calsfoundation@cals.org

Pope County Militia War

The Pope County Militia War was a conflict between the Reconstruction government of the state and county partisans, some of them former Confederates, who opposed Reconstruction. It entailed the assassination of many local officials and is often seen as a prelude to the Brooks-Baxter War of 1874.

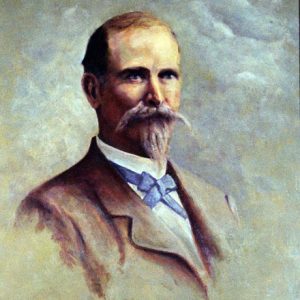

Pope County, lacking a large slave economy, had been divided in terms of loyalty during the Civil War, and those divisions ran high even after the formal end of hostilities. In 1865, Governor Isaac Murphy appointed Archibald Dodson Napier, a former Federal officer, as sheriff of Pope County. On October 25, 1865, he and his deputy, Albert M. Parks, were both shot from ambush as they rode horseback along the old Springfield road east of Dover, then the county seat. George W. Newton, a former Confederate major and later a Baptist preacher, was the assassin of Napier, though this was unknown at the time. Newton struck again on December 4, 1865, when he killed County Clerk William Stout, who had been elected to office before the Civil War, in his home. Morris Williams, who had succeeded Napier as sheriff, was killed in 1866 by Matt Hale while plowing in his field. Elisha W. Dodson was appointed sheriff, with John H. Williams, younger brother of Morris Williams, as deputy. Wallace Hakes Hickox was appointed by the governor to be county clerk after Stout.

Following these events, in the spring of 1867, two federal companies under a Major Mulligan were stationed in Dover to help the civil authorities bring order to the area. The troops remained until 1869, when Governor Powell Clayton removed them. However, violence flared up again with the July 5, 1872, assassination attempt upon Deputy Williams. In response, Dodson received permission from Ozro A. Hadley, who was serving as governor following Clayton’s 1871 resignation, to organize a company of militia to clamp down on the violence. On July 8, County Clerk Wallace H. Hickox, Sheriff Dodson, and William A. Stewart, the county superintendent of public instruction, arrested Nicholas J. (Jack) Hale (father of Matt Hale), as well as his son William, Joseph Tucker, and Isham Liberty West. The posse, taking their prisoners to Dardanelle (Yell County), crossed Shiloh Creek in the dark when shots were fired into the group of prisoners. Tucker and William Hale were shot from their horses; both were killed. West was thrown from his horse and hid in the brush, while Nicholas Hale fled and rode to Dover. Posse members maintained that they had been ambushed by unknown individuals attempting to free the prisoners and that the two dead men were shot while trying to escape, while the escaped prisoners averred that the posse had attempted to murder them, and even said that Dodson found Tucker alive though wounded and shot him in the head in the aftermath. The incident served to rile tensions even more in the county, and Stewart soon left the county.

On July 11, Hadley sent Adjutant General Daniel Phillips Upham to investigate, and Hadley and Judge W. W. Wiltshire visited Russellville (Pope County) and called for calm. For a while all seemed quiet. On July 25, Dodson and Hickox were bound over for trial, though they were never arrested and remained free.

On August 31, W. O. Cox, Reece B. Hogins, Ben Young, John Young, John Hale, Anderson Morgan, and others were indicted by the Circuit Court and charged with the assault of Dodson and Deputy Williams with intent to kill. However, Judge William N. May of Dardanelle recessed the court at the end of one day, perhaps because the men came to court with personal guards armed with shotguns and pistols. That same day, Hickox, Dodson, and Williams rode to Dover and began boxing up county records with the intention of taking the records to the small town of Russellville. Rumors spread that the town was to be burned by elements from outside. As they were leaving town, a shootout ensued between the three men and blacksmith W. Harry Poynter in which Hickox was killed. Later that day, at an inquest held by Justice of the Peace Allen Brown, Poynter was not charged. Shortly thereafter, that same day, Brown was shot by John Hale; Brown died on September 3, and Hale was never charged with the murder.

In response, the county was placed under martial law, with a regiment of state guards led by Upham there to keep the peace. With Upham was Captain George R. Herriot, who commanded a unit of African-American soldiers. An order was issued forbidding the carrying of arms and the disbursement at once of all forces. It called on all citizens to aid the military in keeping the peace. However, efforts toward peace remained difficult in the violent county. In September, Deputy Williams, while in the northern part of the county hunting for fugitives or attempting to recruit volunteers, was shot in the jaw and throat; he died on September 10.

Due to the continuing violence, John R. H. Scott and Williams Reynolds went to Little Rock (Pulaski County) to see the governor. In response to their entreaties, Hadley formed a peace commission and appointed A. S. Fowler as sheriff during Dodson’s suspension pending an investigation into the attack near Shiloh Creek. The governor’s actions likely prevented further violence, as an armed force of approximately 200 men was reportedly ready to drive the militia out no matter the consequences, while George Newton, who had previously assassinated a sheriff and county clerk, was heading down from Boone County with another sixty would-be guerrilla soldiers. For a while, the violent county was relatively calm.

On February 16, 1873, Captain Herriot returned to Dover and went to the courthouse. Plans had been made by a local group to kill him. Reece Hogins was to lure him from the courthouse and murder him in his grocery store but failed to do so. John Hale thus went into the courthouse and dragged the captain out into the hall. As Herriot got back to his feet, he reached for his gun to shoot Hale, but George Rye shot the captain first. At the coroner’s inquest, Hogins served as foreman of the jury, and, unsurprisingly, no charges seem to have been filed in Herriot’s murder.

Before dawn the following day, Dodson was shot at Perry’s Station, three miles east of Atkins (Pope County), while waiting to board a train bound for Little Rock. He lived until the afternoon of February 18. At one point, ten men were charged with the crime, but no one dared arrest them and set off a new round of violence. Judge William May stated that, should the men come to court in Russellville for trial, they would be permitted ten armed guards each for their protection. At noon on the first day of the trial, defendant John Hale, his fellow defendants, and their guards decided to kill the entire court and officials the following morning. However, the court adjourned that afternoon and was never reconvened, leaving those charged with murder to roam free.

Following the death of Dodson, J. B. Erwin of Russellville became sheriff until the fall election, when Joseph Petty, a former Confederate soldier, succeeded Erwin. Would-be murderer Reece Hogins was made chief deputy. The election of Elisha Baxter to the position of governor marked the formal end of Reconstruction in the state. A resurgent Democratic Party in the state essentially allowed Pope County’s violent insurgents and known murderers to assume command of the mechanisms of local government. With the state no longer enforcing policies contrary to local political opinion, unlike during Reconstruction, violence in the county ebbed. In the words of Pope County historian David L. Vance, “Peace was soon restored.”

For additional information:

Boyett, Gene W. “The Black Experience in the First Decade of Reconstruction in Pope County, Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 51 (Summer 1992): 105–119.

Reynolds, Thomas J. The Pope County Militia War: July 8, 1872, to February 17, 1873. Little Rock: Foreman-Payne Publishers, 1968.

Shull, Laura L. “Pope County Violence, 1865–1875.” Pope County Historical Association Quarterly 37 (June 2005): 2–27.

Vance, David L. Early History of Pope County. Mabelvale, AR: Foreman-Payne Publishers, 1970.

Kathleen Bell

Russellville, Arkansas

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Archibald Dodson Napier was my great-great-grandfather. My grandmother, Della Napier Qualls, told me the story many times, exactly as you recorded it, except she never knew the name of the “bushwhacker” who killed him and his deputy, Albert Parks, on Wednesday, October 25, 1865. Grandmother told me that Isaac C. Napier, brother of Archibald Dodson Napier, fought with Archibald in Co. H, 15th Ark. Militia, and he, too, was killed the same year, 1865, by “bushwhackers” while plowing a field at home. She said there was a big rock in Pope County that had blood stains of a Civil War soldier, where he fell. She saw it as a little girl and said that it was well known by all that saw it. She also said that all the rain that came never washed the stain away.