calsfoundation@cals.org

Pauropoda

Pauropods belong to the Phylum Arthropoda, Subphylum Labiata, Superclass Myriapoda, and Class Pauropoda. They are small, pale, millipede-like arthropods. There are about 830 species in twelve families worldwide, and they live under rocks in moist soil, leaf mold, and woodland litter. Only a single species, Eurypauropus spinosus, has been reported from Arkansas, but there are likely more that would be uncovered with further research.

The only known fossil pauropod is Eopauropus balticus, a prehistoric species known from mid-Eocene Baltic amber (40 to 35 million years ago). Because pauropods are normally soil-dwelling, their presence in amber (fossilized tree sap) is unusual, and they are the rarest known animals in Baltic amber. They appear to be an old group closely related to the millipedes (Diplopoda). However, they look more similar to centipedes, but strong evidence supports the Symphyla as the sister group of the Pauropoda.

There are two orders: the Hexamerocerata and the larger order Tetramerocerata. The former has a wholly tropical range in Brazil, continental Africa, Madagascar, and Seychelles, as well as Japan. The latter order, depending on various sources, possesses eleven to twelve families (Afrauropodidae, Antichtopauropodidae, Brachypauropodidae, Colinauropodidae, Diplopauropodidae, Eirmopauropodidae, Eurypauropodidae, Hansenauropodidae, Pauropodidae, Polypauropodidae, and Sphaeropauropodidae) and about 480 species that are subcosmopolitan, occurring nearly worldwide. In addition, the Hexamerocerata has a six-segmented and strongly telescopic antennal stalk and a twelve-segmented trunk with twelve tergites and eleven pairs of legs. The representatives are white and proportionately long and large. The one family in this order, Millotauropodidae, has a single genus and eight species. The Tetramerocerata has a four-segmented and scarcely telescopic antennal stalk, six tergites, and eight to ten pairs of legs. Representatives of this order are often small (sometimes minute), and coloration is white or brownish. Most species have nine pairs of legs as adults.

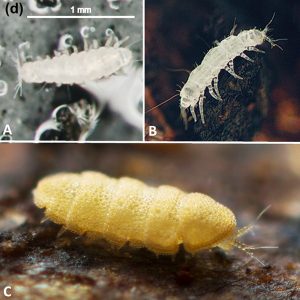

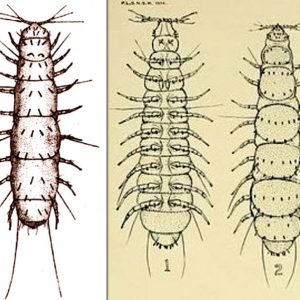

Pauropods are soft, nearly microscopic cylindrical invertebrates with bodies 0.5 to 2.0 mm (0.02 to 0.08 in.) long that are rarely encountered by the casual observer. The first instar has three pairs of legs, but that number increases with each molt so that adult species may have nine to eleven pairs of legs. They are eyeless and have no hearts, although they do have sensory organs that can detect light. Similar to those in millipedes and symphylans, the body segments have ventral tracheal/spiracular pouches forming apodemes, although the trachea usually connected to these structures are absent in most species. They possess long sensory hairs located throughout their body segments. Their head capsules show great similarities to millipedes, as both have three pairs of mouthparts and the genital openings occur in the anterior part of the body. Moreover, both groups have a pupal stage at the end of the embryonic development. Pauropods are usually either pale white or brown.

Pauropods can usually be identified because of their distinctive anal plate, which is a unique morphological characteristic of pauropods. Different species of pauropods can be identified based on the size and shape of this structure. Their antennae are branching, biramous, and segmented, which is also distinctive for the group.

Pauropods occur in moist soils, usually at densities of less than 100 per square meter (11.0 sq. ft.). They are cautious of light and will attempt to move away from light sources. Pauropods occasionally migrate upward or downward throughout the soil based on moisture levels. The also possess distinctive locomotory patterns characterized by rapid bursts of movement and frequent abrupt changes in direction. Although they cannot burrow, they can follow root canals and crevices in much deeper levels, down to the groundwater surface.

In terms of reproduction, pauropods are bisexual and progoneate. Male pauropods place small packets of sperm on the ground, which impregnates the females after she picks them up. Before the first larval instar appears, the egg develops in a short pupoid phase. In the Tetramerocerata, the first larval instar has three pairs of legs, and is then followed by instars with five, six, and eight pairs of legs, whereas in the Hexamerocerata, the first larval instar has six pairs of legs. Parthenogenetic reproduction seems to occur, particularly in areas with unfavorable environmental conditions.

Although the food habits of most species are unknown, pauropods are reported to eat a variety of minute items. Some do eat mold or suck out fungal hyphae; at least one species even eats root hairs. A single species was found feeding on and damaging African violet (Saintpaulia ionantha) cuttings in a greenhouse in the Netherlands.

Little is known of the pauropod species that occur in Arkansas. A single species, Eurypauropus spinosus, has been reported from the state. Specimens were taken from Pinnacle Mountain (Pulaski County) and Mount Nebo State Park (Yell County). There are almost certainly additional Arkansas species, and more work is sorely needed on the group.

For additional information:

Adis, J., Ulf Scheller, J. W. de Morais, and J. M. G. Rodrigues. “Abundance, Species Composition and Phenology of Pauropoda (Myriapoda) from a Secondary Upland Forest in Central Amazonia.” Revue Suisse de Zoologie 106 (1999): 555‒570.

Allen, Robert T. “Eurypauropus spinosus (Arthropoda: Pauropoda: Eupauropodidae) from Arkansas and a Key to the North American Eurypauropus Species.” Entomological News 101 (1990): 95‒97.

———. “First Record of the Genus Ribautiella Brolemann in the Western Hemisphere and Key to the Species of the World (Symphyla: Scolopendrellidae).” Journal of the New York Entomological Society 106 (1998): 199‒208.

Hagvar, S., and Ulf Scheller. “Species Composition, Developmental Stages and Abundance of Pauropoda in Coniferous Forest Soils of Southeast Norway.” Pedobiologia 42 (1998): 278‒282.

Minelli, Alessandro. “Class Chilopoda, Class Symphyla and Class Pauropoda.” Zootaxa 3148 (2011): 157–158.

Scheller, Ulf. “The Pauropoda (Myriapoda) of the Savannah River Plant, Aiken, South Carolina.” Savannah River Plant and National Environmental Research Park Program 17 (1988): 1–99.

———. “Pauropoda and Symphyla (Myriapoda) Collected on St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands.” Caribbean Journal of Science 25 (1990): 164–195.

———. “Pauropoda (Pauropodidae: Eurypauropodidae) from North-Western Thailand.” Tropical Zoology 8 (1995): 7–41.

———. “A Reclassification of the Pauropoda (Myriapoda).” International Journal of Myriapodology 1 (2008): 1–38.

———. “Records of Pauropoda (Pauropodidae, Brachypauropodidae, Eurypauropodidae) from Indonesia and the Philippines with Description of a New Genus and 26 New Species.” International Journal of Myriapodology 2 (2009): 69–148.

Scheller, Ulf, P. Brinck, and P. H. Enckell. “First Record of Pauropoda (Myriapoda) from Borneo.” Stobaeana 1 (1994): 1–14.

Scheller, Ulf, and Jörg Wunderlich. “First Description of a Fossil Pauropod, Eopauropus balticus n. gen. n. sp. (Pauropoda: Pauropodidae), in Baltic Amber.” Mitteilungen des Geologischpaläontologisches Institut und Museum, Universität Hamburg 85 (2001): 221–227.

Chris T. McAllister

Eastern Oklahoma State College

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.