calsfoundation@cals.org

Flanigan Thornton (Lynching of)

On April 19, 1893, an African-American man named Flanigan (sometimes referred to as Flannagan or Flannigan) Thornton was hanged in Morrilton (Conway County) for allegedly murdering constable Charles Pate. While there are no records for Flanigan Thornton in Arkansas, he may have been the ten-year-old living with his parents Hyram and Chasity Thornton in Desoto County, Mississippi, in 1880 and working as a farm hand; this would have made him twenty-three at the time of the lynching. Charles Pate was born in White County, Arkansas, but by 1891, when he married Alice Phelps, he was living in Conway County.

According to newspaper accounts, the alleged murder happened on April 4 near Menifee (Conway County) station, about fifteen miles from Morrilton. According to the Decatur, Illinois, Daily Republican, Pate went to Thornton’s home and asked his wife about someone for whom he had a warrant. She told him where the suspect was, but he did not find him there and returned to Thornton’s house and abused Thornton’s wife. Thornton, hearing about this, went to find Pate and “abused him considerably.” Pate returned to Plumerville (Conway County) and swore out a warrant against Thornton. When he went back to arrest Thornton the next day, Thornton saw him coming and shot him twice. Thornton was arrested and jailed in Morrilton. According to historian Kenneth Barnes, Thornton admitted shooting Pate in the abdomen but asserted that Pate had fired first. Thornton’s attorney, William L. Moose, feared for Thornton’s safety and asked Sheriff Benjamin G. White to move him to a safer location. White laughed and refused.

According to the Republican, a grand jury indicted Thornton for second-degree murder at a special session of the circuit court held on April 18 and held him over to be tried the next day. Local residents were apparently disappointed that the indictment was not for first-degree murder, and early in the morning of April 19, a group of about twenty men forced their way into the sheriff’s office and demanded the keys to Thornton’s cell. They took Thornton to the nearby railroad tracks, where he was first hanged from a sign at C. T. Black’s store. The sign broke, however, and Thornton was shot and then dragged twenty feet away, where he was strung up again. His body was left hanging. The members of the mob were masked to conceal their identities, but the Republican noted that “there were a number of parties from the country in town.” A coroner’s jury was empaneled later that day, but proceedings were adjourned until Friday so missing witnesses could be found and interviewed. On April 20, 1893, the Russellville Democrat reported: “In view of the extenuating circumstances Thornton’s fate is most unfortunate and the law-abiding citizens of Morrilton deplore the tragedy.”

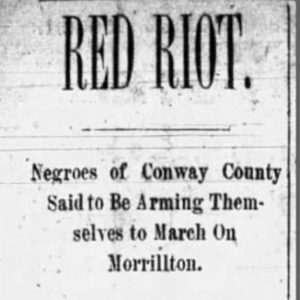

Rumors soon circulated that there had been a riot following the lynching. According to the April 21 edition of the newspaper, the Arkansas Gazette received a report around 2:45 that morning that “a serious riot occurred at Morrilton last night and that a mob of negroes took possession of the town. It is said that there was considerable fighting and that the Sheriff was killed and others wounded.” Armed whites were apparently patrolling the town. The Gazette had been unable to contact those in Morrilton and reported that it was possible that Sheriff White was only wounded by an accidental shot from one of those patrolling. They asserted, however, that African Americans in the area were threatening to wipe out the town of Morrilton. Although the Gazette declined to refute this account, on April 22, Oregon’s Daily Morning Astorian reported that everything was quiet at Morrilton, and “there was no trouble there, nor has there been any of lawless nature since the linching [sic] of Thornton.” The Port Gibson Reveille confirmed this on April 28, saying that reports of the riot were untrue, and that the sheriff and a group of armed citizens had merely gone to investigate a late-night commotion resulting from a crew unloading cross-ties from a train, at which the sheriff was accidentally wounded. According to the Reveille, “Nine-tenths of the ‘race wars’ published as occurring in the south have no better basis of fact than the one at Morrilton….Everyone ought to have learned by this time that the American negro is one of the most peaceable, inoffensive, and submissive members of the human family.”

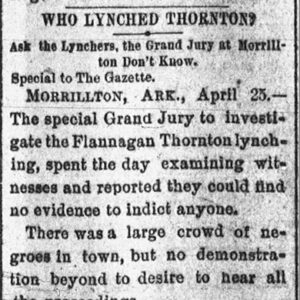

By April 20, one arrest had been made, a jailor who was accused of being an accessory to Thornton’s lynching. He at first denied that he knew members of the mob, but he later said that he recognized them but refused to identify them because they had threatened to kill him. Prosecuting attorney Jeff Davis had also been threatened to prevent him from investigating the lynching but was undeterred. A grand jury was called, and according to the Russellville Democrat, Judge Jeremiah Wallace issued a strong charge, asserting that Thornton was already in custody at the time of his death, and was “shackled and manacled. He was deprived of his liberty and every means of self defense.” Despite this charge, on April 26, the Gazette reported that the grand jury “had spent the day examining witnesses and reported that they could find no evidence to indict anyone.” Although a large number of African Americans had come to town for the proceedings, there was no trouble, and they seemed intent only on hearing the proceedings.

Governor William M. Fishback promised the full aid of the state in prosecuting members of the mob and, according to the Russellville Democrat, by May 4 was offering a reward of $300 for each mob member captured. According to the Democrat, “Not a single expression has come under our observation tending to justify or approve the crime, on the contrary, the condemnation has been so general and so pronounced as to leave no doubt as to the status of public sentiment in regard to the outrage.” Despite all efforts, however, the only person convicted in the case was the jailor, who was named an accessory.

For additional information:

Barnes, Kenneth C. Who Killed John Clayton? Political Violence and the Emergence of the New South, 1861–1893. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998.

“Happenings Round About.” Russellville Democrat, May 4, 1893, p. 3.

“Morrilton Was Orderly.” Daily Morning Astorian (Oregon), April 22, 1893, p. 1.

“Phantasmal Race Wars.” Port Gibson Reveille (Mississippi), April 28, 1893, p. 3.

“Red Riot: Negroes of Conway County Said to Be Arming Themselves to March on Morrilton.” Arkansas Gazette, April 21, 1893, p. 6.

“The Supremacy of the Law.” Russellville Democrat, May 4, 1893, p. 2.

“Thornton Mobbed.” Russellville Democrat, April 20, 1893, p. 3.

Untitled. Decatur Daily Republican (Illinois), April 20, 1893, p. 1.

“Who Lynched Thornton?” Arkansas Gazette, April 26, 1893, p. 1.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Flanigan Thornton Lynching Article

Flanigan Thornton Lynching Article  Flanigan Thornton Lynching Article

Flanigan Thornton Lynching Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.