calsfoundation@cals.org

Progressive Party

aka: Bull Moose Party

The Progressive Party, sometimes referred to as the “Bull Moose Party,” was a reform-oriented third-party political organization launched in 1912 primarily to promote the presidential campaign of Theodore Roosevelt. The party was on the ballot in forty-seven states that year, including Arkansas, where Roosevelt finished in third place. The Bull Moose Party in Arkansas effectively ceased operations with the 1914 election. In the end, the Progressive Party did little to alter the politics of Arkansas or spark any reform in the state.

Roosevelt, a former New York governor, U.S. vice president, and outspoken champion of reform, became president of the United States in September 1901 upon the assassination of President William McKinley. He ran for a full term in 1904, promising a reform package he called the “Square Deal” and also pledging not to run for another term as president.

He made efforts to reach out to Arkansas during his presidency. During the 1904 campaign, Roosevelt visited the World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri, and complimented the Arkansas exhibit, calling Arkansas “the Wonder State,” which would become its motto by the 1920s.

In the 1904 presidential election, Roosevelt, the Republican Party candidate, won 46,760 votes in Arkansas (or 40.19 percent) compared to 64,434 votes (or 55.38 percent) for Judge Alton B. Parker of New York, the Democratic candidate. Roosevelt won only twelve of the seventy-five counties in the state, mostly in western Arkansas. In fact, the Democratic Party won Arkansas in every presidential election between 1876 and 1964, the only state in the nation to do so. Nationally, Roosevelt won decisively, with 56.4 percent of the popular vote and 336 electoral votes compared to 37.6 percent of the vote and 140 electoral votes for Parker.

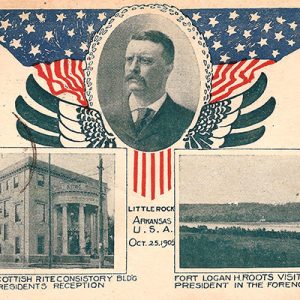

Roosevelt visited Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1905, becoming only the second president to visit the state. Roosevelt generally followed the suggestions of former Arkansas governor and U.S. senator Powell Clayton of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) for postmaster appointments in the state, while keeping Clayton as U.S. ambassador to Mexico. Roosevelt supported construction of new post offices in Arkansas and improvements to Fort Logan Roots in North Little Rock (Pulaski County). The creation of two national forests in the state was especially popular. In 1907, Roosevelt approved creation of the Arkansas National Forest near Hot Springs (Garland County), which was renamed the Ouachita National Forest in 1926. In 1908, Roosevelt created the Ozark National Forest in western Arkansas.

After his term in the White House ended in 1909, Roosevelt traveled extensively. By 1910, he was becoming increasingly disenchanted with his hand-picked successor, President William Howard Taft of Ohio, who had formerly served as secretary of war under Roosevelt. That year, Roosevelt visited Hot Springs and delivered a rousing speech before a crowd of 25,000 to share his ideas for a reform package he called the “New Nationalism,” an extension of his Square Deal and the heart of his Progressive Party platform.

In 1912, Roosevelt challenged Taft for the Republican nomination. Roosevelt campaigned actively, making two appearances in Arkansas in April, speaking to crowds in Fort Smith (Sebastian County) and North Little Rock. While Roosevelt won the Republican primary elections, most of the delegates needed to secure the nomination were chosen by state conventions and party leaders. In Arkansas, such men were opposed to Roosevelt and his reform ideas. At the Republican National Convention in Chicago, Illinois, in June, a dispute over delegates resulted in party leaders awarding most of the delegates to Taft, giving him the nomination along with Vice President James S. Sherman of New York as his running mate.

Roosevelt and his delegates stormed out of the convention in protest and quickly organized the Progressive Party, holding its own nominating convention in Chicago in August. Roosevelt was nominated with Governor Hiram Johnson of California as his running mate. The platform for the Progressive Party called for giving women the right to vote nationwide, a direct popular vote for U.S. senators instead of election by state legislators, an inheritance tax on millionaires, a national program of worker’s compensation for those injured on the job, national health insurance, a benefit program for senior citizens and the disabled similar to what Social Security would become in 1935, an eight-hour workday, strict campaign finance laws for political campaigns, and new antitrust legislation. Though these were considered radical ideas by many, most would be implemented later at the federal level.

The former president proclaimed, “I’m as fit as a Bull Moose,” which inspired Progressives to adopt the Bull Moose as the party’s symbol. His supporters were subsequently called the “Bull Moose Party” or “Bull Moose Progressives.” Critics, however, began calling the Progressives “Moosevelts.”

In Arkansas, Progressives attempted to create a viable party infrastructure. James Comer of Little Rock (Pulaski County) came to lead the party as editor of the Progressive Bulletin, which promoted Roosevelt’s candidacy.

The Democratic Party, seeing the deep split among Republicans, nominated Governor Woodrow Wilson of New Jersey, a former Princeton University president. Wilson, born in Virginia and raised in Georgia, was the first southerner to head a major party ticket since 1860. Early in his career, Wilson was offered a teaching position at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) but declined it in favor of Princeton. Governor Thomas Marshall of Indiana was nominated as Wilson’s running mate.

Though Wilson campaigned on a reform platform he called the “New Freedom,” he was sharply critical of Roosevelt’s ideas. He believed Roosevelt’s plans would rely too heavily on the power of the federal government, making workers “wards of the state.” Wilson instead called his program one for “the man on the make rather than one for the man already made.”

Arkansas politics had been dominated by the Democratic Party since the end of Reconstruction. Though the Republican Party was weak in Arkansas in 1912, it did have some semblance of campaign organization. In September, Roosevelt arrived in Little Rock and gave a widely publicized speech to the Deep Waterways Convention in which he supported conservation as well as flood control and improved navigation on the Arkansas River. His campaign was hampered by the lack of an organized party apparatus, however, and most prominent Republicans refused to back Roosevelt, preferring to stay with Taft instead.

Civil rights for African Americans and other minorities were not a priority for any party in 1912, including the Progressive Party. In 1901, Roosevelt had scandalized many white southern conservatives by inviting civil rights activist Booker T. Washington to dine with him at the White House. While this gesture thrilled many African Americans, Roosevelt did little more to alleviate segregation, even though a sizable portion of African Americans still identified with the Republican Party at this point. The Republican Party was increasingly divided on the issue of civil rights and African American leadership at the local level. Wilson would end up winning the African American vote nationally in 1912.

The Progressive Party appeared on the ballot in 1912 in every state except Oklahoma. Nationally, Wilson won with 41.84 percent of the popular vote and 435 electoral votes. Roosevelt placed second with 27.38 percent of the vote and 88 electoral votes. Taft finished third with 23.17 percent of the vote and only eight electoral votes in what became the worst showing for Republicans ever.

In Arkansas, Wilson won easily, carrying seventy-four of seventy-five counties. He earned 68,814 votes, or 55.0 percent. Taft came in second with 25,585 votes, or 20.5 percent. Roosevelt came in a close third with 21,644 votes, or 17.3 percent. Socialist Party candidate Eugene V. Debs of Indiana took 8,153 votes, or 6.5 percent; Prohibition Party candidate Eugene W. Chafin of Wisconsin won 908 votes, or less than one percent. Neither Debs nor Chafin had any significant impact on the election in Arkansas.

The split between Taft and Roosevelt allowed the Democratic nominee Wilson to win Newton County, a bedrock Republican county, by five votes over Taft. This was the first time the Democrats had won the county in a presidential election since 1860 and the last time until 1932. The only county not won by Wilson was Searcy County, won by Taft. The Democrats would not carry Searcy County at all between 1860 and 1932. Roosevelt, meanwhile, placed second in twenty-five counties, including Benton, Crawford, Bradley, Calhoun, Chicot, Crittenden, Garland, Pope, Pulaski, Lonoke, Dallas, and Jefferson. Roosevelt won 36.7 percent of the vote in Chicot County, his highest county-wide total in Arkansas, while also winning 35.8 percent in Crittenden County, 30.8 percent in Dallas County, and 24.7 percent in Pulaski County.

A brief attempt to keep the Progressive Party alive in Arkansas was made after 1912. After Arkansas governor Joseph T. Robinson of Lonoke (Lonoke County) resigned to take a seat in the U.S. Senate in March 1913, a special election was held that year to succeed him. George W. Murphy ran on the Progressive Party ticket in a four-man race that included Socialist Party candidate J. Emil Webber, Republican Party candidate Harry H. Myers, and the ultimate winner, Democratic candidate George W. Hays of Camden (Ouachita County). Hays won with a resounding 64.3 percent of the vote, compared to 10 percent for Murphy.

In the 1914 congressional election, L. C. Packard challenged the incumbent Democratic U.S. representative Otis T. Wingo of De Queen (Sevier County) on the Progressive Party ticket for the Fourth Congressional District, which took up most of southwestern Arkansas. Packard’s candidacy was the most prominent effort by the party that year, but he lost decisively, tallying just 1,135 votes, barely 18 percent, to Wingo’s 82 percent. The Bull Moose Progressive Party in Arkansas effectively ended with the 1914 election. Ultimately, the Progressive Party did little to affect the politics of Arkansas or the cause of reform in the state.

Roosevelt returned to the Republican Party and was considering a presidential run on the Republican ticket in 1920. He died in 1919, however. James Comer, state party leader, jumped to the far-right reactionary wing of the political spectrum and became the leader of the Ku Klux Klan in Arkansas as it revived itself in the 1920s.

A new Progressive Party emerged in the presidential election of 1924, largely unrelated to Roosevelt’s party of 1912 except in name and similar ideas of reform. These new Progressives nonetheless nominated U.S. Senator Robert M. LaFollette of Wisconsin for president and U.S. Senator Burton K. Wheeler of Montana for vice president. LaFollette earned less than 9.5 percent of the vote in Arkansas, far behind the winner of the state vote, U.S. Representative John W. Davis of West Virginia. This new incarnation of the Progressive Party disappeared in Arkansas after the 1924 contest.

For additional information:

Cooper, John Milton. Pivotal Decades: The United States, 1900–1920. New York: W. W. Norton, 1990.

———. Woodrow Wilson. New York: Vintage, 2009.

Cordery, Stacy. Theodore Roosevelt in the Vanguard of the Modern. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 2003.

Gatewood, Willard. “Theodore Roosevelt and Arkansas, 1901–1912.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Spring 1973): 3–24.

Historical Report of the Secretary of State, 2008. Little Rock: State of Arkansas, 2008.

Lewis, Todd E. “From Bull Mooser to Grand Dragon.” Pulaski County Historical Review 43 (Summer 1995): 26–41.

Moneyhon, Carl H. Arkansas and the New South, 1874–1929. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Morris, Edmund. Colonel Roosevelt. New York: Random House, 2011.

———. Theodore Rex. New York: Random House, 2001.

Pringle, Henry F. Theodore Roosevelt. New York: Harcourt Brace and Co., 1931.

Rosen, Jeffrey. William Howard Taft. New York: Times Books, 2018.

Woodward, C. Vann. Origins of the New South, 1877–1913. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1951.

Kenneth Bridges

South Arkansas Community College

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.