fifteenth Judicial District, then consisting of Crawford, Franklin, and Logan counties. To prove he was a man of letters despite his uneven education, Rogers wrote a novel titled Tom Johnson, a melodrama recounting a young Texas lawyer’s story; it was published in 1904 by Tennyson Neely of New York.

In 1904, Rogers won election as Arkansas’s attorney general. He defeated the favorite in that race, Judge Jeremiah V. Borland, the friend and preferred candidate of Governor Jeff Davis, the dominant figure in state politics. The decisiveness of Rogers’s victory had made him the favorite in early speculation about the governor’s race in the upcoming Democratic Party primary of March 1906, and he soon declared he would enter that campaign. He hoped to follow the recent paths of Simon Hughes, James P. Clarke, and Davis, the state’s first politicians to vault from the attorney general’s office to the governor’s.

On many matters, Attorney General Rogers issued advisory opinions that produced little or no controversy, including those on road taxes, salaries of penitentiary officials, and uniform school texts. Rogers’s most important achievements as attorney general, however, were lawsuits to enforce Arkansas’s antitrust law of 1905. This popular measure was largely enacted on the initiative of Governor Davis, who had made antitrust central to his political career, promising to drive from the state all monopolistic corporations that exploited consumers, threatened economic freedoms, and corrupted politics. The governor, however, not only did not support Rogers’s antitrust litigation, but he impeded his efforts. Davis vetoed, for example, an additional position in the attorney general’s office, which would have helped antitrust prosecutions, and he found fault with almost everything that Rogers did. Overshadowing all else was a bitter political struggle over Rogers’s ambition to succeed Davis as governor.

Often, Rogers replied in kind to the governor’s opposition. Rogers sought to overturn funding for the Arkansas militia (National Guard), arguing it had not received a proper vote in the legislature and claiming its real purpose was to buy votes for Davis’s election in 1906 to the U.S. Senate, since Davis’s chief aide, Charles Jacobson, also served as the militia’s adjutant general. The Arkansas Supreme Court ruled against Rogers but not before he assaulted Jacobson in the governor’s office, slapping his face several times and inviting him to settle matters man to man. Rogers claimed Jacobson had made crude remarks about his family. Refusing to engage in fisticuffs, Jacobson nonetheless struck the last blow. Some twenty years later, in his memoir of Jeff Davis and his times, Jacobson asserted that 1905 antitrust law was a “dead letter” that led to no “bona fide” antitrust prosecutions, a claim mistakenly repeated long afterward in several histories of the progressive era of Arkansas politics that failed to credit Rogers’s antitrust victories.

The depth of hostility between Rogers and Davis was revealed early in the campaign season of 1905–1906. Davis, running for U.S. Senate, spent almost as much time in his race denouncing Rogers as he did his own opponent. In September 1905, Davis sought to amplify concerns about Rogers’s temperament to serve as governor, raised by the attack on Jacobson. Davis claimed that Rogers had threatened to kill him. Rogers replied in the same colorful language Davis often used, admitting that he might have threatened to “hurt” the governor if he slandered Rogers’s family but then continued: “Kill you? Why I can take a corncob with a lightning bug on the end of it and make you jump into the Arkansas River.” Nonetheless, Rogers lost his bid to become governor.

While running for governor, Rogers initiated several important antitrust prosecutions. He may have anticipated these actions would help his campaign, but the outcome of most litigation occurred well after the election was over. Besides, Davis was so identified with the antitrust issue that Rogers’s efforts had little effect on the race. Using the $5,000 the legislature appropriated to enforce the law, Rogers hired two lawyers to help with litigation, and by July 1905, Rogers achieved his first victory when the Arkansas Supreme Court in Hartford Fire Insurance v. State ruled favorably on the antitrust statute’s constitutionality and against the company. All major fire insurance firms subsequently withdrew from Arkansas to avoid litigation, imposing financial hardship on the state’s citizens and pressuring its leaders to retreat. Those companies returned to the state only after the 1907 legislature gave in and exempted fire insurance companies from antitrust law. Rogers’ greatest antitrust victory occurred after he left office when the case he had initiated, Hammond v. Arkansas, was successfully argued before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1909 by Lewis L. Rhoton, the court ruling in favor of Arkansas and its antitrust law.

Rogers also successfully secured financial settlements of antitrust cases against both the International Harvester Company and the Hammond Company, a meatpacking firm. The major meatpacking companies sold their Arkansas businesses to other out-of-state firms who agreed to continue selling the departing firm’s products, and International Harvester withdrew offices and sales from the state to headquarter in Memphis. These efforts to avoid Arkansas’s laws and to pressure the state’s leaders for changes proved successful. The 1913 Arkansas legislature amended the antitrust law to forestall most additional suits. Arkansas’s experience with antitrust became a prime example in showing that only the national government had sufficient legal authority and power to hold large corporations to account for abuses.

After a turn speaking on a Chautauqua circuit, Rogers served as prosecuting attorney of the Sixth Judicial District, consisting of Pulaski and Perry counties, from 1910 to 1914 and ran unsuccessfully for another term in 1926. Rogers helped create and was elected president of the newly established statewide Association of Arkansas’s Prosecuting Attorneys in 1910.

After 1914, Rogers had a long career as a criminal defense attorney. He and George W. Murphy were once called by a prosecutor “the two greatest criminal lawyers of Arkansas and of the entire South.” Rogers handled cases as they came, both obscure and high profile. He was part of the team in 1914 that successfully defended the U.S. senator from Oklahoma, Thomas P. Gore, from a suit by a woman who accused him of taking advantage of her in a Washington DC hotel room. But Rogers failed in defending Arkansas senator Samuel C. Sims from a conviction on bribery charges.

In an age notable for its many social and fraternal organizations, Rogers joined the Masons, Elks, Eagles, Shriners, Odd Fellows, and Knights of Pythias, often contributing oratory at meetings. He was a proud member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans and often spoke to groups of veterans. After 1915, along with many other Arkansas politicians, he joined the reborn Ku Klux Klan and eventually became a leader of a break-away group in Arkansas named the Independent Klan that opposed the state’s main organization.

He died at home at 2201 Chester Street in Little Rock on December 9, 1935, and is buried in the city’s Oakland and Fraternal Historic Cemetery.

For additional information:

Biennial Report of the Attorney General for the Period from December 15, 1910, to December 15, 1912. Little Rock: Democrat Printing and Lithograph Co., 1912.

Biennial Report of the Attorney General for the Period from December 15, 1912, to December 15, 1914. Little Rock: Democrat Printing and Lithograph Co., 1915.

Hempstead, Fay. “Robert L. Rogers.” Historical Review of Arkansas, Vo1. 2. Chicago: Lewis Publishing Co., 1911.

Herndon, David T. “Robert L. Rogers.” Centennial History of Arkansas, Vol. 2. Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1922.

“Hon. Robert L. Rogers, Attorney General.” Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, November 11, 1906, p. 9.

“Hon. Robert L. Rogers for Prosecuting Attorney.” Arkansas Gazette, November 7, 1909, p. 12.

Jacobson, Charles. The Life Story of Jeff Davis: The Stormy Petrel of Arkansas Politics. Little Rock, AR: Parke-Harper, 1925.

“Opening Speech of Hon. Robert L. Rogers.” Arkansas Gazette, October 4, 1903, pp. 13, 18.

“Mrs. Maria Rogers Dies.” Arkansas Gazette, June 4, 1917, p. 3.

“R. L. (‘Bob’) Rogers Succumbs.” Arkansas Gazette, December 10, 1935, p. 10.

“Robert L. Rogers for Pros. Atty.” Arkansas Democrat, November 7, 1909, p. 7.

“Robert Lee Rogers.” Arkansas Gazette, December 11, 1935, p. 10.

Willis, James F. “Antitrust Arkansas Politics during the Progressive Era.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 80 (Winter 2021): 436–467.

James F. Willis

Little Rock, Arkansas

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Law

Law Politics and Government

Politics and Government Robert L. Rogers

Robert L. Rogers

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.