calsfoundation@cals.org

John Henry Harrison (Lawsuits Relating to the Lynching of)

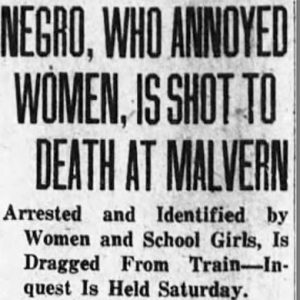

On February 3, 1922, an African American man named John Henry Harrison was lynched in Malvern (Hot Spring County) for allegedly harassing white women and girls. He had been arrested, taken to his victims for identification, and then jailed. Sheriff D. S. Bray, fearing mob violence, decided to take Harrison to the jail in Arkadelphia (Clark County) for safekeeping. Finding the roads out of town intentionally blocked by cars, he decided to travel by train instead. Bray, Harrison, and two deputies (S. J. Leiper and W. T. Gammel) boarded the train around 10:30 p.m., and Harrison was hidden under the seat in the “negro car.” According to the Malvern Daily Record, just as the train was beginning to leave, a masked man boarded and held the engineer at gunpoint. A masked mob of around twenty men detained the train until it could be searched. Finding Harrison, they shot him at least seventeen times. In an unusual move, Harrison’s sister, Callie Henry, later filed several suits in federal court against authorities and members of the mob.

The first laws providing for civil and criminal penalties for lynching were passed by Congress in 1870, 1871, and 1875. Intended to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment in reaction to widespread Ku Klux Klan activity, these Enforcement Acts held that discrimination against African Americans was a denial of constitutional rights and gave victims’ families the right to sue in federal court if state authorities failed to enforce the law and violence resulted. In 1883, however, these statutes were nullified by a number of U.S. Supreme Court decisions. However, a law passed in Georgia in 1893 permitted sheriffs to form posses to fight lynching, and two years later the state made it a criminal offense to interfere with law enforcement officials who attempted to break up mobs. That same year, North Carolina made it illegal to break into a prison and kill or injure a prisoner, a crime punishable with a fine of $500 and fifteen years in jail. In South Carolina, the 1895 state constitution prohibited mobs from removing prisoners from a sheriff’s custody. A number of other states followed, including Ohio (1896), Tennessee (1897), Kentucky (1897), Texas (1897), Indiana (1899), and Michigan (1899). Unfortunately, most of these state laws were vaguely worded; offenders were rarely indicted, and if they were put on trial, juries refused to convict them. In 1909, the Arkansas General Assembly passed Act 258; ostensibly intended to prevent lynching, the law did not punish members of mobs and did not contain penalties for officials who failed to protect prisoners but, instead, expedited trials of suspects who might face a lynching.

Although these laws were in force, it was rare for anyone to be tried and convicted. In her 2019 master’s thesis, Lacy A. Brown-Bernal lists a number of cases that came to trial, most of which were unsuccessful. Many such suits, like Callie Henry’s, relied on the idea that the man was the breadwinner in the family and that families could not survive if the breadwinner were killed. There were, however, a few cases that were decided in the plaintiff’s favor. In 1897, Charles Mitchell was lynched in Urbana, Ohio, despite being defended by the Ohio National Guard. His sisters Daisy Paine and Lillian Brown were successful in their suit for damages, receiving $1,250 each. On August 23, 1917, a minister, W. T. Sims, was lynched in York County, South Carolina, for “making reckless statements about the war.” His wife, Mary, sued for $2,000 and, after the third trial, was awarded the full amount.

It was in this legal context that Callie Henry filed her suit. There are scant details on the Henry and Harrison families. In 1920, Callie Henry, age thirty-one, was living in Fenter Township (Hot Spring County) with her husband, John Henry. John worked at the waterworks, and the couple had two children: Louis (age fourteen) and Addie (eleven). Living with them was John Harrison (thirty-nine), identified as John Henry’s stepbrother, and his four children: Martha (fourteen), Minnie (eleven), Joe (seven), and Rose (three).

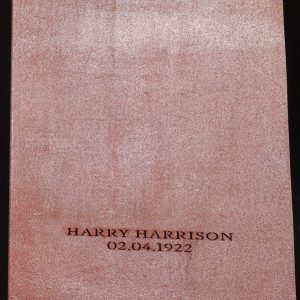

Public records include a little more information on the Henrys. In December 1918, John Henry, then forty years of age, married Callie Adkason in Pulaski County. It is possible that he was the John Henry who died from a gunshot wound in Pulaski County in October 1921. If so, this would have left John Harrison to support the family. John Henry Harrison, then thirty-three, registered for the World War I draft on September 12, 1918. At the time, he was living in Malvern and stacking lumber for the Wisconsin and Arkansas Lumber Company. His nearest relatives were listed as Martha, Millie, Rosa, Jewell, and Lucille Harrison. His death certificate, attested to by Callie Atkinson, noted that he died from “gunshot wounds from unknown parties (mob).” He was buried in the Masonic and Odd Fellows Cemetery in Malvern.

Although John Harrison was murdered in February 1922, Callie Henry did not file suit until October 23, 1923, when she was living in Missouri. She filed two suits in the District Court of the United States, one against law enforcement officials and the other against alleged members of the mob. The first suit named S. H. Leiper, W. T. Gamble (in error—it should have been Gammel), D. S. Bray, and W. H. Cooper, seeking damages for herself and for her “next friends” Martha, Millie, and Rose Harrison (who, in contradiction to census records, were identified as the sisters, not the daughters, of John Harrison). Her claim was that the girls were John Harrison’s sole legal heirs and that he was the sole support of the family.

Daniel S. Bray was the sheriff of Hot Spring County at the time of Harrison’s murder. In 1900, he was twenty-four and living and farming in DeRoche Township (Hot Spring County). Over the next nineteen years, he served as circuit clerk, a county worker in a “private court,” and a deputy sheriff. He began his duties as sheriff in 1919 and held the post until 1923. S. H. (Samuel Harper) Leiper was born around 1875 and, in 1900, was living in Malvern and working at a bottling works. By 1910, he was the manager of the ice plant in Malvern, and the 1920 census lists him as a lawyer. He died in 1954, and his obituary in the Malvern Daily Record indicates that he was a pioneer settler of Malvern, moving there when he was three with his schoolteacher father. At one time, he apparently owned extensive property in the city.

W. T. Gamble was probably the William T. Gammel who in 1900, at age eighteen, was living with parents Billie and Sue Gammel in Fenter Township and working as a farm laborer. He remained there in 1920. By 1922, he was not only a sheriff’s deputy but also the mayor of Malvern. In 1923, he moved to El Dorado (Union County), where he lived for the rest of his life. W. H. (William Howell) Cooper Jr. held the bond for Sheriff Bray in 1922. He was born in 1878 or 1879, and in 1910 he was living in Malvern with parents William H. and Sallie T. Cooper, working as a hardware merchant, probably in his father’s hardware store. He was still single and living with them in 1920.

Henry’s suit against Bray et al. alleged that Sheriff Bray “without cause, without a warrant or just complaint” arrested John Henry Harrison and jailed him in Malvern. She alleged that he was in jail for six or seven hours and “not permitted to make bond, nor to see his friends, who desired to look after his welfare.” She also alleged that “an intense feeling of hatred existed against the said John Harrison on account of some imaginary wrong he was supposed to have committed,” and there had been many threatening to lynch him.

According to her suit, Bray and Gammel “unwisely” decided to move him to the railroad station. When they arrived at the station, a large mob was present; nonetheless, they handed him over to Deputy Leiper, who hid him in a railway car. Mob members entered the car and took Harrison “without protest from the defendant Leiper and without any efforts on his part to protect him or shield him in any way.” Henry alleged that “by reason of the negligent conduct and willful neglect of their official duty of defendants Gammel, Leiper and Bray…the said John Harrison was unlawfully killed and murdered.” She claimed that Harrison was a manual laborer, could earn $5 a day, and gave it all to the plaintiffs, with whom he lived. She asked that $10,000 be awarded to each plaintiff.

On November 8, the defendants responded to the charges. In their demurrer, they claimed that Henry and the girls were really citizens of Arkansas and had moved to St. Louis temporarily for the purpose of filing the suit. They claimed that Harrison was not single, that he had never supported them, and that none of the plaintiffs were actually related to him. Denying that they had unlawfully detained Harrison, they stated that he was lawfully arrested and that they did not prevent him from posting bond; indeed, they claimed, no one came forward to offer it. In addition, they claimed to have no knowledge of the mob. According to their account, Bray, becoming fearful for Harrison’s safety, moved him to the remote farm of Deputy Gammel, where he was kept until they took him to the railroad station a few minutes before the train was to arrive. Leiper went into the station to purchase tickets, and Gammel and Bray took Harrison through the back of the station and put him on the train from the west side. The train began to move, and then a person or persons unknown entered the train from the east side, overpowered Leiper, and seized Harrison, killing him “before the said Gammel and Bray could get to him to defend him.” The case was scheduled for trial in April 1924.

Also on October 23, 1923, Henry filed a suit against Clarence Chamberlain, R. S. Hodges, Leonard Stanley, and Ray Galina, accusing them of being members of the mob that lynched Harrison. According to census records, Clarence Carter Chamberlain was thirty-six at the time of the lynching. Having previously been a laborer at a planer mill, by 1920 he owned a furniture store. R. S. Hodges may be the Bob Hodges who was living in Malvern in 1920 and working as a contractor on the railroad. He would have been forty-two years old at the time of the lynching. Leonard Stanley was born in Malvern, and when he registered for the World War I draft he gave his permanent address as Malvern, but his employment as a laborer and taxi driver for the Arkansas Transfer Company in Little Rock (Pulaski County). In 1920, he was an army private stationed at Camp Pike, listed as twenty years old. He returned to Malvern, where he married Grace Blackard in 1923. There is little information on Ray Galina, whose last name may really be Galligher or Gallagher.

The defendants answered the charges on November 10, many of their assertions being similar to those used by Bray et al. They claimed that Henry and the girls had moved to St. Louis “not to settle there, but to transfer jurisdiction to the Federal courts.” They denied being members of the mob and said that the plaintiffs had in no way been injured and thus had no claim to $10,000 damages each. Their trial, too, was scheduled for late April 1924.

On November 3, 1923, the Richmond Planet commented on the twin lawsuits, saying that the plaintiffs hoped to create “favorable sentiment against mob violence and also to stimulate a willingness on the part of officials to the law to put forth their best efforts to protect prisoners” as required by the U.S. Constitution and many state laws. In conclusion, the article noted that “Various Negro organizations throughout the country are watching the progress of this case with great interest.”

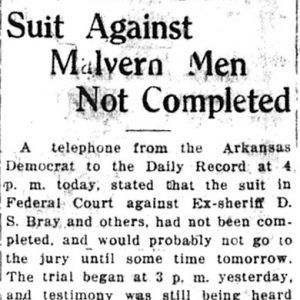

On April 29, 1924, Callie Henry filed papers to amend her plea for damages against Bray et al., now asking that she and the girls receive $5,000 compensatory damages plus $5,000 punitive damages “for their costs herein expended and for all other proper relief.” The case against Bray et al. was heard beginning at 3:00 p.m. the next day but continued on May 1 so that more witnesses could testify. On May 2, the Malvern Daily Record reported that the defendants had been acquitted, with the exception of Gammel, whose case was dismissed when Bray took full responsibility for the events surrounding the lynching. The report asserted that the verdict was no surprise, because Bray and his deputies had “always been known to use every effort to uphold the law.” It also noted, as above, that there was some involvement of “Negro organizations”: “it has always been known just where it originated, and what organization was behind it.” The report also noted that the separate case against the alleged mob members was continued until the October term of the court.

On September 7, 1925, the charges against Leonard Stanley were dismissed, and on September 29, Callie Henry again filed suit, asking for a judgment of $10,000 against each defendant. This time, the suit named alleged mob members Chamberlain, Hodges, Galina, and two additional people: Jack Potts and Joe Ledsinger. Ledsinger (referred to in most records as Letsinger) was living in Malvern in 1920 and working as a foreman at a sawmill. His full name was Joseph E. Letsinger, and he would have been forty years old at the time of the lynching. Jack Potts’s full name was David Jackson Potts. In 1910, he was living in Malvern and working for a steel company. When he registered for the draft in 1918, he listed his permanent address as Malvern, but he was employed as a foreman at Pratt Engineering and Machine Company in Little Rock. In 1920, he was working as a foreman on a highway crew in Conway County, but he must have returned to Malvern soon after this. In 1930, he was living there and working as a foreman at a gravel company. He died in Malvern in 1930. He would have been forty-nine at the time of Harrison’s lynching.

When she filed suit on September 29, Henry petitioned to file as a poor person, asking that she not be liable for costs and claiming that she had no property, no money besides what she earned as a common laborer, and no assets with which to pay. On October 14, Potts and Letsinger replied, claiming that Henry’s suit showed no cause of action and was barred by the statute of limitations. On January 12, 1926, the case against Potts and Letsinger was dismissed, and in March the case against the others was dismissed at the cost of the plaintiffs.

Confirming reports that “Negro organizations” had been involved in the Henry case, an article in the May 1925 issue of The Crisis magazine commented on the Harrison case. The report claimed that after Harrison was lynched, he was “found…to be entirely innocent.” Witnesses at the lynching had recognized some members of the mob, which was the basis of Henry’s suit. According to The Crisis, “Mrs. Henry sold her little home and paid all she received to her lawyers to provide for necessary court costs….Having no funds Mrs. Henry appealed to the NAACP to pay the balance necessary in gathering witnesses, printing briefs and records, and other court costs in the suit for damages.” The national office subsequently contributed $250 toward her costs, motivated in part by an appeal from Little Rock attorney Scipio Jones. The Crisis went on to declare: “Awarding of damages in such a case would have a salutary effect in checking lynching not only in Arkansas but in other parts of the country.”

After a complicated journey through the courts, Callie Henry’s legal battle proved fruitless. She apparently disappeared into obscurity, there being no public records for either Callie Henry or the Harrison children in ensuing years.

For additional information:

“The Bardwell Lynching.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 12, 1893, p. 3.

Brown-Bernal, Lacey A. “African American Women’s Resistance in the Aftermath of Lynching.” MA thesis, University of Texas at Arlington, 2019.

Carver, Danna K., and Gerald W. Williams. “The Lynching of John Henry Harrison.” The Heritage 49 (2022): 17–26.

“Civil Rights and the Federal Law: A Lecture Delivered by the Honorable Francis Biddle, Attorney General of the United States.” Cornell University, October 4, 1944.

“Negro Preacher Meets Death at Mob’s Hands.” Concord Times (North Carolina), August 27, 1917, p. 2.

“Negroes Lose Case against Malvern Men.” Malvern Daily Record, May 2, 1924, p. 1.

“Sisters of Slain Man File Suit.” Richmond Planet, November 3, 1923, p. 1.

“Suit against Malvern Men Not Completed.” Malvern Daily Record, May 1, 1924.

“Suit Based on Lynching of Negro Dismissed.” Arkansas Gazette, March 8, 1925.

“Three Important Cases.” The Crisis 30 (May 1926): 35–36.

“Two Citizens Killed.” New York Times, June 5, 1897, p. 1.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Law

Law John Henry Harrison Lynching Article

John Henry Harrison Lynching Article  Hot Spring County Lynching

Hot Spring County Lynching  Lynching Lawsuit Article

Lynching Lawsuit Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.