calsfoundation@cals.org

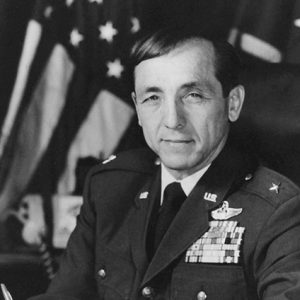

James Robinson Risner (1925–2013)

James Robinson (Robbie) Risner, a native of Mammoth Spring (Fulton County), was a much-decorated fighter pilot famed for his resistance to his North Vietnamese captors as a prisoner of war during the Vietnam War.

Robbie Risner was born on January 16, 1925, in Mammoth Spring, the son of sharecroppers Grover W. Risner and Lora Grace Robinson Risner. He was the fifth of seven children. Risner apparently did not live in Arkansas for long, with census records showing the family living in Oak Grove, Missouri, in 1930, and in Tulsa, Oklahoma, by 1940.

Risner joined the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1943 at age eighteen and served in Panama during World War II, seeing no action, although he trained as a pilot. After the war, he joined the Oklahoma Air National Guard, which was federalized during the Korean War, during which Risner flew 108 missions in F-86 Sabrejets. He became an ace by shooting down eight enemy MiG fighters.

Risner was awarded the Silver Star for a September 15, 1952, action in which his wingman’s jet was damaged during fighting with enemy aircraft. Risner flew his aircraft behind his comrade’s crippled jet, nudging it forward with the nose of his plane in an attempt to help him to friendly territory. Wingman Joe Logan bailed out over water and became entangled in his parachute cords, however, drowning before rescuers could reach him.

During the Korean War, Risner was also awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross for his actions on August 5, 1952, receiving an Oak Leaf Cluster to that award for exploits on September 5, 1952, and a second Oak Leaf Cluster for heroism on January 21, 1953.

Following the war, in 1957, he was chosen to fly an F-100F Super Sabre to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of Charles Lindbergh’s ground-breaking transatlantic flight. Risner flew the Spirit of St. Louis II on Lindbergh’s same route, completing the flight in one-fifth of the time it took the earlier flier and establishing a new transatlantic record of six hours and thirty-seven minutes.

In Vietnam, Risner was struck by enemy fire on four out of five consecutive missions, and he was shot down over the Gulf of Tonkin in March 1965. He received the Air Force Cross for his actions with the Sixty-Seventh Tactical Fighter Squadron on April 3–4, 1965, and was awarded an Oak Leaf Cluster to his Korean War Silver Star for operations against the North Vietnamese between September 9 and 12, 1965. Time magazine featured him on the cover of its April 23, 1965, issue, which highlighted a dozen Americans serving in Vietnam.

On September 16, 1965, Risner was leading an attack on a North Vietnamese missile base when his jet was disabled, forcing him to bail out. He was captured and taken to the Hoa Lo Prison—dubbed the “Hanoi Hilton” by its American prisoners—where his captors waved the Time magazine in his face. As a lieutenant colonel, Risner was the highest-ranking prisoner at Hoa Lo for most of the nearly eight years he was there and was subjected to particularly brutal treatment, being held in a darkened, solitary cell for three years and shackled for weeks at a time.

Risner encouraged resistance among his fellow American captives, urging them to withstand their jailers’ torture but not to the point of suffering permanent physical or mental disability. When forced to make a statement against the war, he did so with mispronounced words and a heavy German accent, bringing further punishment from his captors.

Perhaps his greatest act of rebellion was the organization of a forbidden church service in 1971. As his jailers dragged him to another period of solitary confinement, he could hear his fellow prisoners break into “The Star-Spangled Banner.” “I felt like I was nine feet tall and could go bear hunting with a switch,” Risner said later. (In reference to that remark, the Air Force Academy at Colorado Springs, Colorado, dedicated a nine-foot-tall statue of Risner in 2001.)

He was among the first group of American prisoners released from captivity, on February 12, 1973, and pronounced himself ready to fly again “after three good meals and a good night’s sleep.” Risner received the Air Force Distinguished Service Medal and the POW Medal for his actions while in captivity. Other awards include the Bronze Star with “V” device and Oak Leaf Cluster, Air Medal with seven Oak Leaf Clusters, Joint Service Command Medal, and Purple Heart with three Oak Leaf Clusters.

Two years before he retired from the air force as a brigadier general in 1975, he published his memoir of his time as a prisoner of war, The Passing of the Night. In 1976, the Robbie Risner Award was created to recognize an air force weapons officer who makes the greatest combat impact in his or her first year after graduating from the Weapons Instructor Course at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada.

Risner’s first marriage ended in divorce. His second wife, Dorothy Risner, was the widow of an American soldier who died in the war. The couple raised their combined six children together.

Following the war, Risner raised quarter horses in Texas and became executive director of the Texans’ War Against Drugs. He was also appointed as a U.S. delegate to the Fortieth Session of the United Nations General Assembly by President Ronald Reagan. He would participate in reunions of airmen, and at one in the 1990s he met a Russian MiG pilot who had served in Korea. When the Russian wondered if they might have met in combat, Risner replied, “No, way. You wouldn’t be here.”

Risner died at his home in Bridgewater, Virginia, on October 22, 2013, following a series of strokes. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Section 55, Site 626.

For additional information:

“Brigadier Robinson Risner.” U.S. Air Force. http://www.af.mil/About-Us/Biographies/Display/Article/105823/brigadier-general-robinson-risner/ (accessed December 16, 2017).

Chawkins, Steve. “J. Robinson Risner Dies at 88; Leader of Hanoi Hilton Prisoners.” Los Angeles Times, October 30, 2013. Online at http://articles.latimes.com/2013/oct/30/local/la-me-robinson-risner-20131031 (accessed December 16, 2017).

Correll, John T. “Nine Feet Tall.” Air Force Magazine, February 2012, pp. 74–78.

Howes, Craig. Voices of the Vietnam POWs: Witnesses to Their Fight. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Martin, Douglas. “Robinson Risner, Ace Fighter Pilot, Dies at 88.” New York Times, October 28, 2013. Online at http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/28/us/robinson-risner-ace-fighter-pilot-dies-at-88.html?mcubz=3 (accessed December 16, 2017).

Risner, Robinson. The Passing of the Night. New York: Random House, 1973.

Schudel, Matt. “Robinson Risner, Air Force Ace and POW, Dies at 88.” Washington Post, October 29, 2013. Online at https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/robinson-risner-air-force-ace-and-pow-dies-at-88/2013/10/29/ec759f3e-40ae-11e3-a624-41d661b0bb78_story.html (accessed December 16, 2017).

Mark K. Christ

Little Rock, Arkansas

Aviation

Aviation Military

Military World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 James R. Risner

James R. Risner  James R. Risner

James R. Risner  James R. Risner Statue

James R. Risner Statue

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.