calsfoundation@cals.org

Attack on the Steamboat Empress

Confederate troops opened fire on the unarmed steamboat Empress as it passed Gaines’ Landing in Chicot County on the Mississippi River on August 10, 1864, killing and wounding several soldiers and civilians.

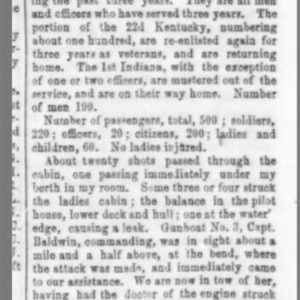

The steamboat Empress, under the command of forty-year-old Captain John Molloy, a native of Ireland, left New Orleans on August 6, 1864, to steam up the Mississippi River to St. Louis, Missouri. There were around 200 soldiers aboard, including members of the Twenty-second Kentucky Infantry Regiment who were heading home on furlough after reenlisting, the First Indiana Heavy Artillery who had completed their terms of service, and other men who had recently been prisoners of war in Confederate camps. Around 150 civilians boarded the vessel and another 150 would be picked up as the Empress headed north, including around sixty women and children.

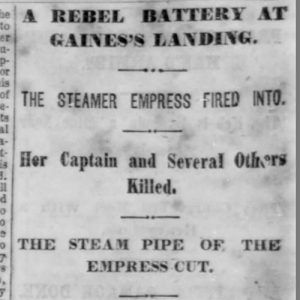

As they neared Gaines’ Landing, smoke from the steamboat could be seen rising above the trees. Around 1,000 of Brigadier General John Sappington Marmaduke’s Confederates, along with a pair of masked batteries with ten cannon between them, were hidden on the riverbank as the Empress approached between 3:00 and 3:30 p.m. on August 10, 1864.

The Confederate artillery opened fire, and a passenger on the Empress wrote that “the first shot was fired from a rifle cannon, and then followed a storm of shot, shell and minie balls, which lasted twenty-five minutes.” Colonel George Currie, who had just resigned as commander of the Mississippi Marine Brigade, was in the vessel’s wheelhouse and said Marmaduke’s troops began shooting “volley after volley of musketry at short range, while the Artillery kept up a constant and rapid firing, each shot perforating the boat’s cabin and sweeping the deck.” An account in the Washington Telegraph said that “the scene among the passengers was one of indescribable terror.”

A Confederate writing about the attack reported that “the sudden burst of fire shocked her so greatly she stopped her engines and rang the bell furiously,” while Currie wrote that he ordered the vessel, which had a paddle wheel disabled, to keep going amid some calls for the Empress to sound its whistle and surrender. Molloy was on the Texas deck and “a cannon ball…struck him in the back of the neck just above his shirt collar and took off his head as sharply as if done with an axe.” A passenger was standing “alongside of a soldier who had his head shot off and was covered from head to foot with blood and brains.”

A Federal artilleryman aboard the Empress “says he never saw guns so well served before, and it is wonderful no more execution was done under the circumstances,” while a passenger wrote that “it was the most rapid firing I have ever heard, in many instances not one second apart.” The boat was hit by as many as sixty-three Confederate cannonballs.

The steamboat had a large number of mules aboard, which shielded the vessel’s boilers from the Confederate cannon fire, though many of the animals were killed. Passengers and soldiers hid behind piles of luggage, and “a large quantity of baggage was destroyed; trunks were torn open and shot to pieces, and in several spent balls were found imbedded in the clothing.”

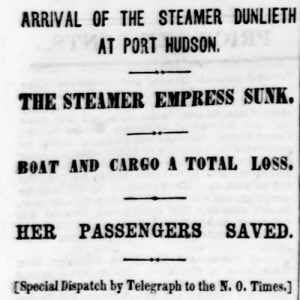

As the Empress began to drift powerless down the river, the USS Romeo noticed its plight. Captain Thomas Baldwin reported that “we got up anchor and went to her assistance; fired five shots at the enemy and then took Empress in tow, she being disabled.” A passenger noted that the warship “arrived just as we were getting out of range and danger from the assassins.” The Union tinclad towed the crippled steamer to the Mississippi shore about five miles above Gaines’ Landing.

In addition to Molloy, three soldiers and a civilian were killed in the attack on the Empress, while twelve people were wounded. (One Confederate was killed, and three or four were wounded in the action.) All but Molloy were buried on the Mississippi shore while the vessel was repaired; the steamboat captain’s body was taken to St. Louis and buried in Calvary Cemetery. He was remembered as “a noble fellow, an honor to that worthy class who follow the precarious fortunes of the river for an occupation” and “an old and esteemed favorite with the traveling and shipping community.” The Empress was repaired and then continued north early on August 11.

The USS Prairie Bird arrived at the scene of the attack on the afternoon of August 11, 1864, and at 3:10 p.m. “commenced shelling woods at Rowdy Bend.” Twenty-five minutes later, Commander Thomas Burns reported, “the enemy opened fire from masked battery of three or four guns and a large force of musketry….When abreast, they opened from more guns. The firing was very rapid from the enemy.” The Romeo arrived and began shelling the woods before both gunboats retired. A Confederate wrote that “the engagement lasted half an hour, when the gunboat backed out, afraid to expose her wheel…and retired amid the shouts and jeers of the command.” The Prairie Bird was hit by twenty-one cannon balls during the engagement. George Matthews, a Black sailor, was killed, and four men were slightly wounded in the fighting.

For additional information:

“Affair at Gaines Landing.” Washington Telegraph, August 31, 1864, p. 2.

Edwards, John N. Shelby and his Men: or The War in the West. Cincinnati, OH: Miami Printing and Publishing, 1867.

“Full Details of the Attack on the Steamer Empress.” Daily True Delta, August 16, 1864, p. 1.

“Full Particulars of the Attack on the Steamer Empress.” New Orleans Times, August 16, 1864, p. 2.

“John Molloy.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/51620889/john-molloy (accessed December 19, 2024).

“More about the Empress.” Times-Picayune, August 19, 1864, p. 1.

“Perils of the Mississippi.” New Orleans Times, August 31, 1864, p. 6.

“A Rebel Battery at Gaines’s Landing.” New Orleans Times, August 15, 1864, p. 1.

“River Intelligence.” New Orleans Times, August 15, 1864, p. 8.

Simons, Don R. In Their Words: A Chronology of the Civil War in Chicot County, Arkansas and Adjacent Waters of the Mississippi River. Lake Village, AR: D. R. Simons, 1999.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. 41, Part 2. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1893, pp. 583, 773, 784, 1085.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies. Vol. 26. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1914, p. 504–508.

Mark K. Christ

Little Rock, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.