calsfoundation@cals.org

Forrest City Riot of 1889

In the 1888 election, the Union Labor Party, which included farmers of the Agricultural Wheel, allied with the Republicans to challenge the Democrats. Aware of black Arkansans’ important electoral support of this movement, white Democrats responded by launching an effort to end African Americans’ political participation. In St. Francis County in eastern Arkansas, which had become a black-majority county by 1890, the Wheel/Republican alliance became politically powerful. In 1888, county Union Laborites and Republicans formed a fusion ticket to challenge the previously dominant Democrats. Much to the Democrats’ dismay, three black Republicans captured the offices of county assessor, treasurer, and coroner, and white Union Labor candidates won the offices of sheriff, county clerk, and county judge. Shortly after the election, St. Francis County Democrats warned of the inevitability of “negro domination” unless “some lawful means [was] used to prevent [blacks’] election.”

In May 1889, school elections in Forrest City (St. Francis County) turned violent. Five white Democrats and one black Republican, Americus M. Neely, made up the school board. Editor and manager of local Republican newspaper the Advocate, Neely was also a grocer, a Wheel member, and an outspoken county black leader. The Democratic board members supported the white principal of the Forrest City public schools, but Neely opposed him. Rising tensions involved more than the school board members’ differences over the principal. Four positions on the board were to be filled. Two of the white Democratic board members’ terms had expired. Neely was slated for a patronage appointment in Little Rock (Pulaski County) as receiver of federal lands. White Democratic board member Jesse W. Wynne was resigning because of relocation outside the county. Local whites feared that African Americans would win control of the board and thus control the affairs of the white, as well as the black, schools. Perhaps to defuse some of the hostility, Neely proposed a fusion ticket in which the Union Labor/Republicans and the Democrats would each nominate two board candidates, but the Republicans, led by black county coroner G. W. Ingram, rejected it. The board thus withheld Neely and Wynne’s resignations. The election would proceed, but voters would only be choosing between the two white Democratic members seeking reelection and their opponents. Before election day, the Democrats and the Union Labor/Republicans allegedly threatened violence to install their candidates in office. On the election day afternoon of May 18, the racial and political tensions exploded in what became known as the Forrest City Riot.

Near the polling place, an altercation occurred between Neely and board president James Fussell, one of the board members seeking reelection, in which the black leader was knocked down. Neely ran to John Parham, a former sheriff and Union Laborite, for protection. As city marshal Frank Folbre, a white Democrat, commanded the peace, deputy county clerk Tom Parham, John Parham’s son, came running and fired at the men, fatally wounding Folbre. As he fell, Folbre fired and killed Tom Parham. As he was running over to help, a stray bullet killed the Republican/Union Labor sheriff, D. M. Wilson, a former Democrat. John Parham and Neely were also wounded. Neely fled to his newspaper office, where he and his father, Henry, and younger brother, Ed, barricaded themselves. Following the violence, black county coroner and school board candidate G. W. Ingram quickly left town with orders never to return, and the Democratic school board incumbents were unanimously reelected.

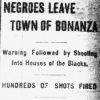

During the night, shots were reportedly fired into the Advocate building. On the morning of May 19, a bloody riot turned bloodier. Colonel Van B. Izard of the local militia, who had been newly commissioned as sheriff by Governor James P. Eagle, and a group of men went to Neely’s office. After Izard’s unsuccessful search of the building for Americus Neely, Henry and Ed Neely surrendered. Izard and several others led the two men to the jail with pistols drawn to keep the increasingly unruly crowd off of them. Izard’s remaining men stormed the building and found Americus Neely lying on the ground under the floorboards. As some of the men rushed to the front and back of the building, the rest fired a flood of bullets into Neely. His body was reportedly turned over to his relatives.

By 1891, Democrats had had enough of the political turmoil exemplified by events in St. Francis County. In the early 1890s, a new election law, the poll tax, and the white primary—combined perhaps with memories of political violence and the decimation of black leadership exemplified by the Forrest City Riot—secured black (and a significant amount of poor white) disfranchisement in Arkansas. In St. Francis County, by 1900, all white Democratic candidates for county offices ran unopposed.

For additional information:

Stockley, Grif. Ruled by Race: Black/White Relations in Arkansas from Slavery to the Present. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2008.

Welch, Melanie K. “Violence and the Decline of Black Politics in St. Francis County.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 60 (Winter 2001): 360–393.

Melanie K. Welch

Auburn, Alabama

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.