calsfoundation@cals.org

Lincoln High School (Star City)

Lincoln High School was a school for African Americans located on the northwestern side of Star City (Lincoln County) at 507 Pine Street. The school, which took its name from the county, was established in 1949 following the consolidation of black schools in the communities of Cornerville, Cole Spur, Star City, Bright Star, Sneed, Richardson, Bethlehem, Mount Olive, Saint Olive, and Sweet Home. None of these schools went beyond the eighth grade, leaving a large segment of Lincoln County’s African-American students with no local high school to attend.

Charles R. Teeter was the superintendent, and Ruth Teal was hired as Lincoln’s first principal. In the first school year of Lincoln’s existence (1949–50), only grades one through nine were offered. Each year thereafter, another grade was added until the twelfth grade was included. The school’s staff consisted of a principal and sixteen classroom teachers. One four-room brick building was used as the office and as the main high school classroom building. Other buildings consisted of one-, two-, and three-room frame structures brought in from school sites involved in the consolidation. The first class to graduate from Lincoln High (1953) had seven members: Janice Harris, Ruby Jean Alston, Earnestine Williams, Maxie Williams, Mary Maxwell, Martha Maxwell, and Loisteen Scott.

Lincoln High went from having no accreditation in 1949 to a “B” accreditation by the Arkansas Department of Education in 1958. A lack of instructional materials and supplies, library resources, science equipment, and home economics furnishings kept the school from getting an “A” accreditation. Even with these shortcomings, a good instructional program was provided. Almost half of the instructional staff had earned advanced degrees from major universities.

The high school curriculum was general studies, consisting mostly of college preparatory classes. Most of the teachers were given dual responsibilities; for example, the basketball and track coach also taught science and physical education; the English teacher served as librarian; the commercial teacher was also the school secretary; an elementary teacher also taught music; and the social studies teacher was the choir director. There were several extracurricular activities available to students, such as choir, dramatics, agriculture, intramural sports, student council, a business club, and home economics clubs.

The majority of Lincoln’s students came from rural and farm families. Many parents would keep their children out of school during the fall to harvest their crops, which caused a drastic decrease in school enrollment. A split-session school year was developed to solve this problem: the school year began in July and continued through August, discontinued in September and October to allow for the harvesting of the crops, resumed in November, and ended in May. This practice was discontinued after a few years.

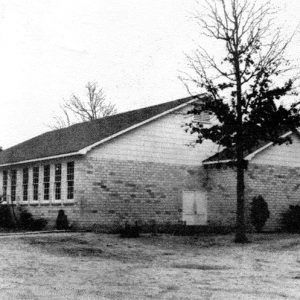

As the years at Lincoln passed, there were visible signs of progress. In 1953, a gymnasium (also used as an auditorium) was completed on campus. Two years later, teachers Eddie Dickens and Helen Williams wrote the school song. In 1958, the first counselor for the Lincoln High School student body was hired, and a student handbook was developed by faculty and student representatives. In 1960, a new red-brick, eight-classroom elementary building was constructed, and, in 1963, Lincoln organized its first marching band, under the direction of Elmarice Carlton.

In 1965, a gradual integration process was started in the Star City public schools as part of the federal government’s “Freedom of Choice Plan.” Nineteen black students chose to attend the all-white Star City High School, while no white students chose to attend Lincoln High. In 1966, the Lincoln High faculty was integrated when four white teachers were assigned to teach at the all-black high school.

A new brick cafeteria/auditorium was constructed in 1967. The Lincoln High Pirates, under the direction of Coach Sylvania Holt, were a track team consisting of Jerry Gragg, Dwight Gragg, Alvin Carroll, Floyd Dunn, Archie Dolls, Robert Trotter, George Wimberley, Cleo Ford, Henry Jordan, Leroy Everett, Clarence Baker, Rickey Kelly, Wilford DeBruce, and Sam Williams; they were district 6-B track champions in 1968. The basketball team also won first place in its district and went to the state tournament in its division.

The last class, consisting of twenty-five students, graduated from Lincoln High in 1970, and the school was also assigned its first white principal. The 1970–71 school year began with an integrated student body and instructional staff. Lincoln became Star City Middle School, offering education for all students in grades six through eight residing in the Star City School District. All students in grades nine through twelve were assigned to the previously all-white Star City High School. In the twenty-one years of Lincoln’s existence as an all-black school, it had four principals: Ruth Teal (1949–1954), Fulton Walker (1954–1965), Samuel Lambert (1965–1969), and Ray Wynn (1970), Lincoln’s first white principal.

For additional information:

History of Lincoln County, Arkansas, 1871–1983. Dallas, TX: Taylor Publishing Company, 1983.

“Star City Board Will Meet Negroes Seeking Integration.” Arkansas Gazette, July 17, 1964, p. 1B.

Alvin R. Carroll

Joliet, Illinois

Fulton Walker

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

Education, Elementary and Secondary

Education, Elementary and Secondary World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Lincoln High School

Lincoln High School

I was valedictorian of the graduating class of 1955. At Lincoln High School, there were many things we did not have, but we had teachers who loved and cared for the students. This meant so much to the students.

I was one of the first nineteen students who went to the white school in the fall of 1965. Stress was heavy on us as we quickly learned to depend on each other for support. I commend the entire administrative staff and teachers of Star City schools for making preparations for this important move. The Lincoln school staff also had done a good job of preparing us as students to be worthy of this challenge. All of the nineteen have moved on and contributed greatly in life, becoming dentists, lawyers, writers, skilled tradesmen, teachers, and other productive citizens of the community. I often reflect on my experiences being an integral part of the nineteen.

(2017) I didn’t think about it at the time, but looking back I can say I’m proud to have been one of the first nineteen black students to set foot on the SCHS campus in 1965. I admit that I tried to talk my folks out of sending me, but they’d have none of it because they were looking long range at what would be best for me and my life after graduating. Imagine being one of two black students in the 7th grade; midway through the first year, I suddenly became the only one. Times were so different then, and I credit both the white and black parents for being cooperative and supportive of that ground-breaking effort. I occasionally still communicate with a few of my former classmates: Debra Riley, Cliff Petty, Randall Huntley, James Chastain, and a few others. In 2021, there’s going to be a 50th reunion and I’m hoping that I and some of my other Lincoln High groundbreakers will make it.

This is an excellent article–very informative and very detailed. It is great to hear about how people really stuck together and helped wherever needed, with teachers performing double duty like teaching and other duties as assigned. I love the fact that the school at times had the school year split so children could help their families with work in the fields. I’m sure because of the sacrifices of others, some of the students became very productive citizens.