calsfoundation@cals.org

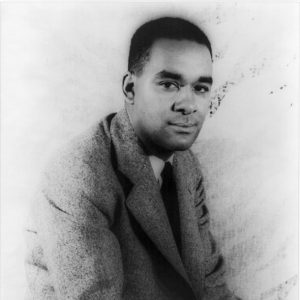

Richard Nathaniel Wright (1908–1960)

Richard Nathaniel Wright was a writer of fiction and nonfiction. His many works, influenced by the injustices he faced as an African American, protested racial divides in America. His most famous work, the autobiographical Black Boy, was a controversial bestseller that opened the eyes of the nation to the evils of racism.

Richard Wright was born on September 4, 1908, on a farm in Roxie, Mississippi, the son of Nathan Wright, a sharecropper, and Ella Wright, a teacher. He had one younger brother, Leon. The family’s poverty forced them to move around the South during Wright’s childhood. In Memphis, Tennessee, his father left the family, and in 1915, his mother put Wright and his brother in a Memphis orphanage after she became ill. A year later, Wright began school at the Howe Institute in Memphis. Wright and his mother and brother eventually moved to Elaine (Phillips County) in 1916 to live with Ella’s sister, Maggie, and Maggie’s husband, Silas Hoskins. Silas Hoskins owned a popular saloon in Elaine, and one morning he did not return home. Later that night, a black man came to the house to tell the family that Hoskins had been murdered by a white man coveting Hoskins’ lucrative saloon. Wright and his family fled to West Helena (Phillips County) for fear of their own lives, and later they went to Jackson, Mississippi.

In 1927, Wright and his aunt Maggie moved to Chicago, Illinois. Wright wrote his first novel, Lawd Today!, which was rejected during his lifetime and not printed until 1963, after his death. A year later, Wright began work for the post office. He was drawn to the Communist Party and its ideas on equality. Communist publications like Left Front and New Masses began publishing some of Wright’s radical poetry. In 1937, Wright moved to New York and was appointed coeditor of the Communist journal New Challenge. A year later, his Uncle Tom’s Children: Four Novellas was published to critical praise. He soon wrote Native Son (1940) and the autobiographical Black Boy: A Record of Childhood and Youth (1945) to just as much praise. Black Boy shows readers that Wright’s time spent in Arkansas was severely marred by the death of his uncle: “Uncle Hoskins had simply been plucked from our midst and we, figuratively, had fallen on our faces to avoid looking into that white-hot face of terror that we knew loomed somewhere above us. This was as close as white terror had ever come to me and my mind reeled. Why had we not fought back, I asked my mother, and the fear that was in her made her slap me into silence.”

While in New York, Wright married Dhima Rose Meadman, a ballet dancer, in 1939. He left her a year later and married Ellen Poplar, a fellow member of the Communist Party. They had two daughters, Julia and Rachel. Eventually, Wright left the Communist Party. Throughout the 1940s, Wright traveled across the United States giving lectures as he continued to write and spend time with his family in New York. Then, in 1946, Wright traveled throughout Europe spending much of his time in France. He and his family eventually settled in Paris. Wright was attracted to the freedom he felt there and became involved in Présence Africaine and the existentialist movement. While in Paris, Wright continued to give lectures and write essays on ideas of equality, but he also began to write haiku.

On November 28, 1960, Wright suffered a heart attack and died. He was cremated along with a copy of Black Boy.

For additional information:

Rowley, Hazel. Richard Wright: The Life and Times. New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2001.

Urban, Joan. Richard Wright. New York: Chelsea House, 1989.

Wright, Richard. Later Works. New York: Library of America, 1991.

Amber Hood

Mabelvale, Arkansas

Oh, how much I love the poetry and sad elegance of Black Boy. I have never read a book that touched me as deeply as this one. It should be mandatory reading in every junior high, high school, and university.