calsfoundation@cals.org

Boxley (Newton County)

Located in the Buffalo River valley in the Boston Mountains of northern Arkansas, the unincorporated community of Boxley has a long and colorful past. A key strategic area during the Civil War, Boxley is now associated with conservation efforts of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Northern Arkansas was claimed by the Osage when the United States first acquired the land from France as part of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Although they lived in scattered communities in southern Missouri, the Osage frequented Arkansas for hunting and fishing. After a treaty removed the land from Osage control, the United States granted what would become Newton County as part of a Cherokee settlement. That treaty lasted approximately ten years, from 1818 to 1828, before the Cherokee were removed to Indian Territory, now the state of Oklahoma. Local tradition states that Henry Martain, a French settler, was associated with the Cherokee, as was his son-in-law, Jack Evans; historical proof is lacking for this tradition. Eventually, other settlers claimed land in the area, including Andrew Whitley, Samuel Whitley, Jesse Casey, and Adderson Villenes, with their families.

Walnut Grove Baptist Church was established in the area around 1840. Isaac Whitley was the first preacher of the congregation. A water-powered grist mill was built around the same time. A post office was established at the settlement in 1851; it was originally named Whiteleys, presumably after the Whitley family, although Jesse Casey was the first postmaster. During the Civil War, the settlement became one of the more important targets of Federal and Confederate attention because of the chemical nitre (used in munitions) that was mined from bat guano in a cave on the side of Cave Mountain, south of the settlement. Federal forces attacked and destroyed Confederate mining operations in the area in January 1863. More than a year later, on April 5, 1864, a skirmish was fought in the same area as Federal soldiers of the Second Arkansas Cavalry attacked and dispersed a band of roughly 250 Confederate guerrilla forces.

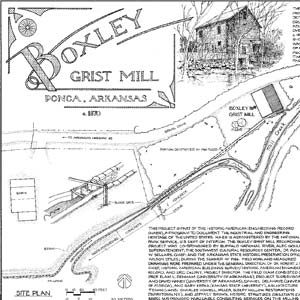

The community survived the war and began to prosper. The earlier mill was considered too small to meet the needs of the settlers and was replaced by a new structure, which in 1974 was added to the National Register of Historic Places. Although the Whiteleys post office was closed in 1866, it was reestablished in 1883 with the name Boxley. The new name was that of a recently arrived merchant who is remembered only as D. Boxley; however, the first postmaster of the new post office was Samuel Edgmon. In addition to the usual grain, cotton, chickens, and livestock, the Boxley area also produced turkeys, honey, and maple sugar. In 1882, the Carthage and Arkansas Mining Company established a lead smelter at Boxley. Though it contributed much to the planning of the community, the company found the cost of transporting the lead excessive and abandoned the operation.

A logging operation was established at Boxley early in the twentieth century. Hardwood trees were felled, with the wood transported down the Buffalo River to processing plants. Two small sawmills were constructed in Boxley, as well as a stave mill and a furniture factory. By 1930, most of the hardwoods, as well as the maple trees, had been harvested, and the lumber business closed down. Like the rest of the country, Boxley struggled through the Depression, although a cannery provided some jobs in the community during the 1930s. The post office was closed again in 1955.

In the middle of the twentieth century, Boxley gained national attention as some area residents wanted to have the Buffalo River dammed to provide hydroelectricity and recreational lakes, while others wanted to preserve the environment of the river. Local environmentalists and national politicians debated the issue for many years. Two state parks were established along the river: Buffalo River State Park in 1938 and Lost Valley State Park in 1966. In the end, the preservation of the river was assured when President Richard Nixon signed legislation creating the Buffalo National River, protecting nearly 100,000 acres along a 135-mile stretch of the river. Private ownership of land within the protected area is permitted, but restrictive scenic easements limit activities of the owners of that land.

During the 1970s, a counter-cultural community of men and women was established on 500 acres of land near Boxley. Calling their community Sassafras, the group went through several stages of development, becoming a women-only community and later inviting a multi-cultural community to develop. Later known as Arco Iris, the community eventually became a cooperative effort of men, women, and children, occupying 370 acres of wooded land.

Elk, which had once been native to Arkansas but had been hunted to extinction locally by the 1840s, were reintroduced to the Boxley area in 1981 in a cooperative program run by the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, the National Park Service, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, and local landowners. Licensed hunting of elk began in 1998. Boxley is on the Ozark Highlands Scenic Byway, a thirty-five-mile section of Highway 21that passes through the Ozark National Forest starting near Clarksville (Johnson County) and ending at the Buffalo River.

For additional information:

Johnson, James J. “Bullets for Johnny Reb: Confederate Nitre and Mining Bureau in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 49 (Summer 1990): 124–167.

Kennedy, Steele T. “An Enchanting Valley Comes Into Focus.” Arkansas Democrat Magazine, February 5, 1961, pp. 8–9.

Lackey, Walter F. History of Newton County Arkansas. N.p.: 1950.

Schnedler, Marcia. “All’s Quiet in Boxley Valley.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, March 15, 1998, p. 2H.

Steven Teske

Butler Center for Arkansas Studies

Boxley Mill

Boxley Mill  Boxley Bridge

Boxley Bridge  Boxley Community Building

Boxley Community Building  Boxley Elk

Boxley Elk  Boxley Grist Mill

Boxley Grist Mill  Grist Mill Plans

Grist Mill Plans  Newton County Map

Newton County Map  Walnut Grove Church

Walnut Grove Church

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.