calsfoundation@cals.org

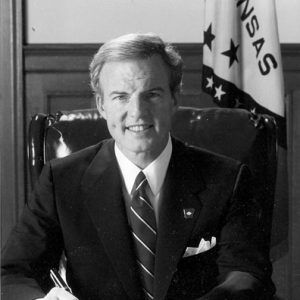

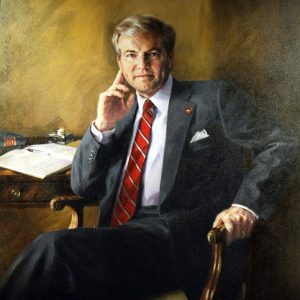

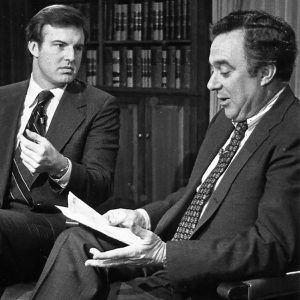

Jim Guy Tucker Jr. (1943–2025)

Forty-third Governor (1992–1996)

James Guy Tucker Jr., the forty-third governor of Arkansas, had a brief gubernatorial career that abruptly ended due to criminal conviction. His administration carried Arkansas from the end of the Bill Clinton administration, during which Tucker essentially acted as governor the last year because of Clinton’s campaigning for president, to the beginning of the Mike Huckabee gubernatorial administration, which remained in power long enough to be stopped only by term limits. In his personal life, Tucker weathered political challenges, survived health problems, and faced a criminal indictment.

Jim Guy Tucker was born on June 13, 1943, in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, to James Guy Tucker and Willie Maude White Tucker. His family moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County) when he was a child, and he was educated in public schools. He graduated from Harvard with a BA in government in 1964, after which he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps. Despite two appeals, Tucker was discharged for health reasons after three months. Stints in 1965 and 1967 in Vietnam as a civilian war correspondent became a source of exposure for Tucker as he recorded them in his book, Arkansas Men at War. After finishing work in Vietnam, Tucker returned to Arkansas to pursue a political career.

After receiving his law degree at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) in 1968, he became an associate attorney with the Little Rock firm Rose, Barron, Nash, Williamson, Carroll, and Clay (now known as the Rose Law Firm). He left in 1970 upon winning the race for prosecuting attorney for the Sixth Judicial District. He was twenty-seven and widely regarded as a wunderkind with a brilliant future. In 1972, he was elected to the first of two terms as state attorney general. On November 8, 1975, he married Betty Allen Alworth, who had two children from her previous marriage. The couple had two children together.

In 1976, he was elected to represent the Second Congressional District and was appointed to the House Ways and Means Committee, the Social Security Subcommittee, and the Speaker’s Task Force on Welfare Reform. The 1978 edition of the Almanac of American Politics predicted a promising future but suggested that his days in Congress might be shortened if he ran for the U.S. Senate that year, which he did. He ran a spirited campaign for John McClellan’s vacated Senate seat but lost to the enormously popular governor David Pryor in the Democratic primary.

After eight years in public office, he returned to private law practice in 1979 and became a partner in the Tucker and Stafford firm. In 1982, he attempted a political comeback, running for governor in the Democratic primary, but came in third in a five-man race as Clinton reclaimed the seat he had given up to Frank White in 1980. Tucker’s political career seemed truly over. From 1982 until October 1991, he practiced law as a senior partner in the Mitchell, Williams, Selig, and Tucker firm. His specialty was corporate and commercial litigation, and he wrote and published articles in The Arkansas Banker and State Government Quarterly. He also began to engage in business enterprises, including real estate and condominium development. In 1983, he formed County Cable Limited Partnership with his wife, and the company provided cable TV service in rural Pulaski County. From modest beginnings, he expanded his cable TV operations to other areas of the country and acquired interests in cable companies in Texas, Florida, and Great Britain. In 1988, he traded County Cable to Falcon Cable Media of California in return for a Falcon Cable operation near Dallas, Texas.

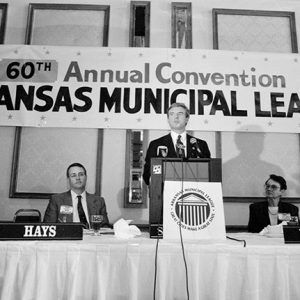

Despite success in his law practice and his cable business, Tucker yearned for political office. In 1990, Tucker prepared for another run for governor. When Clinton announced his reelection bid, Tucker opted instead to run for lieutenant governor. Clinton and Tucker won their races handily. The lieutenant governor’s post paid only $14,000 and did not hold the power or the prestige of the governor’s office, but Tucker quickly found himself dealing with more authority. Once Clinton began to campaign for the presidency in earnest in 1991, Tucker became acting governor, and upon Clinton’s resignation in December 1992, Tucker became governor. In November 1994, he garnered sixty percent of the vote to win the office and seemed poised to fulfill his ambitions.

Even as acting governor, Tucker exemplified the tendency for decisiveness that he had first shown as a young prosecuting attorney and later as attorney general. In one particular case, Tucker called a special session of the legislature to address a shortfall in Medicaid funding, the result of which was increased taxes.

Early in his public career, Tucker expressed reservations about the death penalty but later changed his mind. After assuming the governor’s office in December 1992, he supported prison reforms, including more stringent sentencing guidelines and indicated that he was willing to consider eliminating “good time” paroles. Ironically, it was over the pardoning of certain African American convicts while Tucker was out of state that his governorship experienced its first real controversy. While Tucker was in Washington DC attending Clinton’s inauguration in 1993, acting governor Jerry Jewell pardoned two convicts and extended executive clemency to three others. Tucker returned to a media circus and a public uproar. Expressing surprise at Jewell’s actions, he called for limits on actions by acting governors, and legislators introduced a spate of bills to curb the power of acting governors and limit executive clemency. Within ten days of returning to the state after the Jewell pardons, Tucker signed a clemency and pardon delay law, which required a thirty-day notice on all such actions.

In his first regular legislative session as governor, Tucker promoted a particularly conservative approach to spending. Rather than raise taxes again, he cut the budgets of agencies that could generate their own revenue to offset reduced allocations. Tucker used this model to allocate more budget money to public education by reducing the budgets of agencies such as the Department of Parks and Tourism, which began charging entry fees to state parks.

When Tucker called a special legislative session in August 1994 to deal with the rising crime rate among juveniles, he raised the concerns of children’s rights activists. His critics said the bills he sponsored were designed to facilitate the apprehension and punishment of juvenile defenders rather than focusing on prevention. Nevertheless, at the end of the session, he signed thirty-one bills into law, including one that allowed minors to waive their right to counsel without consulting their parents. Other measures addressed the confidentiality of certain juvenile offenders, the seizure and forfeiture of firearms found in the unlawful possession of minors, and the removal of the $2,000 cap on the amount a juvenile might be required to pay as restitution. One measure approved by the General Assembly provided for an increase in the penalty for the unlawful possession of a firearm by a minor. Although the session had been called to address juvenile crime, the legislature also turned its attention to adult crime and passed a bill authorizing the purchase of an automated fingerprinting system for adult and juvenile offenders.

By the end of 1994, Tucker had emerged from Clinton’s shadow. In November, he won a four-year term against Republican Sheffield Nelson. But the next two years presented challenges. He was neither able to persuade voters to approve a procedure to rewrite the state’s constitution, nor to pass a $3.5 billion highway bond construction program.

Again his ambitions were frustrated when he became caught up in the Whitewater investigation surrounding Bill Clinton. On May 28, 1996, he was convicted for misapplying funds for a $150,000 bank loan. The next day, he announced that he would step down as governor, even as he continued to protest his innocence. After briefly rescinding his resignation, he left office on July 15, 1996. He reentered the private sector to focus on his business enterprises.

In 1996, Tucker was placed on a liver transplant waiting list (he had been diagnosed in 1984 with primary sclerosing cholangitis, which leads to blockage of the bile ducts). On Christmas Day, he received a transplant, which probably saved his life and kept him out of prison—he was sentenced to probation. Despite complications, the transplant restored his health. Tucker served his probation and repaid the $150,000 loan.

Tucker donated his papers to the University of Arkansas at Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture in 2012. They cover all aspects of his public life as attorney general, congressman, lieutenant governor, and governor.

Tucker died in Little Rock on February 13, 2025, after having entered hospice the previous month. He was buried at Mount Holly Cemetery.

For additional information:

Bowden, Bill. “Tucker, Former Governor, Congressman, Dies at 81.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, February 14, 2025, pp. 1A, 6A–7A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2025/feb/13/former-gov-jim-guy-tucker-dies-at-age-81/ (accessed February 14, 2025).

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Dumas, Ernest. “A Charismatic Lawyer: Former Arkansas Gov. Jim Guy Tucker Dies at Age 81.” Arkansas Times, March 2025, pp. 25–29. Online at https://arktimes.com/arkansas-blog/2025/02/13/former-arkansas-gov-jim-guy-tucker-dies-at-age-81 (accessed February 13, 2025).

———. “Governor Tucker.” Arkansas Times, January 1992, pp. 46–49, 57–58.

English, Arthur. “The Political Style of Jim Guy Tucker.” Comparative State Politics 18 (April 1997): 18–28.

Jim Guy Tucker Papers. Center for Arkansas History and Culture. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Lockwood, Frank E. “Jim Guy Tucker Laid to Rest.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, February 25, 2025, pp. 1B, 3B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2025/feb/24/former-arkansas-gov-jim-guy-tucker-eulogized-as/ (accessed February 25, 2025).

Jeannie M. Whayne

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.