calsfoundation@cals.org

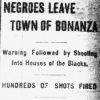

Little River County Race War of 1899

The Little River County Race War occurred in March 1899 in southwestern Arkansas and entailed the murder of at least seven African Americans throughout Little River County. The reported impetus for this race war was the murder of a white planter by a Black man, but white fear of “insurrection” on the part of Black residents quickly manifested itself into a campaign of violence and terror against African Americans.

During the last half of the nineteenth century, lynchings were widespread in Arkansas, especially in the southern part of the state. A number of factors contributed to this racial animus. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the Black population of Arkansas increased greatly, mostly due to recruiters who canvassed the Southeast to lure Black farm laborers to the state. The Black population in many southern counties in Arkansas soon exceeded the white, and this new workforce provided lower-paid competition for local white workers. As a result, during the 1890s, the state began to pass Jim Crow laws that limited the rights of Black citizens. Although the number of lynchings decreased nationwide between 1890 and 1899, the level of violence in Arkansas was high.

Early accounts of the race war began to appear in newspapers across the nation on March 21, 1899. The trouble started when an African American named General Duckett murdered planter James Stockton at his home on Saturday, March 18. According to an article datelined Texarkana (Miller County), March 22, and published in the Houston Daily Post the following day, Duckett was a “fomenter of racial troubles and…had often tried to organize the Blacks of that section against the whites.” Reports indicated that as he was fleeing the scene of the crime, “he saw several negroes at their homes, told them what he had done, and said that more white men in Little River County would share the same fate as Stockton if his color would follow him.” According to the Atlanta Constitution, the motive for this particular crime lay in the fact that Stockton had met with Duckett to tell him to cease his activities or risk being called before a grand jury.

Accusations of “insurrection” were commonly laid upon African Americans who were politically active and/or had committed a crime against a white person. Rumors of full-blown insurrection were part and parcel of the 1883 Howard County Race Riot, the 1892 Hampton Race War, and the 1919 Elaine Massacre, though in none of these cases did evidence of a full-blown campaign against local whites ever actually arise.

On March 21, Duckett surrendered after hiding out in the Red River bottoms. The sheriff took him to the crime scene near Rocky Comfort (Little River County) and then began to escort him to what was then the county seat, Richmond. A few miles into the trip, a mob (numbering approximately 200 in some accounts) overtook them, took Duckett from the sheriff, and “within a few minutes his dead body was dangling from a tree.” Duckett reportedly confessed to the crime before he was hanged. According to some accounts, a few African Americans who disapproved of Duckett’s activities actually participated in the lynching, although they refused to bury the body afterward; some reports hold that the lynching of Duckett occurred at the exact location where he had murdered Stockton.

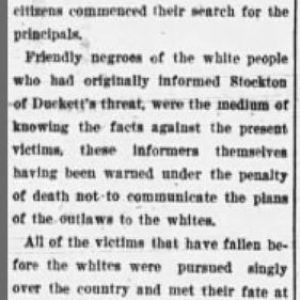

The murder of Duckett did not, however, sate the mob, especially given the rumors of Black insurrection that were spreading. After Stockton’s murder by Duckett, it was reported that twenty-three (or thirty-three) African Americans were involved in a plot to kill white people. According to the Nebraska State Journal, all those in the plot were known, and “small parties of white men, varying in number from twenty-five to fifty, are scouring the country for them. Whenever one is found he is quickly strung up, his body perforated with leaden missiles to make sure of their work and the mob hastens on in quest of its next victim.” On March 23, the Mena Star reported that “seven negro men have been lynched by the citizens of that section.…All of the victims that have fallen before the whites were pursued singly over the country and met their fates at different times and in different localities. In the gang that was plotting for a race war there were thirty-three negroes, and it is likely that the entire number have been strung up in the thickets.”

According to reports from nearby New Boston, Texas, that same day, “This morning Benjamin Jones was found dead on Hurricane Bend and from New Boston it is learned that Joe King and Moses Jones were found hanging to trees at Horseshoe Curve today. Another Jones is missing.” (There is confusion here about whether Joe King was killed or just beaten and let go. Some lists of the dead report that Adam King, not Joe King, was the one killed. Others describe two incidents involving Joe King, one the beating and the other his lynching.) Most of these were victims of lynchings, with the bodies left “hanging to trees in various parts of the country, strung up wherever overtaken.” One victim who tried to escape was shot and thrown into the river. Among those dead were General Duckett, Edwin Godwin, Adam King, Joseph Jones, Benjamin Jones, Moses Jones, and an unknown man. In addition, Joe King and John Johnson had been captured by mobs and whipped. After being turned loose, they disappeared. The county’s Black citizens panicked and immediately began leaving the area. Three wagonloads crossed the Red River at Index (Miller County) in the middle of the night and made it to Texarkana.

According to the Arkansas Gazette, the three Jones brothers were said to have been “intimate with the assassination of Stockton and it was discovered that they were leading a scheme to avenge their comrade’s death.” A few days later, the paper’s report was somewhat different. Joe King had apparently refused to give up his gun, saying he wanted it for self-protection. He and one of the Jones brothers had reportedly made offensive comments about Stockton’s murder. Goodwin and Moses Jones were killed because Moses Jones’s wife had prepared food for Duckett while he was in hiding and Goodwin had delivered it to him.

On March 24, the San Francisco, California, newspaper the Call noted that Joe King’s crime was to say that Stockton should have been murdered even earlier. According to the Call, Goodwin, a former employee of Stockton’s, was actually lynched in Bowie County, Texas, just across the Red River from Stockton’s farm. The next day, the New York Times reported that Joe King and Moses Jones had been hanged or shot, and a third man had been found near them in the Red River bottoms between New Boston and Rocky Comfort, stripped totally naked. According to the Times, a justice of the peace had held an inquest to look into these deaths and proclaimed that the victims had died “by natural causes or were frozen to death. The verdict is regarded as a gruesome joke.”

While many sensational stories were coming out of Texarkana, it was impossible to get accurate information. According to the Times, “One report states that the whites are still out in organized posses hunting the leaders in the negro revolutionary plot with the avowed intention of hanging them wherever found. Another report states that the negroes are recovering from their panic and terror and are securing arms and threaten vengeance on the whites….A negro who arrived here to-day from Wilton says that every negro in the neighborhood of Rocky Comfort and Richmond has left his home and is afraid to return. A large number of them have crossed Red River and gone into Bowie County in Texas. He says more negroes have been killed than has yet been reported.”

On March 26, the Times reported that the county was quiet, with no signs of further trouble: “It is impossible to learn how many negroes have really been lynched as nearly all the colored population has fled. The few remaining negroes are still in a state of great excitement. They assert positively that a dozen or more men have been killed in the Red River bottoms, mentioning names of negroes who have disappeared since the lynching of Duckett to substantiate their assertions. Two wagonloads of Blacks arrived in Texarkana to-day [March 25] from Little River County.”

This is the last account of the incident in the national press. There was one final article, however—an editorial published in the New York Sun on May 15. The Sun came to this notable conclusion: “While it is not known just how many were killed, ten are already reported. But strange to say, not one of those reported to be organizing to kill off the whites did anything in the way of defending himself. Hence it is clearly evident that the white men of the section were murdering many defenceless negroes to avenge the death of one white man.”

For additional information:

“All Quiet at Texarkana.” New York Times, March 26, 1899, p. 4.

Finley, Randy. “A Lynching State: Arkansas in the 1890s.” In Bullets and Fire: Lynching and Authority in Arkansas, 1840–1950, edited by Guy Lancaster. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018.

“Is the South Becoming Barbarous?” New York Sun, May 15, 1899, p. 6.

“Lynchings in Arkansas.” New York Times, March 25, 1899, p. 4.

“Murderer is Mob’s Victim.” Atlanta Constitution, March 22, 1899, p. 2.

“No More Killed.” Arkansas Gazette, March 25, 1899, p. 1.

“Race War is On. Whites of Arkansas Killing off the Colored Men.” Nebraska State Journal, March 24, 1899. Online at http://yesteryearsnews.wordpress.com/2009/01/19/little-river-county-arkansas-lynchings-1899/ (accessed February 7, 2024).

“Seven Negro Men Lynched.” Arkansas Gazette, March 24, 1899, p. 1.

Stockley, Grif. Ruled by Race: Black/White Relations in Arkansas from Slavery to the Present. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009.

“Tried to Stir up Trouble: Duckett wanted a General Assassination of Whites.” Houston Daily Post, March 23, 1899, p. 6.

“A War of Races Rages in Arkansas.” The Call (San Francisco, California), March 24, 1899, p. 1.

“A Wholesale Lynching.” Mena Star, March 30, 1899, p. 5.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Presbyterian College

Little River County Lynching

Little River County Lynching  Little River County Lynchings

Little River County Lynchings

There is a community named Jewel, Arkansas, in between Horatio and Crossroads, Arkansas, just off Highway 41, and there is a tree down that road where one of the Black men was hanged. This may have been later; I am not sure. My grandfather owned a store at Jewel, and there was a Black man who would come all the way from Horatio to have his corn ground because he was afraid to go to any of the other stores in the area. It is appalling what was done and is still being done to our Black citizens. In the town of Winthrop, Arkansas, there was a sign that my older sisters can remember as you came into town that said “N—– don’t let the sun go down on your back.” To me, this sign tells you something else: the prejudiced knew their deeds were wrong because they did them at night to be hidden, from who? God? I think he knows and I think he will be the final judge of all these matters.