calsfoundation@cals.org

Nathan Lacey (Lynching of)

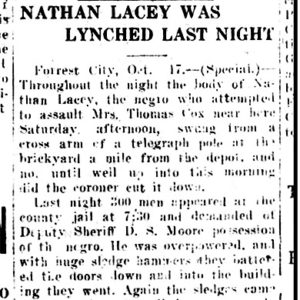

On October 16, 1911, an African American man named Nathan Lacey was lynched in Forrest City (St. Francis County) for allegedly attacking the wife of his employer, Tom Cox.

Mrs. Cox is probably Elizabeth Cox, who in 1910 was living in Franks Township with her husband Tom and their one-year-old son, Thomas. There were three African American men by the name of Nathan Lacey or Lacy listed in St. Francis County in 1910. The first was Nathan Lacy Jr., born in Mississippi around 1881, who was a widower working as a farm laborer in Madison Township. He had three children the age of eight and under. Nathaniel Lacy, born in Mississippi around 1885, was single and living with his mother, Angeline Lacy, in L’Anguille Township and working as a farm laborer. A seventy-year-old Nathan Lacy was living in Forrest City with his wife and two grandchildren.

According to the newspapers, Lacey attacked Mrs. Cox at her home near Forrest City, where he had been employed for the last three years. The Arkansas Democrat reported that the date of the attack was Saturday, October 14. However, the Arkansas Gazette reported it was on October 15. The Democrat report indicated that Mrs. Cox, badly bruised around the neck and in critical condition, was already in poor health, “and it is feared that her terrible experience of Saturday afternoon will have a most serious effect upon her.”

Reports in the Arkansas Gazette indicate that Lacey had been captured by October 16, and as the news spread, small groups of men began to assemble in the city, eventually resulting in a large gathering. The authorities, who feared violence, refused to turn over the prisoner and offered to call a special court session and give Lacey a speedy trial. The crowd was not satisfied, and a mob estimated at 200–300 people assembled that night, went to the jail with sledgehammers and crowbars, and broke their way in. Lacey was dragged from the jail and marched about a mile to an old brickyard outside of town. According to the Democrat, on the way, he “shrieked and begged for his life, praying to his God for mercy and to his captors for time to prepare to meet his fate.” The Standard noted that he was then strung up to a telegraph pole. After a few seconds, he was let down so he could make a statement. He pleaded for mercy but was pulled up again and “left suspended.” All accounts indicate that the members of the mob were not drunk or riotous, nor did they fire a shot. The Southern Standard indicated that the men “silently marched back to the city after their work was done.”

Lacey’s body was left to hang overnight, and, according to the Democrat, the following morning the coroner ruled that he had “come to his death at the hands of a mob, the members of which were unknown to him.” On October 18, the Arkansas Democrat published an editorial titled, “Do Lynchings Pay?” In answer to this question, which had been asked many times over the years, the Democrat concluded that lynchings can be looked at in either an abstract or concrete way. Addressing them in the abstract does no good. It is looking at concrete cases, such as Lacey’s, that is most informative. Citing the fact that there was “practically no doubt that he would have been convicted and legally executed,” the writer asked if it would have been better to try and hang him than “the wreaking of summary vengeance upon him by a gathering of 300 men without warrant of law?” The writer said that the feelings of the woman’s family and friends should be considered, although no one close to Mrs. Cox seemed to be members of the mob. In such a case, the lynching would then be the result of county residents wanting to give a warning, and prevent Lacey and others like him from committing similar assaults. It is doubtful, however, because of the lack of education and intelligence of such “brutes,” that such lynchings have “any salutary effect upon others of their race who might contemplate such an act.” However, when an attacker is tried and jailed, the circumstances are widely discussed and weigh “more or less heavily upon even the poor mentality of the average black.” The writer thus drew the conclusion that it is useless to preach moderation to the assault victim’s family and friends, but that random mobs might keep this in mind before they proceed.

Despite reports of Elizabeth Cox’s critical condition, she did not die as a result of the attack. She died in 1961 and is buried beside her husband in Mt. Forest Cemetery in Forrest City.

For additional information:

“Do Lynchings Pay?” Arkansas Democrat, October 18, 1911, p. 6.

“Nathan Lacey was Lynched Last Night.” Arkansas Democrat, October 17, 1911, p. 1.

“Negro Assailant Lynched.” Southern Standard (Arkadelphia), October 19, 1911, p. 2.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Nathan Lacey Lynching Article

Nathan Lacey Lynching Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.