calsfoundation@cals.org

Huntsville (Madison County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 36º05’10″N 093º44’28″W |

| Elevation: | 1,449 feet |

| Area: | 5.38 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 2,879 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporated: | July 16, 1925 |

Historical population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

224 |

312 |

362 |

– |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

– |

– |

602 |

776 |

1,010 |

1,050 |

1,287 |

1,394 |

1,605 |

1,931 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2,346 |

2,879 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Huntsville is the seat of Madison County, a rural county in the Arkansas Ozarks.

Pre-European Exploration

The area which is now Huntsville has been inhabited at least 10,000 years. Early inhabitants lived in the White River lowlands, farming there and building some mound centers; the upland shelters served as storage areas, burial sites, and temporary camps. Artifacts of the Mississippian culture have been found at the Huntsville Mounds, an archaeological site near the town. By the historic period, all of what is now Madison County was part of the Osage hunting grounds. Treaties in 1808 and 1825 ceded Osage interest in these lands to the United States. The signature of Hurachais, the War Eagle, appears on the 1825 treaty; he is commonly thought to have been the Osage leader in the Huntsville area, and a local creek and township are named after him.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Explorers from Alabama came to what is now Huntsville in 1827. It was named after their hometown, though most local settlers were from Tennessee. Madison County was established in 1836, and it was clear that Huntsville would be the county seat. The first courthouse was built there in 1837, in the central town square. The town was also surveyed in that year by county surveyor Thomas McCuistion (who also served as a schoolmaster at one of the county’s earliest schools just outside Huntsville). John Buchanan, the only postmaster in the region, moved his post office to the town at that time, along with his home. He attempted to change the name of the town to Sevierville, in recognition of Ambrose Sevier, but was not successful. The post office was officially named Huntsville on January 17, 1840.

The Trail of Tears passed through Huntsville, with Native Americans heading from Alabama to Oklahoma in the course of what was then known as Indian Removal.

By the early 1840s, Huntsville had two stores, a blacksmith, and a hotel, and growth continued until the outbreak of the Civil War, at which time there were numerous stores, saloons, blacksmiths, saddlers, mills, stables, lawyers, and a newspaper. Isaac Murphy, later to be the eighth governor of Arkansas, settled in Huntsville in 1854. A girls’ school was opened just south of Huntsville in 1857. Methodist and Presbyterian churches found homes in Huntsville. The town was a center for business and entertainment for the agricultural communities surrounding it, and a convenient stopping point for travelers.

Civil War through Reconstruction

No battles took place in Huntsville, but the Civil War had a profound effect on the town. Several battalions were mustered in Huntsville, and soldiers from both armies were garrisoned there as they passed through. Since the sympathies of the people of Madison County were divided and the area was not under control of either army, guerillas were very active in the region. Many lives were lost, and the town’s economy was essentially destroyed.

One incident, known as “the Huntsville Massacre,” took place in the town on January 10, 1863. The Union army under General Francis J. Herron executed nine prisoners of war. A letter from Colonel C. W. Marsh referred to this as “murder” and “a great outrage.” Most of these men were buried in Huntsville. In November of the same year, Union forces traveled through the area, killing and capturing guerillas. In September of 1864, there was a skirmish at Rodger’s Crossing outside of Huntsville.

The first courthouse, and much of the rest of the town, burned down during the Civil War. Most businesses were closed, the newspaper shut down, and normal life was suspended. Following the war, the remaining residents began to rebuild their lives and businesses. Former slaves remained in the area, with the African-American population growing until the twentieth century.

The first public school district in Madison County was the Huntsville district, established in 1868. A number of newspapers began publication during this period, though none lasted long.

In many ways, life in Huntsville after the Civil War was a matter of rebuilding to the point at which they had been before the war. The timber industry became central to the local economy, but otherwise, subsistence farming of the pioneer variety was the rule. Huntsville continued to be the major town and the business center of the area.

Early Twentieth Century

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the railroad took a route through St. Paul, in the southern part of Madison County, rather than through Huntsville. St. Paul was a boom town and, at one point, outgrew Huntsville and petitioned to become the county seat. Huntsville was able to maintain its position by virtue of its history and more central geographic location.

The 1920s were a time of prosperity for Huntsville. A high school (the State Vocational School) was built, electricity became available, and automobiles began to be seen around town. Timber was still a profitable industry, and tomatoes and fruit were important cash crops. Bootlegging was also profitable, and Huntsville developed a reputation for wild living. The town was legally incorporated on July 16, 1925.

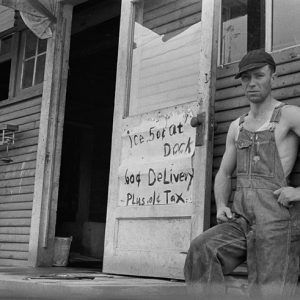

The Great Depression hit all of Madison County hard, though. The practices common in the timber industry had led to erosion, and the hilly soil was not suited to row crops such as corn or wheat. Even the small cash crops and subsistence crops that farmers had relied upon failed or became unprofitable. Madison County had cases of rabies, diphtheria, and malaria, as well as malnutrition. The population of the county declined, the railroads were dismantled, and the timber industry collapsed. Without the support of surrounding agriculture, Huntsville had no customers for its businesses.

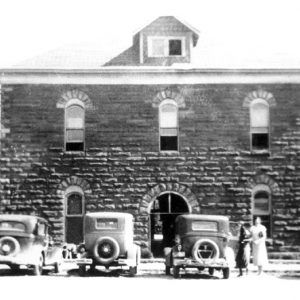

New Deal work projects built roads and electric lines. The current four-story courthouse was dedicated on November 30, 1939. In 1993, the Art Deco structure was added to the National Register of Historic Places. But there was essentially no industry to support the population.

World War II through the Faubus Era

World War II took able-bodied men from Huntsville and extended the hard times of the Depression. However, as demand for chickens to supplement military rations increased the need for poultry, this variety of farming began to offer hope for local agriculture. Northwest Arkansas entrepreneurs such as the Tyson and George families developed efficient methods and made forays into marketing, increasing consumer demand for poultry. Poultry and then cattle farming became the mainstays of the area’s economy.

The thirty-seventh governor of Arkansas, Orval E. Faubus, lived in Huntsville, where his famous 12,000-square-foot house was built in the late 1960s by renowned architect E. Fay Jones. It is east of town on Governor’s Hill. Faubus holds the distinction of continuously serving longer than any other Arkansas governor. He is buried in Madison County in the Combs Cemetery.

Modern Era

Huntsville continues to be largely agricultural. The main industry in town is the Butterball Turkey Plant. Labarge Electronics is another important employer. Construction is a significant source of employment, as a natural result of the high level of growth in the county. Otherwise, Huntsville continues to provide goods and services for the surrounding agricultural communities.

School consolidations established Huntsville as the center of education in Madison County. New roads have made Huntsville more accessible. Immigrants from Mexico have brought the beginnings of new ethnic diversity to Huntsville, yet Huntsville remains a classic Ozark town.

Science fiction author Suzette Haden Elgin made her home in Huntsville.

For additional information:

Embry, Callie S. “Communication Infrastructure Theory: A Rural Application.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2019.

Hatfield, Kevin. A Chronological History of Huntsville, Arkansas: In Celebration of the 175th Anniversary of the Founding of the City. Huntsville, AR: Madison County Genealogical and Historical Society, 2013.

History of Benton, Washington, Carroll, Madison, Crawford, Franklin, and Sebastian Counties, Arkansas. Chicago: The Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1889.

Sisk, Gloria J. Madison County: Remembrances of the Past. N.p.: 1986.

Whittemore, Carol. Fading Memories: A History of the Lives and Times of Madison County People. 3 vols. Huntsville, AR: Madison County Record, 1989, 1992, 2000.

Rebecca Haden

Fayetteville, Arkansas

Joy Russell

Witter, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.