calsfoundation@cals.org

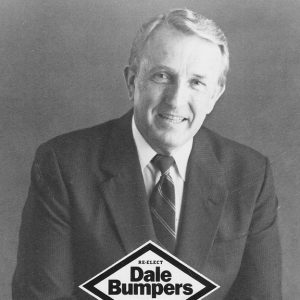

Dale Leon Bumpers (1925–2016)

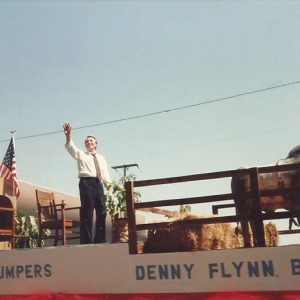

Thirty-eighth Governor (1971–1975)

Dale Leon Bumpers was one of the state’s most successful politicians in the last half of the twentieth century. As governor, Bumpers initiated the enactment of historic legislation, including a restructuring of the tax system and a reorganization (with Act 38 of 1971) of the state’s government, and as a U.S. senator (1975–1999), he was a fiscally conservative, socially liberal legislator recognized for his oratorical skills.

Dale Bumpers was born on August 12, 1925, in Charleston (Franklin County). He was one of four children born to William Rufus and Lattie (Jones) Bumpers. His father worked for the Charleston Hardware and Funeral Home beginning in 1924. In 1937, he and a partner bought the business.

Bumpers spent his childhood in Charleston in the lean years of the Depression. He held many part-time jobs, including picking cotton and peas, picking up plowed potatoes, working at a cannery, delivering newspapers, driving the family’s funeral vehicle, and working as a butcher at a grocery store. His father served one term in the state House of Representatives and encouraged his sons to attend all political events in the vicinity of Charleston. He taught them there was “nothing as exhilarating as a political victory and nothing as rewarding or as honorable as being a dedicated, honest politician who actually makes things better and more just.”

After graduating from Charleston High School in 1943, Bumpers briefly attended the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) and joined the U.S. Marines later that year. When World War II ended, he was on a ship heading to the Pacific theater. After he was discharged in July 1946, he returned to UA and graduated two years later with a BA in political science. He received a law degree in 1951 from Northwestern University at Evanston, Illinois.

In 1949, while he was at Northwestern, Bumpers’s life was dramatically altered in two ways. In March, his parents died as a result of a car crash. Then, on September 4, he married a former Charleston classmate and longtime girlfriend, Betty Lou Flanagan.

After Bumpers graduated from law school, he and his wife returned to Charleston. There, they had and raised three children. He took over the operation of his father’s store, now the Charleston Hardware and Furniture Company, which he owned until 1966, when he sold it and began operating a 350-acre Angus cattle ranch. He was admitted to the Arkansas Bar in 1952. In his years of practicing law (1952–1970), he lost only three cases. As the title of his memoir indicated, he was, indeed, “the best lawyer in a one-lawyer town.”

Early in his legal career, the Charleston School Board asked his advice on how it should respond to the U.S. Supreme Court decision in the 1954 case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, which found the segregation of public schools on the basis of race to be unconstitutional. Bumpers advised the school board to comply with the decision immediately. In July 1954, the board voted to desegregate it schools, and on August 23, 1954, the school year began with eleven African American children attending schools in Charleston. This prompt action to desegregate public schools was rare—the Charleston School District was the first in the eleven states that comprised the former Confederacy to integrate their public schools following the Supreme Court decision.

Despite his prominence as a Franklin County lawyer and businessman, Bumpers’s first attempt at elected office ended in failure. In 1962, he ran for the House seat that his father once held. Although he won more than ninety percent of the vote in Charleston, he lost the election.

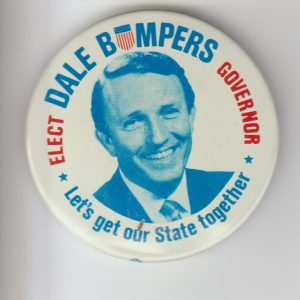

The loss did not deter Bumpers from seeking office again. He considered running for governor in 1968 but decided to wait. When he ran in 1970, he faced seven candidates in the Democratic primary. The front-runners were former Governor Orval Faubus, who had served six terms from 1954 to 1966, Attorney General Joe Edward Purcell, and Speaker of the House Hayes McClerkin. An early poll showed Bumpers with about one percent of the vote.

Bumpers overcame his early lack of name recognition and support. His charismatic personality was showcased through strong television ads, and his personality and progressive positions attracted enthusiastic support, especially in western Arkansas. He finished second in the primary with twenty percent of the vote; Faubus received thirty-six percent. Bumpers easily defeated Faubus in the runoff and received sixty-two percent of the vote in the general election, defeating the Republican governor, multimillionaire Winthrop Rockefeller, who was seeking a third term. Bumpers won reelection in 1972.

As governor, Bumpers had significant successes. He gained legislative approval of several major reforms that Rockefeller had championed but had been unable to convince the Democrat-controlled state legislature to enact. For example, in his first term, Bumpers proposed a plan, similar to one that had been advocated by the Rockefeller administration, to reorganize state government to reduce drastically the number of agencies reporting to the governor. Also, he proposed to raise income taxes to provide funds to increase teachers’ salaries. This proposal to increase income taxes and make the tax rates more progressive required, under the state constitution, the votes of three-fourths of the members of both houses of the state legislature. He successfully guided both controversial reforms through the legislature.

His other reforms—some borrowed from Rockefeller and others not—were numerous. In his first term, he sponsored a home rule law that gave more powers to cities, the creation of a consumer protection division in the attorney general’s office, repeal of the “fair trade” liquor law, expansion of the state park system, a prison construction program, and improvements in social services for elderly, disabled, and developmentally challenged citizens. During Bumpers’s second term, his legislation included creation of a state-supported kindergarten program, free textbooks for high school students, a major construction program at the state’s colleges, elimination of the prison trusty system, and the encouragement of a community college system through increased state payments of the operational costs of these institutions.

During Bumpers’s administration, according to Arkansas Gazette political reporter Doug Smith, “there was more substantial progressive legislation enacted than in any other four-year period in Arkansas history, probably, and while that was going on, Bumpers was casually establishing himself as one of the more skillful politicians the state ever produced.” Walter DeVries and Jack Bass, in their analysis of the “transformation of Southern politics,” said that, as governor, Bumpers personified “the emerging politics of progressive moderation in the South.”

Although Bumpers’ governorship was widely viewed as a success, he did not enjoy the position. He wrote in his autobiography that he “intensely disliked most of my time as governor…. I spent more time trying to make sure bad things didn’t happen than I spent trying to make good things happen.” Perhaps this view of his job contributed to his caution in making decisions. Smith of the Arkansas Gazette wrote that, in the midst of controversy, Bumpers could be “maddeningly noncommittal in his public utterances.” Christopher Lyon, a reporter for the New York Times, described Bumpers as a “caricature of blandness” who was known for “tortured temporizing over big decisions.” DeVries and Bass accused Bumpers of not providing “bold leadership that helps shape public opinion.”

In 1974, as he was completing his fourth year as governor, Bumpers challenged the incumbent U.S. senator, J. William Fulbright, in the Democratic senatorial primary. Fulbright, who was finishing his thirtieth year as senator, had been in the public eye since he was a star football player for UA. He had served as UA president and was an internationally known intellectual who, as chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, had been a leading opponent of the Vietnam War. The decision to run against Fulbright was a difficult one. Bumpers had long been an admirer and supporter of Fulbright; he considered him a friend and great senator. Nevertheless, he had polls showing not only that he could easily defeat Fulbright, but that Fulbright was vulnerable to other possible opponents. Bumpers wrote of his decision, “I didn’t want to oppose him; on the other hand, I would never forgive myself if he was defeated by someone whose views were an anathema to me.”

Bumpers defeated Fulbright decisively, receiving sixty-five percent of the vote. He also won the general election by a wide margin and took his seat as a senator in 1975. With his electoral victories over Faubus, Rockefeller, and Fulbright, Bumpers was nicknamed “the giant killer” by the New York Times.

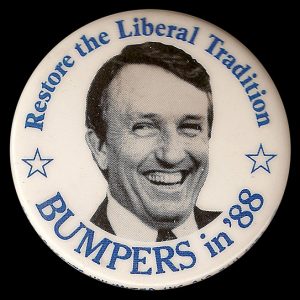

In Bumpers’s twenty-four-year career in the Senate, he was chairman and senior minority member of the Committee on Small Business and served on the Senate Appropriations Committee and the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. He considered running for president in 1976, 1984, and 1988, but each time he decided against it. He explained his decision in his final speech to the Senate: “By the time I felt I was qualified to be President, I decided that it demanded a price that I was not willing to pay.” He explained that he was deterred by the extreme partisanship in presidential politics, the need to raise massive amounts of money, and the negative impact of a race on his family.

As senator, Bumpers consistently supported environmental legislation and efforts to expand and fund the National Park System. For example, he won approval from Congress to designate 91,000 acres in Arkansas as wilderness areas. As a result of his efforts to preserve parklands and wilderness areas, the Wilderness Society awarded him the Ansel Adams Award in 1998.

A fiscal conservative, Bumpers was an early supporter of efforts to reduce the national debt and was often a critic of military spending. He opposed expenditures on such projects as the space station and the Strategic Defense Initiative—better known as “Star Wars”—and led the successful fight to stop construction of a superconducting supercollider. He also tried to reform mining and other laws regulating the use of natural resources on public lands to prevent private companies from taking resources without paying fair royalties to the U.S. treasury.

Bumpers consistently opposed efforts to amend the U.S. Constitution. He voted against thirty proposed amendments, including one to allow prayer in public schools.

Bumpers described his vote on the Panama Canal treaties as the most politically difficult for him. He voted for the treaties, which returned ownership of the canal to Panama, in the late 1970s. His vote was politically unpopular in Arkansas and cost him support in future elections.

After Bumpers left the Senate on January 3, 1999, President Bill Clinton asked him to return to the Senate floor to make the closing argument on his behalf at Clinton’s impeachment trial. The House had approved two articles of impeachment against Clinton, and as provided by the Constitution, the Senate’s responsibility was to conduct a trial and vote either to convict the president and remove him from office or to dismiss the charges. On January 21, 1999, Bumpers addressed the Senate trial to make the final summation of why the Senate should dismiss the impeachment charges against Clinton. His speech was widely praised; Mary Lefkowitz of the New York Times credited Bumpers with persuading many Americans that President Clinton should not be removed from office. Two weeks after his speech, the Senate acquitted Clinton of the impeachment charges, allowing Clinton to remain in office.

After leaving the Senate, Bumpers became director of a Washington DC think tank, the Center for Defense Information, which is concerned with defense and defense expenditure issues. In 2000, he joined the law firm Arent Fox Kintner Plotkin & Kahn in Washington DC. He retired at the end of 2008 and moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County).

Bumpers died at his home in Little Rock on January 1, 2016.

For additional information:

Bowden, Bill. “Ex-Governor, Senator Bumpers Dead at 90.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 3, 2016, pp. 1A, 8A–9A.

Bumpers, Dale. The Best Lawyer in a One-Lawyer Town: A Memoir. New York: Random House, 2003.

———. “Interview with Dale Bumpers about Integration of Charleston High School.” September 4, 2002. Video at Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Bobby L. Roberts Library of Arkansas History & Art, Central Arkansas Library System: Dale Bumpers Video Interview (accessed July 6, 2023).

———. “Interview with Dale Bumpers: Arkansas Governor’s Mansion Project.” April 10, 2008. Audio at Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Bobby L. Roberts Library of Arkansas History & Art, Central Arkansas Library System: Dale Bumpers Audio Interview (accessed July 6, 2023).

Dale Bumpers Papers, 1970–1974. Center for Arkansas History and Culture. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Dale Bumpers Papers, 1974–1998. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Donovan, Tom P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Dumas, Ernest. “The Life and Times of Dale Bumpers.” Arkansas Times, January 14, 2016, pp. 14–18, 20–23. Online at http://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/the-life-and-times-of-dale-bumpers/Content?oid=4238665 (accessed July 6, 2023).

Lancaster, Bob. “The Great One.” Arkansas Times, August 28, 1998, pp. 10–13.

Sanders, Donald Randy. “The New South Gubernatorial Campaigns of 1970 and the Changing Politics of Race.” PhD diss., Louisiana State University, 1998. Online at https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6760/ (accessed July 6, 2023).

Smith, Doug. “Dale Bumpers: He’ll Be Remembered as Right, Not President.” Arkansas Times, January 8, 1999, pp. 9–11.

Whitley, Amanda Louise. “Women during the Governorship of Dale Bumpers.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2012.

Dan Durning

University of Georgia, Athens

This entry, originally published in The Governors of Arkansas, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. The Governors of Arkansas is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Dale Bumpers was a great leader, as was the late Paul Simon. I was Paul’s student coordinator. I brought the Reagan Democrats to Paul Simon in 1984. Thanks, Dale Bumpers, for the memories and thanks to Dale Bumpers, Paul Simon, and Kenneth J. Gray for helping work with Republicans and Democrats. You three men are now in Heaven.

As Arkansas governor, Bumpers successfully led the effort championed by his wife, Betty, to achieve a 90% level of childhood immunizations in Arkansas. The motto was “every child by ’74.” He also sponsored successful federal legislation to establish the federal immunization initiative during the Carter administration; the program was repealed in 1980 by then-president Jimmy Carter. While forty-nine states assigned immunization investigator duties to their state venereal disease investigators, Betty Bumpers made sure her home state had four federal immunization field representatives for the entire state, plus two state people (stationed at the State Health Department in Little Rock). The health department in Little Rock also served as the Central Region.

The four federal immunization field representatives were stationed at the other four State Regional Health Offices as follows: Northwest Region, but stationed at the Boone County Health Unit–Karen Shepherd

Northeast Region, stationed at the Northeast Regional Health Office in Jonesboro–Cecilia Bigham.

Southeast Region, stationed at the Southeast Regional Health Office on the campus of the University of Arkansas at Monticello–Betty Elliott.

Southwest Region, stationed at the Southwest Regional Health Office at Nashville–Randy O. Bowling.

The state Medical Director of Immunization was Gordon Page Oates, MD. The year 1980 was the last year of the IFRs and the Betty Bumpers federal immunization program.