calsfoundation@cals.org

Mountain Home Lynchings of 1894

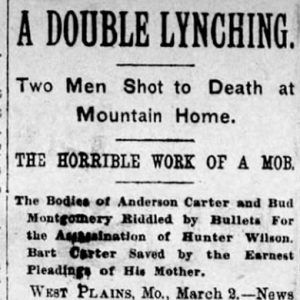

Anderson Carter and his nephew Jasper Newton, accused of murdering a wealthy cattleman, were shot to death by an armed mob in the Mountain Home (Baxter County) jail on February 27, 1894.

Hunter Wilson, who lived in Baxter County near the Missouri state line, was robbed and murdered at his home on December 18, 1893. His wife was also shot but survived. Several people were arrested on suspicion of being the killer, but only J. W. McAninch, Wilson’s partner in a cattle business, was kept in jail after Wilson’s wife voiced her suspicions that he was one of the masked men who raided their house.

Among the witnesses at McAninch’s evidentiary hearing were Anderson Carter, Carter’s twenty-two-year-old son Bart, and Carter’s nephew Jasper Newton; the Yellville (Marion County) Mountain Echo said Jasper Newton was an alias for Bud Montgomery of Clay County, who “belonged to a clan of horse thieves and is wanted in that county now for murder.” The three gave testimony indicating McAninch’s guilt, and he was jailed even though his attorney, Jerry South, provided evidence that Bart Carter’s boot print matched one found at the crime scene.

On February 22, 1894, South “procured” the arrests of the Carters and Newton, and two days later Bart Carter was taken from the jail and—“induced by promises of leniency” and a pledge that he would not be returned to the Mountain Home jail—confessed to the crime, which he said was his father’s idea. He said Anderson Carter told him to go with Newton to Wilson’s home, “and if he failed to do his part he would be killed.” The elder Anderson planned to go turkey hunting with neighbor Dow Bryant in order to have an alibi.

Bart Carter and Newton, who promised no one would be hurt, went to Wilson’s home on December 18, 1893, and donned masks, drew guns, and entered the house. Wilson “threw up his hands and got up, and Newton shot him almost instantly,” then shot Wilson’s wife as she tried to flee.

The younger Carter led authorities to where the stolen money was hidden, digging up $355 in gold buried 300 yards from Anderson Carter’s house and $365 in currency stuffed in a quinine bottle and buried in Carter’s stable.

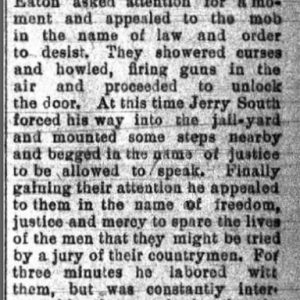

On the evening of February 27, 1894, a mob estimated at anywhere from 150 to 500 people marched against the jail. Sheriff W. F. Eaton asked them “in the name of law and order to desist,” but “they showered curses and howled in fury, firing in the air” and unlocked the door, whereupon they overpowered Eaton, the jailer, and ten guards.

The “poor wretches begged for mercy,” a newspaper reported, as the mob’s leader called on three men, and “three big fellows masked, stepped forward and commenced firing into their bed with Winchesters and shotguns,” loosing four or five volleys. The wounded Newton begged for water, and the mob leader, “seeing they had yet a spire of life remaining, ordered another volley.” Satisfied that Anderson Carter and Newton were dead, the mob left, “and in five minutes all had disappeared, leaving no trace as to their identity.”

The coroner ruled the two men dead of “gun shot wounds from the hands of unknown persons, acting as a mob or unlawful posse.” Carter and Newton were buried in a single unmarked grave in the paupers’ lot of the Mountain Home Cemetery. The Arkansas Gazette observed that “sentiment seems to be that justice was done, though somewhat informally.”

McAninch was freed, and Dow Bryant, who had provided Anderson Carter with an alibi, “has gone crazy. He was afraid of Carter and his connection with the case has unhinged his mind.” Though Governor William Fishback offered a $200 reward for the arrest and conviction of lynch mob members, and most people believed the killers were from Baxter and Fulton counties and Ozark County, Missouri, none appear to have been arrested for the murders.

Despite the promise of leniency, Bart Carter was tried for Wilson’s death in October 1894, convicted of first-degree murder, and sentenced to hang on December 21. On October 22, 1894, ten masked men approached the jail, got the key from the jailer’s wife, and freed Carter, with a newspaper writing that “it is supposed that it was done by the same mob” that had killed his father. An Arkadelphia (Clark County) newspaper mused that “an effort to capture Carter will probably be made, but the chance is very slim, as the sentiment of the people is against hanging him.” Attorney Jerry South stated that he “did not think very many would exercise any great amount of diligence in hunting him down.” Bart Carter apparently was never taken back into custody.

For additional information:

“Another Murderer to Hang,” Arkansas Gazette, October 11, 1894, p. 5.

“Arkansas News.” Arkansas Gazette, March 6, 1894, p. 1.

“Arkansas News: the Mountain Home Massacre” Arkansas Gazette, October 25, 1894, p. 1.

“Bloody Baxter.” [Yellville] Mountain Echo, March 16, 1894, p. 4.

“A Double Lynching.” Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, March 2, 1894, p. 3.

“The Liberation of Bart Carter.” Arkansas Gazette, October 26, 1894, p. 6.

Messick, Mary Ann. “Murder Most Foul! Death Come Calling to Hunter Wilson in 1893.” Baxter Bulletin, July 21, 2014, pp. 1A, 8A.

Messick, Mary Ann. “Vigilante Justice Comes to Mountain Home.” Baxter Bulletin, July 28, 2014, pp. 1A, 8A.

“Released By His Friends.” [Arkadelphia] Southern Standard, November 2, 1894, p. 1.

“Reward for Members of a Mob.” Osceola Times, March 31, 1894, p. 3.

“Swift Justice.” Arkansas Gazette, February 28, 1894, p. 1.

Mark K. Christ

Central Arkansas Library System

Law

Law Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Mountain Home Lynching Article

Mountain Home Lynching Article  Mountain Home Lynching Article

Mountain Home Lynching Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.