calsfoundation@cals.org

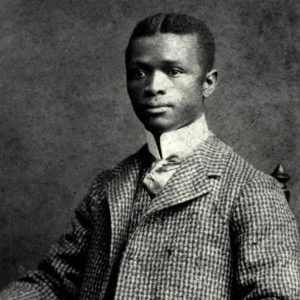

Isaac Fisher (1877–1957)

Isaac Fisher was a prominent African-American educator in the early part of the twentieth century. A protégé of famed black educator and leader Booker T. Washington, Fisher served as president of Branch Normal College (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff—UAPB) in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) from 1902 to 1911.

Isaac Fisher was born on January 18, 1877, on a plantation named Perry’s Place in East Carroll Parish, Louisiana. His parents were former slaves; little is known about them beyond the fact that they had sixteen children, the last of whom was Isaac. In 1882, the family was forced to live for six months in the plantation’s cotton gin following a levee break on the Mississippi River, an experience that left Fisher determined never to live close to the Mississippi again. Following the death of his mother in 1886, he went to Vicksburg, Mississippi, where he lived with an older sister. While he hoped to continue the limited formal schooling he had received in Louisiana, after one year in a Vicksburg school, he started working as a baker’s assistant and bread wagon driver. He then worked in a drug firm, a job that allowed him to read and study, efforts that were encouraged by his employers.

Around this same time, Fisher learned about Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute, and after numerous inquiries he set off for Alabama, where he worked his way through the school’s program, graduating as the valedictorian in 1898. With Washington’s support, Fisher secured a job teaching at the Schofield School, a Quaker school in Aiken, South Carolina. There, he also organized farmers’ conferences similar to those that were a staple of life at Tuskegee. In 1899, Washington asked him to take on the job of assistant northern financial agent for Tuskegee, which took him to New England to attempt to increase interest in the developing school. After two years in New England, Fisher’s request to return south was granted, with his new responsibilities including the organization of various farmers’ conferences that were an important part of Tuskegee Institute’s efforts. That same year, Fisher married a local Tuskegee woman, Sallie McCann; they had one daughter.

In early 1902, Fisher became principal of Swayne Public School in Montgomery, Alabama. Put forward for the position by Washington, he assumed the vacancy in the middle of the academic year. He was offered a chance to return the next year, but the invitation to continue at Swayne came the same day as an offer came from the University of Arkansas to assume the presidency of Branch Normal College. While he had not been an active candidate for the position, his name had again been put forth by Washington. The twenty-five-year-old Fisher opted for that post over the return to Swayne.

With a mission to train teachers, Branch Normal, the state’s second land grant institution, had been founded in 1873, and while the legislation that created it announced its mission as serving “the poorer classes,” from the beginning it was understood that it was the school intended to prepare the state’s black teachers. However, by the time Fisher arrived in 1902, the school was a clear victim of the established concept of “separate but equal.” Indeed, while technically the president of the college, Fisher had his authority deeply undermined by the fact that the state’s white power structure had taken over the financial control of the school. Further complicating his efforts were the attempts by the Arkansas General Assembly to allocate funds based on race and the vetoes of the school’s funding by Governor Jeff Davis. Too, Fisher and the school were the continuing objects of harassment by white officials determined to discredit both the school and its leadership. Fisher was able to implement parts of the Tuskegee curriculum, in particular an expansion of industrial training, but he was also in the difficult position of succeeding the school’s long-serving first president, Joseph Carter Corbin, who was popular with the faculty; Corbin was also an adherent to W. E. B. DuBois’s ideas about the education of African Americans, which conflicted with those of Washington. Undermined at almost every turn, after almost a decade of frustration, Fisher resigned in 1911.

Initially, Fisher remained in Pine Bluff, where he sold real estate and founded the Colored Young People’s Inspiration League. Then, in 1913, at Washington’s request, he returned to Tuskegee, where he helped with conference work and for a time served as editor of Tuskegee’s Negro Farmer. He left in 1916 and moved to Nashville, Tennessee, to assume the position of editor of the Fisk University News as well as all documents of the university. He also taught argumentation and journalism. In 1925, in the midst of a power struggle at Fisk, Fisher left the university.

That same year, he became the first African American to be awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, a grant he used to study world race relations. In 1929, Fisher became the General Secretary of the YMCA of Virginia’s Hampton Institute, where he also served as a contributing editor of its journal, Southern Workman. In 1934, he became the journal’s publication secretary and editor. In 1936, Fisher relocated to Florida, where he served as director of the Department of Research and Publications at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College, a post he held until 1942, when age and ill health forced his retirement. Throughout this time, he became an award-winning essayist who was much in demand as a speaker across the South.

Upon retirement, Fisher and his wife moved to Minnesota to be near their daughter, who was working in St. Paul. He died on August 23, 1957.

For additional information:

Fisher, Isaac. “A College President’s Story.” The Literature Network. Online at http://www.online-literature.com/booker-washington/tuskegee-and-its-people/6/ (accessed September 15, 2017).

“Isaac Fisher.” John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. http://www.gf.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Unfettered-and-Unrestrained.pdf (accessed September 15, 2017).

Wheeler, Elizabeth L. “Isaac Fisher: The Frustrations of a Negro Educator at Branch Normal College, 1902–1911.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 41 (Spring 1982): 3–50.

William H. Pruden III

Ravenscroft School

Isaac Fisher

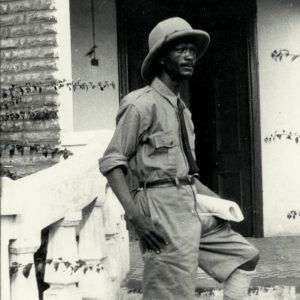

Isaac Fisher  Isaac Fisher in Africa

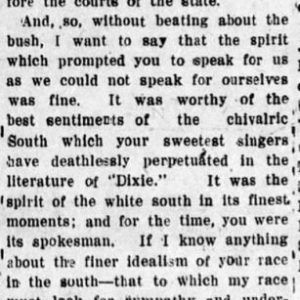

Isaac Fisher in Africa  Isaac Fisher Letter

Isaac Fisher Letter  UAPB Faculty

UAPB Faculty

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.