calsfoundation@cals.org

Moses J. "Chief" Yellow Horse (1898–1964)

Moses J. “Chief” Yellow Horse (sometimes rendered YellowHorse or Yellowhorse) is believed by some to be the first full-blooded Native American to play baseball in the major leagues. He spent one celebrated season pitching for the Little Rock Travelers in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1920, which catapulted him to the peak of his short and tragic career. The Pittsburgh Pirates bought “Chief” Yellow Horse’s contract after that season, and he arrived in Pennsylvania in 1921 amid acclaim and high expectations, owing to a lightning fastball that had terrified and struck out so many batters in the Southern Association that Little Rock had won its first-ever baseball championship. In Little Rock, he made a lifetime friend of writer Dee Brown, who later authored Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. Brown also wrote a novel called Yellowhorse.

Moses J. Yellow Horse (or “Mose Yellowhorse,” as his tombstone calls him) was born on January 28, 1898, on a reservation in the Oklahoma territory to Thomas Yellow Horse and Clara Ricketts Yellow Horse. His father’s Pawnee family and the rest of the Skidi (or Wolf Band) tribe, rich with centuries of mysticism and farming in Nebraska, had been forced by the U.S. government to leave there in 1875 and walk to poor land south of the Arkansas River in northern Oklahoma, where they were placed into four bands or camps. Many died along the way, and disease and starvation killed many others in the years afterward. In fifteen years, half of the tribe had died, leaving a population of fewer than 1,400 when Moses was born. He was steeped in Pawnee traditions and grew up as a jokester. He and his father worked in Pawnee Bill’s Wild West shows and he got a reputation on the reservation as a comedian.

He and his father farmed and hunted. Although perhaps only a legend, Moses was supposed to have developed his powerful pitching arm by throwing stones at small game—rabbits, squirrels, chipmunks, and birds—to furnish the family’s protein. At manhood, he was five feet ten inches tall and weighed 180 pounds, but he was unusually broad-shouldered and had powerful arms. The government’s Indian agency directed that he attend the Chilocco Indian Agricultural School, where he developed his baseball skills. He won seventeen games for the school without a loss in 1917 and began playing for traveling semiprofessional and professional teams, where his reputation for nearly unhittable pitches and exploits on and off the field spread across Oklahoma and into Arkansas.

The Little Rock Travelers—the team that became the Arkansas Travelers in 1957—signed Yellow Horse to a contract and brought him to town with some fanfare, including gossipy and humorous articles on the sports pages of the Arkansas Democrat and Arkansas Gazette. Norman “Kid” Elberfeld, the Travelers’ manager and a former major league star, had batted against the legendary Walter Johnson and said Chief Yellow Horse’s pitches were at least as overpowering as Johnson’s. “Chief” had become a common sobriquet for Native American athletes, applied by newspapers to nearly all who came to town. Big crowds turned out to see the Indian stars. Three years before Yellow Horse came to Little Rock, “Chief Benjamin Tincup,” who had starred in the Texas-Oklahoma League, was a regular for the Travelers, playing in the outfield and often pitching. Tincup had pitched a rare perfect game for the Travelers, allowing no batter to reach base, and when he reached the major leagues—with the Philadelphia Phillies—Chief Tincup singled in his first at-bat. Arkansas baseball fans were excited as the season approached in the spring of 1920 with the new Native phenomenon joining the Travelers.

Yellow Horse’s debut in Little Rock would coincide with another melodrama. The opposing team was the Chicago White Sox, which had won the National League pennant the previous fall but which by the spring was mired in the most infamous episode in baseball history—the “Black Sox Scandal.” Eight members of the team were accused of throwing the World Series to the Cincinnati Redlegs and taking bribes from a gambling syndicate run by Arnold Rothstein. Newspapers were filled with commentary and barbs about the White Sox, which had become the “Black Sox” in much of the press. The Sox were traveling around the South in exhibition games before the start of the new season. The stands at Kavanaugh Field (later West End Park) were packed to see White Sox legends like Shoeless Joe Jackson and Eddie Collins—and the Travelers’ twenty-two-year-old Yellow Horse. Elberfeld sent him to the mound in the middle innings, and he finished the game but allowed four runs, which the Gazette article about the game blamed on misfortunes not caused by Yellow Horse.

Under the heading “‘Yellow Pony’ Shows Class,” the Gazette reported: “The fans had heard a lot about his speed ball and they wanted to see if it really was as fast as advertised. Most of them were convinced. The Chief’s notion of a change of pace is to shift from the fast ball to a faster one.” Yellow Horse proved to be as wild as he was fast, throwing blazing balls all around the batter’s box, often at batters. Elberfeld had him always take a step toward the plate as he delivered the ball, and Yellow Horse became briefly legendary for his control rather than his wildness. Both daily papers contributed to the Chief’s legend with quips and humorous slurs about Indians, such as saying he was swinging a bat rather than a tomahawk. Gazette sports editor Ben Epstein wrote that Yellow Horse was “faster than the firewater he quaffed.”

“Two thousand Little Rock baseball fans went out to Kavanaugh Field yesterday to see Moses Yellow Horse pitch,” the Gazette reported. “Ten New Orleans batters also were there. Although they were closer than the two thousand, the ten saw less of Moses’s pitching than did the spectators.” At the end of the season, Yellow Horse had led all Southern Association pitchers with a .750 winning percentage. In the last game, Yellow Horse pitched the Travelers to a 1–0 victory over the Nashville (Tennessee) Volunteers to win the pennant. Owing largely to Yellow Horse’s presence on the field, attendance that season set a record for Little Rock, which went unbroken for thirty-one years.

Dee Brown was a teenager when he went to see Yellow Horse pitch and became his lifelong friend. Seventy years later, he would say, “I learned from Moses Yellow Horse that American Indians, even fierce-looking ones, could be kind and generous and good-humored and faithful friends.” Children could get in to see a game for free by retrieving a foul ball or homerun and presenting them at the gate, and Yellow Horse would sometimes slip Brown and others a ball through the fence. Afterward, Brown scorned all the negative movie accounts of frontier Indians. His friendship with Yellow Horse shaped his career writing about the West and history, including Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.

The Pittsburgh Pirates purchased Yellow Horse’s contract when the season ended in September, and his arrival at Pittsburgh the next spring was met with the same anticipation as there had been in Little Rock, but ultimately with bitter results. His drinking bouts and stunts with Walter V. “Rabbit” Maranville—while entertaining to the other players, opponents, and fans—became a problem. The manager decided to room with the two players on road trips to prevent hijinks that were distractions to the team. While the manager was at a late movie, Yellow Horse and Maranville caught pigeons that sailed past their sixteenth-floor hotel window and stuffed them into the manager’s closet. Late that night, when the two players were asleep, the pigeons flushed out into the room when the manager opened his closet.

While Yellow Horse took all the good-natured taunts from teammates and fans about being a “savage,” it was different when he was on the mound. The baseball legend Ty Cobb taunted him and did a war dance around home plate in an exhibition game in Detroit, and Yellow Horse beaned him when Cobb finally stepped to the plate. Much later, when Babe Ruth taunted him jokingly in an exhibition game in Oklahoma, an angry Yellow Horse struck him out twice. He won five games and lost three in his first season, with a respectable 2.98 earned-run average.

By midseason in 1921, Yellow Horse’s drinking and then his injuries, whether self-inflicted or not, were causing concerns for the Pirates management. Yellow Horse injured an arm late in the season, underwent surgery, and was never the same. He was injured again early in the 1922 season, rumored to be the result of a drunken fall. The Pirates were mediocre, and by midseason in 1922 the team had changed managers. Yellow Horse was benched and his major-league career was over. He had earned $1,650 with the Pirates in 1921 and $2,700 in 1922. The team traded him to Sacramento in the Pacific League, where he played briefly. He played some in the minor leagues and in semiprofessional games again, but he had become a disgrace in his Pawnee tribe. In 1945, he suddenly stopped drinking, stuck to his sobriety, and regained celebrity in the tribe. He worked as a minor league umpire, a groundskeeper, and as the coach of an all-Indian team that barnstormed around the South in the 1950s. He was inducted into the American Indian Athletic Hall of Fame and into the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame. His baseball glove remains on display at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York.

Chester Gould, who created the Dick Tracy comic strip, was born on the reservation with Yellow Horse. The hero of one of the Dick Tracy episodes was Chief Yellowpony, who helped capture the evil siblings Boris and Zelda Arson.

Biographies said Yellow Horse never married, but a 1934 census of the Pawnee reservation showed him as having a wife, Beatrice Lane Yellow Horse, a one-fourth Pawnee, who was sixteen years old when they married.

Yellow Horse died on April 10, 1964, and is buried in Northern Indian Cemetery in Pawnee County, Oklahoma.

For additional information:

Berger, Ralph. “Moses Yellow Horse.” Society for American Baseball Research. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/moses-yellow-horse/ (accessed April 22, 2022).

Fuller, Todd. 60 Feet, Six Inches and Other Distances from Home: The Baseball Life of Moses YellowHorse. Duluth, MN: Holy Cow! Press, 2002.

———. “Moses J. YellowHorse.” Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=YE022 (accessed April 22, 2022).

“Moses YellowHorse.” The Baseball Encyclopedia, 10th ed. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1996.

“Travelers Lose Carnival of Hits to White Sox.” Arkansas Gazette, April 7, 1920, p. 14.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Recreation and Sports

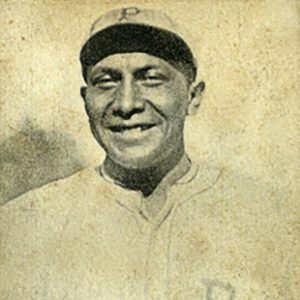

Recreation and Sports Yellow Horse Baseball Card

Yellow Horse Baseball Card  Moses "Chief" Yellow Horse

Moses "Chief" Yellow Horse

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.