calsfoundation@cals.org

Aluminum Bowl

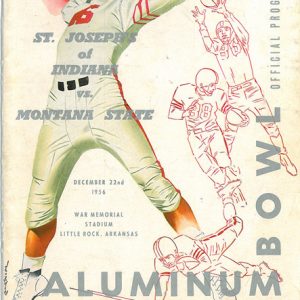

On December 22, 1956, War Memorial Stadium in Little Rock (Pulaski County) hosted the Aluminum Bowl football game. The game pitted Montana State College against St. Joseph’s College of Indiana in the first national football championship game of the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA). The NAIA governs hundreds of small college athletic programs across the United States.

The Aluminum Bowl marked two historic events in Arkansas. It was the first time that a national collegiate football championship game was played in Arkansas, and it is thought to be the first racially integrated college football game to be played in the state. In an era of tense race relations across the South, the game came to Little Rock due to its organizers’ willingness to break the color line that existed in Arkansas collegiate athletics.

Several months prior to the 1956 college football season, interested parties in Tennessee, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Arkansas explored the possibility of hosting the inaugural NAIA championship game. By March, a group from Shreveport, Louisiana, appeared poised to ink a deal with the NAIA in order to bring the game to Shreveport. In July, however, the Louisiana legislature passed a bill banning integrated sporting events in the state.

Consequently, the NAIA was compelled to search for another city to host the game, since some of their member colleges had African-American athletes. Thus hopes of bringing the game to Little Rock were revitalized. Allen Berry, the general manager of War Memorial Stadium, spearheaded an effort to rally the resources of local businesses and industries in order to secure an agreement with the NAIA.

Soon, the Little Rock Chamber of Commerce raised the necessary guarantee of $25,000 to ensure backing for the game. By November, the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) and the Reynolds Metals Company had agreed to pay $25,000 each to the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) to broadcast the game. In total, 200 CBS affiliate television stations, 255 CBS radio stations, and Armed Forces Radio carried the broadcast. Furthermore, the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) agreed to carry the game in markets not served by CBS.

The Alcoa and Reynolds companies, both with strong ties to Arkansas, viewed the game as an opportunity to advertise their industry and its products. Local organizers viewed the game as an opportunity to promote the state of Arkansas. In the weeks and days preceding the game, daily press releases and feature articles promoted the game extensively. In addition, dozens of towns and cities from across the state were slated to participate in Aluminum Bowl festivities.

A variety of events and celebrations, including marching bands and floats, promoted the industries, ingenuity, and talent of Arkansas. At halftime, the featured event included Miss Arkansas, Barbara Banks, wearing a $25,000 dress made out of aluminum as she introduced Governor Orval Faubus to the national television audience. The game itself, however, was nothing short of a disaster.

Despite the best efforts of the organizers to blunt its effects, the weather was miserable and dominated the day’s storyline. Soaking rains plagued the ballgame and the performance of both teams. Furthermore, only 5,000 people came out to see the game, leaving 33,000 seats empty. At halftime, Miss Banks was bundled to the neck in a coat to protect the aluminum dress from the rain. The game ended in a disappointing scoreless tie. After the two teams agreed to share the trophy, a coin flip at a post-game banquet determined which team would possess the trophy for the first six months.

Off the field, both teams soon suffered the indignities of segregation. Upon arriving in Little Rock, the Montana State team had been welcomed by Aluminum Bowl officials with pomp and fanfare. Later, however, the players were alarmed to learn that one of their teammates, an African American named Charlie Jackson, was assigned to stay in a hotel miles away from his teammates. The same fate met an African-American player and a trainer from the St. Joseph’s team when they arrived at their hotel in Hot Springs (Garland County).

Berry and his fellow Aluminum Bowl organizers subsequently failed to keep the game in Little Rock, and the opportunity to host a national event proved to be elusive. In 1957, the championship game, renamed the Holiday Bowl, was played in St. Petersburg, Florida. Bringing the game to Little Rock, however, did reveal a shifting attitude toward segregation. At the same time, the experience shared by the players and staff of both teams was a reminder that much work remained to be done in the realm of civil rights in Arkansas.

For additional information:

“Aluminum Bowl Game Here December to Be On National TV, Radio.” Arkansas Gazette. November 4, 1956, p. 3B.

Burton, Freddie, comp. “The Original Aluminum Bowl.” The Saline 37 (Spring 2022): 20–25.

Keady, Jack. “Rain Blocks Perfect Game in Bowl Opening.” Arkansas Democrat. December 23, 1956, pp. 1A, 1B.

“NAIA Crown to Top Festive Fare Today at Aluminum Bowl.” Arkansas Gazette. December 22, 1956, pp. 1A–2A.

“See You in Little Rock.” The N.A.I.A. News, December 1956, pp. 1, 4.

Paul Edwards

Boston, Massachusetts

Is there any remaining film of this game? I had two uncles on the Montana state team: Frank and Jim Landon.

I was the sports information director for St. Joseph’s College when the Pumas played in the Aluminum Bowl game in 1956. My clearest memory of the game was sitting next to the Chicago Tribune sports writer; he was furious because he couldn’t see the numbers on the jerseys because they were covered with mud. I couldn’t read the numbers either, which made him even more furious. I managed to identify the St. Joe players as well as I could, but it was a mess. I’ve always thought, though, that the game was a terrific defensive battle played between the 25-yard lines. The players fought their hearts out under virtually impossible conditions, and my recollection iswithout benefit of statisticsthat the punting was superb. These were two excellent teams, and, in a way, I thought a scoreless tie was (given the conditions) the most appropriate outcome. I was twenty-five years old and a journalism graduate of Marquette University. St. Joseph’s was my first full-time jobI was also a journalism instructor, a news director, and the editor of the monthly alumni publicationand the Aluminum Bowl was a real challenge. I did more than one all-nighter writing feature stories on the players for their hometown newspapers, among other tasks. It was a shame that a violation of the civil rights of black high school students forced this significant new bowl game out of Arkansas. But I was able to make the most of it: the thesis for my master’s degree at Marquette was a content analysis of the coverage by the two Little Rock newspapers of the civil rights story in 1957. (My final conclusion: The Arkansas Gazette was clearly the more professional and courageous of the two.) I received a Master of Arts in journalism from Marquette in 1960.