calsfoundation@cals.org

buZ blurr (1943–2024)

aka: Butler, Russell

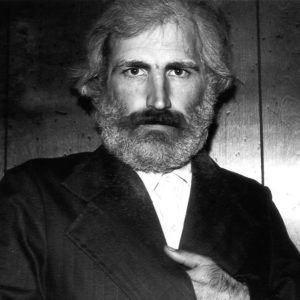

Russell Butler (a.k.a. buZ blurr) was a visual and conceptual artist whose dedication to his post-postmodern artistic vision placed him at the forefront of the contemporary mail-art, stamp-art, and conceptual art movements. Although internationally known, he remained rooted in the traditions of Clark County, where he resided until his death.

Russell Butler was born on August 23, 1943, in Lafe (Greene County). His father, Eugene H. Butler, was a track foreman on the Missouri Pacific Railroad, and his mother, Cleda Elmira Mullins Butler, was a restaurant manager in Forrest City (St. Francis County). Butler had one sister. The family moved often to follow his father’s railroad career in track maintenance. After attending seven different schools around Arkansas, Texas, and Louisiana, Butler graduated from Gurdon High School in Gurdon (Clark County) in 1961.

Butler attended Henderson State Teachers College (now Henderson State University) in Arkadelphia (Clark County) from the fall of 1961 through October 1964, studying drawing, painting, printmaking, and ceramics; he earned enough hours for a major in art and a minor in psychology but lacked the requisite foreign language and biology courses for a BA degree. While attending Henderson, he was hired by the Missouri Pacific Railroad to replace vacationing trainmen in Gurdon. In 1964, he began working for the railroad permanently.

On Christmas Eve 1964, Butler married his high school sweetheart, Emmy S. Blanton; together, they had three children. While employed by the railroad, Butler continued his studies in art, writing, and photography, especially vernacular everyman photography, such as Polaroids and photo booths.

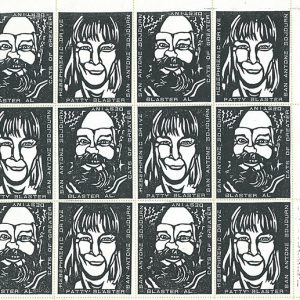

In 1972, he discovered the international phenomenon of mail art, which entailed sending small, often multi-media, works through the mail. Through the counterculture communications alternative of mail art, visual artists and poets could challenge social conditions and exchange their work with like-minded artists. This civilization-unifying method of exchange has been interpreted by scholars as a precursor to the Internet. Eschewing digital formats, Butler continued this outlet of expression by focusing on a sub-genre to mail art, called artist’s stamps—or artistamps—as an exchange platform with other artists.

Every six years, Butler documented (in text and pictures) international mail-art conferences, including InterDada 80 in San Francisco and Ukiah, California (May 1980); Decentralized Networker Congresses in Dallas and New York (1992); and Move Your Archive (2016).

Controversy sometimes surrounded his oeuvre. For instance, Butler was accused of being the worst “Quik Kopy Crap Artist” of the neophytes who joined the mail-art network after the publication of two Rolling Stone articles about correspondence art by Fluxus artist Ken Friedman in 1972. Many believe, however, that controversy only enhanced the reputation of Butler as an artist.

Butler published one-of-a-kind bookwork assemblages called hoohoohobo/fortuitouslogos, such as Month of Sundays, a book of color SX-70 Polaroids consisting of photographs taken on thirty consecutive Sundays (July 10, 1977, through January 29, 1978), and “The Caustic Jelly Posts,” a self-produced illustrated essay consisting of a box of five sets of one to fourteen folders (1981–1997).

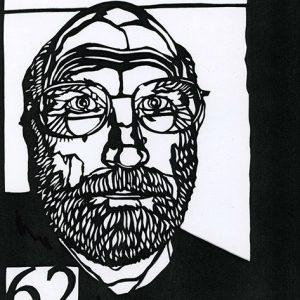

Butler’s work was featured in numerous publications, archives, and exhibitions, including an installation of a 3′ x 21′ painting as part of the 2001 group exhibit Widely Unknown at Deitch Projects in New York, which was a tribute to San Francisco colleague Margaret Kilgallen. After he retired from the railroad in August 2003, Butler purchased a vanity one-man exhibit of thirty-five framed pieces of his stencil portraits at the International Curatorial Space in Manhattan.

In the May 2013 issue of Fluke FanZine, the chief curator at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Canada, described Butler as “a great correspondent…[who] has made his ‘caustic jelly post’ artistamp portraits of more network artists than I have met or know. His work is striking in that while working from photos, they are more about the person than the photos on which they are based.” The August 2013 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine devoted a ten-page illustrated article to buZ blurr’s oeuvre. Hurray for the Riff Raff’s Alynda Segarra referenced him in their song “Colossus of Roads,” released in early 2024.

He died on January 26, 2024, at his home in Gurdon.

In spring 2024, the STRAAT Museum in Amsterdam hosted an exhibition prominently featuring buZ blurr—Moniker: An Origin Story: Unveiling the Hidden Legacy of Hobo Monikers’ Impact on Global Street Art and Graffiti Culture—with family members attending the March 2024 opening.

For additional information:

Clancy, Sean. “Boxcar Artist from Gurdon Featured in Bookstore Show.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 11, 2019, p. 4E. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2019/apr/11/boxcar-artist-from-gurdon-featured-in-b/ (accessed February 5, 2024)

———. “His Whims Carried Far by Boxcars.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, February 4, 2024, p. 1B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2024/feb/04/his-whims-carried-far-by-boxcars/ (accessed February 5, 2024).

———. “Railroad Artist Has Fan’s Back.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 7, 2024, p. 1B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2024/apr/07/paper-trails-arkansas-railroad-graffiti-artist/ (accessed April 8, 2024).

Falco, Tav. “Rust Never Rests: buZ blurr’s Art Is an Exercise in ‘Time Stoppage.’” Arkansas Times. https://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/rust-never-rests-buz-blurrs-art-is-an-exercise-in-time-stoppage/Content?oid=29054796 (accessed October 20, 2020).

John Held Jr. Papers Relating to Mail Art, 1973–2013. Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC.

“Profile: buZ blurr.” Wooster Collective. http://www.woostercollective.com/post/profile-buz-blurr (accessed January 26, 2024).

White, Matt, and Matthew Thompson. “Wait of the World.” Oxford American, March 28, 2019. https://oxfordamerican.org/web-only/wait-of-world (accessed January 26, 2024).

Tav Falco

Hot Springs, Arkansas

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Artistamps

Artistamps  buZ blurr

buZ blurr  Stamp Art

Stamp Art

buZ was much admired by Alynda Segarra of the band Hurray for the Riff Raff. The new album (2024) has a song on it (“Colossus of Roads”) that pays tribute to him in these lyrics:

“Colossus of roads, buZ blurr in the night.

Cowboy hat and a cigarette,

Grease marker in my leather vest.

Let’s go paint the oil cans,

Write our names on a grain of sand.

No one will remember us,

Like I will remember us.”

I don’t know if they were friends or not.

Sorry to see this news. He and I exchanged many times over the years, and I even sent “keys” to help fill the Ford. See you on the other side someday, amigo.