calsfoundation@cals.org

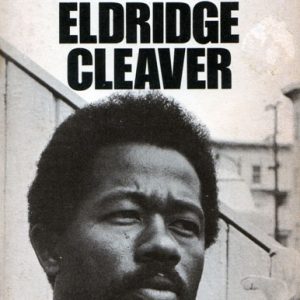

Leroy Eldridge Cleaver (1935–1998)

Leroy Eldridge Cleaver was one of the best-known and most recognizable symbols of African American rebellion in the 1960s as a leader of the Black Panther Party and the Black power movement. In the 1970s, he became a born-again Christian and later an active member of the Republican Party.

Eldridge Cleaver was born on August 31, 1935, in Wabbaseka (Jefferson County). His father, Leroy Cleaver, was a nightclub entertainer and waiter; his mother, Thelma Hattie Robinson Cleaver, taught elementary school. Many accounts portray Leroy Cleaver as a violent man who beat his wife. Eldridge Cleaver recalled those beatings as the beginning of his “ambition to grow up tall and strong, like my daddy, but bigger and stronger than he, so I could beat him to the ground the way he beat my mother.”

When Leroy Cleaver got a job in the dining car of a train that ran between Chicago, Illinois, and Los Angeles, California, in 1943, the family moved from Arkansas—first to Phoenix, Arizona, and finally to the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles in 1946.

In Los Angeles, Eldridge Cleaver was repeatedly in legal trouble, including arrests for bicycle theft and selling marijuana. In 1954, he was sent to the California State Prison at Soledad after being convicted of marijuana possession. After his release in 1957, he was convicted of assault with intent to murder and was incarcerated at San Quentin and then Folsom prison.

In the early 1960s, he joined the Black Muslim movement founded by Elijah Muhammad. Cleaver denounced the Muslim faith after the 1965 assassination of Malcolm X but was determined to put into place Malcolm’s dream of the Organization for African Unity.

After his release from prison in December 1966, he became a staff writer for Ramparts magazine and soon met the leaders of the newly formed Black Panther Party, including Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. After witnessing a successful Black Panther showdown with police at the Ramparts offices, Cleaver joined the Black Panther Party, believing Newton to be the successor to Malcolm X. After Newton’s arrest in March 1967 following a confrontation with Oakland, California, police, Cleaver, the party’s Minister of Information, led the “Free Huey” movement that brought fame to both Cleaver and the party.

Cleaver married Kathleen Neal in December 1967; they had two children and divorced in 1987.

Cleaver was wounded and arrested on April 6, 1968, in a Black Panther shootout with police also involving Arkansan Bobby James Hutton, who was killed. After a judge ordered Cleaver released from prison two months later, Cleaver undertook a series of lectures at the University of California at Berkeley and ran for president as the candidate of the Peace and Freedom Party. After attempts by Governor Ronald Reagan to stop Cleaver from speaking at Berkeley led to Cleaver’s speaking out against Reagan personally, his parole was revoked, and Cleaver was ordered back to prison. On November 24, 1968, three days before he was due to turn himself in, Cleaver fled and escaped to Cuba.

A few months later, Cleaver was granted asylum in Algeria. His wife joined him there, where they remained until moving to Paris in 1972. While living in Paris, Cleaver converted to Christianity and became motivated to return to the United States. After his 1975 return, Cleaver spent eight months in jail and performed community service to clear the legal obligations stemming from the 1968 shootout.

Cleaver published several books, including the autobiographical titles Soul on Ice (1968) and Soul on Fire (1978), Eldridge Cleaver: Post-Prison Writings and Speeches (1969), and Eldridge Cleaver’s Black Papers (1969).

In 1980, Cleaver attempted to create a new religion, Christlam, which was a combination of Christianity and Islam. In the early 1980s, he joined the Republican Party and endorsed Ronald Reagan in his 1984 presidential reelection campaign. He made several runs for political office between 1984 and 1992, including an unsuccessful candidacy for the Republican nomination in the 1986 U.S. Senate race in California. Cleaver had several drug-related arrests in the late 1980s and early 1990s but kicked his drug habit and rededicated himself to Christianity. When former colleagues questioned his numerous religious conversions and drastically changing political views, Cleaver said, “I have a very good track record of being ahead of other people in understanding certain truths and taking political positions far in advance of the crowd and turn out to be vindicated by subsequent experience. Yet, when I take these experiences, I have been attacked for doing so.”

Cleaver died on May 1, 1998, in Pomona, California, of undisclosed causes. At the time of his death, he was employed by the University of La Verne in La Verne, California, as a diversity consultant. He is buried in Altadena, California.

For additional information:

Cleaver, Eldridge. Soul on Fire. Waco, Texas: Word Books, 1978.

———. Soul on Ice. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1968.

———. Target Zero: A Life in Writing. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

Gifford, Justin. Revolution or Death: The Life of Eldridge Cleaver. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2020.

Lavelle, Ashley. “From Soul on Ice to Soul for Hire: The Political Transformation of Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver.” Race & Class 54 (October–December 2012): 55–74.

Manditch-Prottas, Zachary. “Meeting at the Watchtower: Eldridge Cleaver, James Baldwin’s No Name in the Street, and Racializing Homophobic Vernacular.” African American Review 52 (Summer 2019): 179–195.

Malloy, Sean L. “Uptight in Babylon: Eldridge Cleaver’s Cold War.” Diplomatic History 37 (June 2013): 538–571.

Rout, Kathleen. Eldridge Cleaver. Boston: G. K. Hall & Co., 1991.

Jeff Bailey

Arkansas State University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.