calsfoundation@cals.org

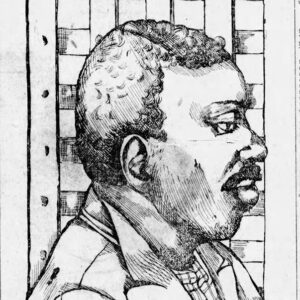

Charles Young (Lynching of)

Charles Young, an African American man, was burned alive by a mob near Forrest City (St. Francis County) on October 20, 1902, accused of raping and killing a white woman.

Ed Lewis, “a respected farmer,” was working at a fishing camp on the St. Francis River when his wife left their home on horseback about seven miles from Forrest City on October 13, 1902, to visit him. While on the way, according to newspaper accounts, someone attacked her, and she was “carried some thirty yards into the thicket…along the side of the road and there ravished and murdered.” When her riderless horse arrived at the camp, Lewis sent a messenger to go toward his house and investigate. When her horse suddenly recoiled at one point, the messenger found Mrs. Lewis “terribly wounded, her skull crushed in at the back part of her head, a deep cut on the forehead and other wounds.” She was taken home and died that night.

The next day, the county coroner investigated, initially thinking she may have been thrown from her horse and fatally injured. Visiting the place where she was found, however, he discovered that “part of her hair had been torn out and there were finger marks on her throat, and the surroundings showed there had been a desperate struggle.” He concluded that her “death [was] at the hands of an unknown party.” A Forrest City newspaper added that “suspicion has fallen upon a certain negro, whose name is withheld, and he is being watched,” while another paper predicted that “summary vengeance will be the result if the perpetrator is found.”

The suspect was Charles Young, and he fled to Linden Island on the St. Francis River to hide from a posse that was searching for him. He was recognized while crossing the river on a ferry, and ferryman Nathan Williams pulled a shotgun on him as he “made a dash for liberty as the boat touched the bank.” Young hid in a ravine, but as members of the posse began crossing the river, he “made a desperate effort to escape” before being downed by a shotgun blast from Williams. A pair of Forrest City officers arrived and “succeeded…in evading the pursuing posse and landed the criminal safely in jail” on October 19.

Fearing mob violence, Sheriff W. E. Williams called circuit judge H. N. Hutton, who agreed to come to Forrest City “and hold an immediate trial.” When informed of this, the leaders of the posse agreed to “let the law take its course.”

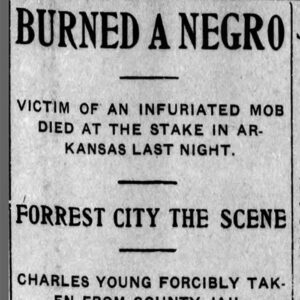

On the night of October 20, 1902, though, “hotheads in the crowd” led a mob to the jail and demanded that the deputy on duty give them the keys to the cells. When he refused, they attacked him, seized the keys, “and breaking into the jail door with sledge hammers, dragged the prisoner out.” They initially planned to tie him to a nearby telephone pole and burn him alive, but City Marshal W. W. Rainbolt convinced them to lynch him outside of Forrest City.

Young was dragged about a half mile outside of town before being chained to a tree near a stave mill while “all sorts of inflammable material was heaped around him.” The doomed man told the crowd that another man, Henry Armstrong, was the real killer; Armstrong was subsequently found to have been “at work on a bridge with one of Forrest City’s best citizens” when Mrs. Lewis was attacked.

“An immense throng of people” watched as the pyre was lighted; “the negro begged piteously for life, but the mob turned deaf ears.” The Arkansas Democrat reported that “the shrieks and agonizing groans of the negro were terrifying in the extreme as the flames leapt about him,” and that the dying man cried out, “I did it. For God’s sake turn me loose,” though “he was so near gone at this time…it is doubtful if he knew what he was saying.”

Later reports supported the accusation of Young being the guilty party, with newspapers reporting that “the wife of Young says he came home about the time of the murder, excited and with his clothes bloody. Young’s protestations of innocence and his declaration that Henry Armstrong committed the murder have been effectually set at rest.”

Young’s lynching was “much to the regret of a greater number of conservative people, who did not think the proof of the crime conclusive enough to justify such hasty action,” and the Democrat editorialized that “we had hoped that the people of this state would never stoop to such barbarous practices. It is bad enough when prisoners are taken from the authorities and lynched. It is so much worse when we resort to the methods of the uncivilized barbarians.”

No one appears to have been prosecuted for participating in the lynching of Charles Young.

For additional information:

“Burned a Negro.” Fort Smith Times, October 21, 1902, p. 1.

“Charles Young Burned by a Mob at Forrest City.” Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, October 21, 1902, p. 1.

“Chas. Young, Negro Murderer, Burned at Forrest City.” Arkansas Democrat, October 21, 1902, p. 3.

“FearfulAct [sic] Is Expiated.” Helena Weekly World, October 22, 1902, p. 2.

“A Horrible Crime.” Forrest City Times, October 17, 1902, p. 2.

“Murderer Unknown.” Newport Daily Independent, October 16, 1902, p. 1.

“Negro Burned in Arkansas.” Arkansas Democrat, October 21, 1902, p. 4.

“Proof of His Guilt.” Fort Smith Times, October 22, 1902, p. 4.

“State News.” Arkansas Democrat, October 16, 1902, p. 6.

“Woman Brutally Murdered.” Southern Standard, October 23, 1902, p. 1.

Mark K. Christ

Central Arkansas Library System

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Charles Young

Charles Young  Charles Young Lynching Story

Charles Young Lynching Story

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.