calsfoundation@cals.org

Jim and Jack Ware (Lynching of)

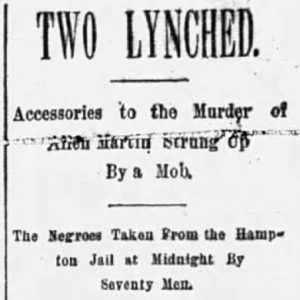

On July 14, 1895, brothers Jim and Jack Ware, who allegedly assisted Wiley Bunn in the murder of Allen Martin, were lynched in Hampton (Calhoun County).

The Ware family had been living in Calhoun County for some time. In 1870, Moses and Easter Ware were living in Jackson Township. Among their children were two sons, fifteen-year-old James (Jim) Ware and thirteen-year-old Jack. Moses and James Ware were working as laborers. They were still in Jackson Township in 1880. Jack, along with James and James’s wife, Susan, were still living with their parents. Moses was farming, and both James and John were working as laborers.

In 1880, fourteen-year-old Willey (Wiley) Bunn was living in Jackson Township with his parents, Drew and Sallie Bunn, and four siblings. Drew and all of the older children were working as laborers. Willey could neither read nor write. According to Arkansas marriage records, Wiley Bunn married Amanda Juniel in 1887.

The murder victim’s full name was James Allen Martin. In 1880, he was thirty-three years old, a farmer, and living in Jackson Township with his wife, Lucinda, and daughter Martha. Martin died on July 2, 1895. Two weeks later, the Arkansas Gazette reported that he had been ambushed by Wiley Bunn, who then escaped. The conflict leading to the attack apparently grew out of the recent election of school directors in Hampton. Martin, who was white, and Bunn, who was African American, were running against each other; when Martin won, Bunn was incensed. Bunn then allegedly borrowed Jack Ware’s gun to go hunting but instead used it to murder Martin. Even though Jack had only lent the gun, and “there was hardly any [evidence] against the other negro [Jim Ware],” the circuit court was in session, and the brothers were arraigned and jailed to await trial.

On Friday, July 12, a crowd gathered outside the jail, but Judge Charles W. Smith, Colonel H. P. Smead, and Colonel J. R. Thornton persuaded them not to lynch the brothers. A crowd of between fifty and seventy men gathered the following night, and despite the pleas of the prosecuting attorney, the Ware brothers were hanged. The San Francisco Call reported that members of the mob “were not masked and made no effort in any way to conceal their identity. All was quiet this morning.” According to the Gazette, “Prominent men in the county were engaged in the mob, but the action…is condemned by all law-abiding citizens.”

On July 8, a girl named Alice Martin of Summerville in Hampton Township wrote a letter to her uncle Sanders Martin that gives more details about the crime. Alice was the daughter of Allen Martin’s brother, Chesley B. Martin, and was writing to another of Allen’s brothers, Dink Sanders Martin. According to Alice, on July 2, Allen Martin stopped to let his horse drink as he was returning from one of his fields. While he was there, “Wily [sic] Bunn was [behind] some bushes & shot him down.” According to Alice, Martin had been shot several times in the head, including through one eye. He was still alive when his daughter Dora found him, but he died a short time later without speaking. Alice reports that Wiley Bunn had escaped but that Moses Ware’s oldest son had given Bunn the gun, and he was in jail. She also claimed that Wiley Bunn had been living on Martin’s place for nearly six years.

There may have been another accessory to Martin’s murder. In a case published in the Southwestern Reporter in 1902, an African American named John Dickson or Dickinson (the report uses both names) appealed his extradition back to Arkansas from the Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). According to the summary of the case, on June 16, 1895, Dickson was indicted in Calhoun County for inciting and abetting Wiley Bunn (called in this case Wiley Brown) in Allen Martin’s murder. Although he denied any involvement in the crime, knew nothing about it, and was not present when the crime was committed, Dickson was jailed for three weeks. After Jim and Jack Ware were hanged, Dickson was released and assumed there were no remaining charges against him. He moved to Indian Territory, and on November 4, 1899, Arkansas governor Daniel W. Jones asked for his extradition. Dickson appealed, asserting that “some fifteen or twenty other colored persons in said county were horribly beaten and bruised and mangled on account of the same charge for which his extradition is sought.” Dickson’s appeal included another allegation. He claimed that “another colored man was afterwards murdered and lynched by the deputy sheriff of Bradley county and others from Calhoun county.” There is no information available about any African-American named Wiley Brown who may have lived in Calhoun County, and no newspaper reported anything about the additional lynching.

Allen Martin’s wife, Lucinda (Lou), remained in Calhoun County after his death. In 1900, she was living there with five children, the youngest of whom, James A. Martin, was twelve years old. She died in 1921 and is buried with her husband in Ricks Cemetery near Hampton. Moses Ware’s first wife apparently died, and he married Georgeann Pickett on March 5, 1885. In 1900, they were living in Franklin Township of Calhoun County with six young children.

For additional information:

“Ex Parte Dickinson.” Southwestern Reporter, Vol. 69. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing, 1902.

McClinton, Edith W. Scars from a Lynching. Little Rock: Backyard Enterprises, 2000.

“Two Lynched.” Arkansas Gazette, July 16, 1895, p. 1.

“Two Negroes Lynched.” San Francisco Call, July 15, 1895, p. 3.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Ware Lynching Article

Ware Lynching Article

Jack and Jim Ware were my great-grandfather and uncle. My grandfather was Henry Carlton Ware, one of the sons of Jim (James) Ware. Papa (my grandfather) cried about this in his deathbed. I also knew my great-grandmother, the widow of James. I grew up down the street from my grandparents and visited “Grandma Mollie” at least once or twice a week. The story is quite different from what was reported. The town apparently went beserk afterward and went on a lynching spree. Shameful!!! My grandfather was in the first graduating class at Philander Smith College and was the first Black postmaster in Little Rock.

Mose Ware was my grandfather’s grandfather.

I am the great-great-granddaughter of Mose and Georgiana Ware. James and Jim would have been my great-great-uncles.

I’m the grandson of Jack Ware.