calsfoundation@cals.org

Blytheville Boycotts of 1970–1971

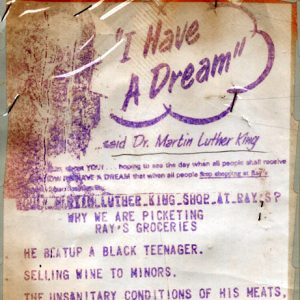

In the opening months of 1970, a group of African Americans in their mid-twenties sought to bring the social and cultural changes they had seen evolving in other parts of the world to Blytheville (Mississippi County). A graduate of Harrison High School (Blytheville’s black school), Bob Broadwater helped this group establish a chapter of the Black United Youth (BUY). The first public effort of this fledgling civil rights organization occurred soon after a local white grocer, Ernest Ray, beat a nine-year-old black boy with a crowbar for allegedly shoplifting. Ray’s grocery store was a fixture in the Elm Street commercial district. His store had a reputation for selling out-of-date meats and vegetables well past their prime.

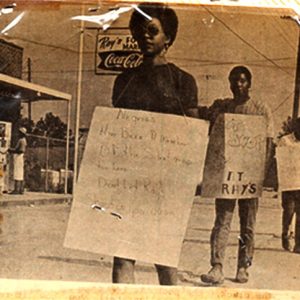

During a meeting in the home of Carter Roane (Sonny) Williams, the group decided to boycott Ray’s store with the goal of either forcing it to close or change its business practices. The boycott started the morning of Saturday, August 1, 1970, first with two marchers, Broadwater and his childhood friend Archie Cooper. Within an hour or two, the number of marchers had grown to twenty, and in just a few days the boycott had reduced Ray’s clientele to near zero. Despite black community support for the protesters, some African Americans continued to patronize the store throughout the boycott. Several older members of the community had directed that their retirement and social security checks be delivered directly to the store; they simply had no other means to shop elsewhere.

Throughout the twenty-eight-day boycott, Ray threatened to shoot Cooper, who was coordinating the marchers. Finally, on Friday, August 28, 1970, Ray and his nephew forced the issue by threatening Cooper with a twelve-gauge shotgun. As Cooper followed their directions to remove signs and other paraphernalia related to the boycott, Williams approached and was pressed into helping Cooper. Nervous about having the shotgun so close, Williams pushed the barrel away. While he was moving it, the gun discharged, fatally shooting him in the abdomen.

Ray and his nephew were arrested and charged with first-degree murder. Although the black community had been assured the charge was not bondable, the judge permitted Ray and his nephew to post a $25,000 bond and leave town for medical treatment. The black community retaliated with two nights of arson and vandalism targeting other white-owned stores that discriminated against blacks. On April 7, 1971, an all-white jury found Ray guilty of the lesser crime of voluntary manslaughter and sentenced him to two years in prison. The day after the conviction, Ray posted a $5,000 appeal bond and moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County). He died of natural causes on June 14, 1975. There is no record of his incarceration.

The boycott and the attendant shooting ultimately resulted in several benefits to the community. Opportunities for black employment increased substantially. Retail businesses began to treat the black community on a more equal basis. Community leaders began to address long-running infrastructure needs within black neighborhoods. Finally, in recognition of the importance of Williams’s death to the local civil rights activities, the city renamed the decade-old Southside Park as Williams Park.

Williams’s funeral on Monday, August 31, 1970, coincided with the culmination of years of planning by the district to integrate the high school and junior high schools. Black teachers had been teaching in the white Blytheville High School for years, and some black students had attended there as part of a Freedom of Choice integration plan implemented in 1964. Over the summer, Harrison High, the former black high school, had been converted to the Harrison Learning Center, where newly established special education and adult education programs would be held.

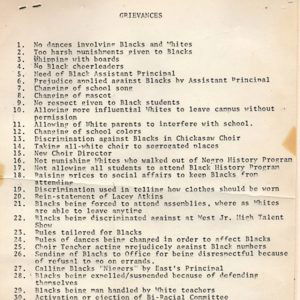

Although the school year appeared to proceed calmly, black students experienced both overt and covert discrimination from white students, faculty, and staff. About a week after Ray’s conviction, a group of students delivered a list of thirty-five grievances to the school administration for their consideration. Thursday, April 15, 1971, began with the arrest of thirty-eight students and four adults—including Broadwater and two students from Arkansas AM&N College (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff). One other adult—Joyce Cooper, the secretary of the Blytheville BUY chapter—avoided arrest by jumping out of the police van and running home. The students were gathering outside of the Harrison Learning Center to march to the high school and deliver their grievances.

Hearing of the arrests, other black students and their parents begin gathering at the front door of the high school to seek answers from the administration, preventing other students from entering the building. In order to calm the situation, the administration invited three well-known black ministers—the Reverends P. J. James, O. W. Weaver, and Emmanuel Lofton, who also taught at the high school—to address the crowd. Learning from the crowd of the morning’s arrests, Lofton arranged with the local police who had surrounded the group to escort the crowd to Williams Park.

The next three days saw a drop in attendance of some 400 students at the district’s high school and its two junior high schools. Eventually, the school board met with leaders of the student organization that led the boycott, supported by the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), to hear their complaints. The most important outcome of the meeting was a promise to investigate and discipline teachers and staff who demonstrated racist attitudes toward blacks and resolve other grievances. Also, the superintendent guaranteed physical safety for black students and agreed to set aside administrative discipline if they returned to school promptly.

The next day, about 300 white students staged a rally and protest in a bowling alley parking lot across the street from the high school. They protested the actions of the school board toward the black protesters and sought to prevent rumored changes to long-held school traditions. While a number of these protesters returned to school later in the day, two days later, on April 24, Superintendent Harris was forced to issue a public statement warning those who continued to boycott classes that they would be suspended for the remaining eleven days of school if they did not return to class. He also warned that continued absence would force the district to deny them credit for the semester.

Taken together, these two events represent a vital shift in Blytheville society as the white community began to recognize and react to the African-American community’s voice.

For additional information:

“29 Arrested in Wake of City’s Violence.” Blytheville Courier News, September 1, 1970, p. 1.

“$5,000 Bond Posted in Slaying of Picket.” Commercial Appeal, April 9, 1971.

“At BHS Some Whites Walk, Some Return.” Blytheville Courier News, April 22, 1971, pp. 1, 2.

“Board, NAACP to Meet.” Blytheville Courier News, April 20, 1971, pp. 1, 8.

“BHS Students Warned about Disruptions.” Blytheville Courier News, April 24, 1971, p. 1.

“City’s Schools Talk Topic.” Blytheville Courier News, August 21, 1970, pp. 1, 4.

“Expected Enrollment Down.” Blytheville Courier News, September 1, 1970, p. 1.

Kirk, John A. Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940–1970. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2002.

Laseter, Webb, III. “Ray Gets 2 Years for Manslaughter.” Blytheville Courier News, April 8, 1971, pp. 1, 4.

Mid-South Oral History Collection. Archives and Special Collections, Dean B. Ellis Library. Arkansas State University, Jonesboro, Arkansas.

Mississippi County Nurse Midwife Collection. Archives and Special Collections, Dean B. Ellis Library. Arkansas State University, Jonesboro, Arkansas.

“Scattered Fires Break City’s Quiet.” Blytheville Courier News, September 2, 1970, p. 1.

“Schools Remain Open, 40 Protesters Jailed.” Blytheville Courier News, April 16, 1971, pp. 1, 5.

“Students Returning.” Blytheville Courier News, April 23, 1971, pp. 1, 6.

“White Grocer Is Charged in Slaying.” Blytheville Courier News, August 29, 1970, pp. 1, 2.

Charles Baclawski

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Thank you for this information. During this time I was an 8th grader at Blytheville East Junior High – Home of the Braves. I knew one day we had to leave school because of a bomb threat. I don’t understand why my mother didn’t talk to me about what was going on. She had told me her father told her she would be less prejudiced against black people than he was and her children would be less prejudiced than she was. I cried tears of joy when Barack Obama was elected president. I thought our country had turned a major corner in outgrowing racism. I was so wrong. Trump came along and made it okay for the festering hatred to crawl out from where it hid.

I want to honor Mr. Cecil Brown, a most excellent man and a great band director. He must have suffered after moving from being Harrison High’s band director to leading a motley crew of kids in a portable building at East Junior High. It truly was a shame that the rich traditions of black Harrison High’s Marching Band were relegated to history. Mr. Brown’s high school band members danced down Blytheville’s streets in parades. Some of us Mr. Brown taught in junior high couldn’t tell right from left much less learn our half time routines. But Mr. Brown showed us professionalism, kindness, and patience and taught us that it’s often the emptiest wagons that make the most noise.