calsfoundation@cals.org

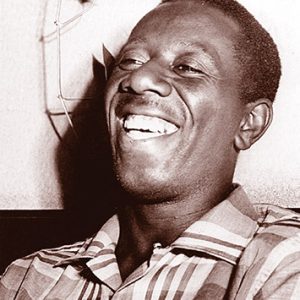

Reece "Goose" Tatum (1921–1967)

Reece “Goose” Tatum excelled at two sports, baseball and basketball, but is most famous for his basketball career with the Harlem Globetrotters. Known as “Goose” for his comic walk and for his exceptionally wide arm span, he is remembered more for his comic antics in games than for his athletic ability and accomplishments, which were considerable.

Reece Tatum was born on May 3 or 31, 1921, in El Dorado (Union County) or Hermitage (Bradley County)—sources differ on his birth date and birthplace. His father, Ben, was a part-time preacher and part-time farmer who also worked at the local sawmill, while his mother, Alice, raised their seven children, of whom Reece was the fifth, and also served as a domestic cook. He attended Booker T. Washington High School but may not have graduated, since he was employed at the sawmill and played baseball while still in his teens.

By 1937, Tatum was playing professional baseball for the Louisville Black Colonels of the Negro Leagues. He later played for the Memphis Red Sox, the Birmingham Black Barons (1941 and 1942), and the Indianapolis Clowns (1943 and 1946–1949). He reportedly played for a baseball team in Forester (Scott County) one summer as a young man, acquiring his nickname Goose there. Later, as part-owner of the team, he occasionally played for the Detroit Stars. Tatum played first base, where his long arms made him skilled at fielding the throws of his teammates. Early in his career, he began enlivening the games with comic antics, including catching throws behind his back, kneeling in mock prayer before going to bat, and inviting fans (especially children) onto the field during a game. These performances caught the attention of Abe Saperstein, who had founded the Harlem Globetrotters as a touring basketball team from Chicago in 1926.

In high school, Tatum had played basketball and football, as well as baseball. His natural athletic ability and sense of comic timing made him a natural fit for the Globetrotters. He soon became the team’s clown, eventually earning the nickname “Clown Prince” for his antics on the basketball court. Tatum’s comedic routines on the court were usually played off of his stature (he had an arm span of eighty-four inches). He often said, “My goal in life is to make people laugh,” which he deftly accomplished with such antics as playing hide-and-seek with the referees or replacing the original basketball with a trick one. Tatum studied clowns in movies and circuses, always seeking new elements to add to his routines. Hiding in the audience during a game, or pretending to spy on the opponents’ huddle, or pretending to faint until he was “revived” by the smell of his own shoes, Tatum helped to establish the Globetrotters’ reputation as an act that exceeded the usual showmanship of professional basketball teams.

Tatum played with the Globetrotters for the 1941 and 1942 seasons, and then he was drafted into the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II. He served at Lincoln Army Airfield in Nebraska, largely as an entertainer for the troops. After the war, he returned to play with the Globetrotters for another ten years. Tatum is credited with many inventive basketball moves, such as the hook shot, and he frequently scored more than fifty points in a game. At the same time, he continued his baseball career, playing in an all-star game in 1947 that drew the attention of major league scouts.

On occasion, Tatum failed to show up for scheduled games with the Globetrotters, sometimes missing as much as two weeks of work. Leaving the team for good in 1954, Tatum created his own touring basketball teams, including the Harlem Road Kings, Goose Tatum’s Harlem Stars, and Goose Tatum’s Harlem Clowns.

Many sources report that Tatum was moody and even violent when not performing. He is said to have stabbed a pitcher from an opposing baseball team with a screwdriver and to have been arrested on several occasions on charges ranging from attacking a police officer to nonpayment of taxes. Tatum was married three times, but little information is available about his marriages; he was not married at the time of his death.

Tatum died on January 18, 1967, in El Paso, Texas, of an apparent heart attack. He is buried at Fort Bliss National Cemetery in El Paso. Tatum was inducted into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame in 1974. Tatum’s jersey, No. 50, was retired on February 8, 2002, sixty years after his first season. His was the fourth number the Globetrotters had retired. On the same occasion, he was entered into the Globetrotters’ “Legends” Ring at Madison Square Garden. In 2011, Tatum was elected to be in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

For additional information:

“Goose Tatum Dies of Heart Seizure.” Arkansas Gazette. January 19, 1967, p. 4B.

“‘Goose’ Tatum.” Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. https://nlbemuseum.com/nlbemuseum/history/players/tatum.html (accessed December 18, 2025).

Krupsaw, Jeff, ed. Untold Stories: Black Sports Heroes before Integration. Marceline, MO: Walsworth Publishing, Co., 2002.

Vecsey, George. Harlem Globetrotters. New York: Scholastic Books, 1970.

Nikki Scott

Harding University

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

As a twenty-year-old Wheaton College student sports reporter, I was present at the last game Tatum played for the Globetrotters with the Washington Generals in Nov. 1952; they were entertaining the sailors of Great Lakes Naval Training Station in Illinois. After the game, Goose and Marques Haynes “disappeared”according to Chicago medianot to surface for several weeks later in Arkansas, where they had formed their own barnstorming team. There was no evidence that Globetrotter teammates or management knew of the intentions of the two stars in advance, and the game, as I recall, was a typical Trotter performance of skill and comedy. (I was present only because I was covering a football game between our college B-team vs. GLNTS B-team, and we guests were invited to stay afterward to watch the Trotters.)

In 1962, I joined Goose Tatum in Mobile, Alabama, after one game with the New York Wrens. I replaced Tint Brown as Goose Jr. and the Harlem Stars. The son of Goose Jr., the late Reece Goose Jr., was about two years old. Playing in a game featuring the All-stars from Kentucky and Kentucky State, Cliff Hagan and now Golden State Warriors head coach Steve Curr, Hagan was a no show. Goose was already upset because the IRS had taken our gate receipt in Fort Knox, Kentucky. Goose hadnt payed any taxes since 1955. The game began, and I stole a dribble from Curr. A foul was called. Goose agued the call. Curr came down the court again, another still, and Goose began to ague again. Goose said the referee used the N word. This was in Paducah, Kentucky. Goose slapped the referee and was taken to jail. That was the end of the tour. I enjoyed playing under the name of Goose Jr. and being his driver along with Mrs. Tatum. The rest is history, along with Nate Sweetwater Clifton and the other good players.

(2015) My mother knew him when she lived in a logging town called Forester, Arkansas. I have several books with his name in them. The town moved, but it has been having a reunion for sixty-two years. They have bricks with names on them, and there is one with his name. He lived in what they called Black Town. There was a fence that split the town. In third grade, she was part of having the fence removed.