calsfoundation@cals.org

Toll (Lynching of)

The only documented lynching recorded in Saline County occurred on October 23, 1854, when a slave known only as “Toll” was murdered by a mob. He was hanged on a hill near the Saline County Courthouse in Benton. Recent scholarship has argued that the Toll lynching was not a spontaneous event but was instead an organized act of vengeance.

The man known as Toll—spelled “Tol” in the Arkansas Gazette—was a slave owned by Scottish-born Samuel McMorrin, who, at the time, was living in Fourche Township in Pulaski County. Reportedly, in 1853, Toll sneaked up on and shot two white men, Jessup McHenry and John Douglas, who were deer hunting about fifteen miles outside of Little Rock (Pulaski County). Toll was arrested and then indicted by a Pulaski County grand jury that December. McMorrin, Toll’s owner, wanted a fair trial for his slave. Whether McMorrin believed Toll to be innocent, or was just protecting his property, is unclear, but he did pay Toll’s legal fees.

The trial was delayed due to the difficulties of assembling a jury, and then the proceedings were later moved, along with Toll himself, to Benton because the attempt to bring in an out-of-town witness had further delayed the start of the trial by six months. Samuel McMorrin died while Toll was in jail at Benton. His wife kept up the fight for a trial, to no avail.

While Toll was being held in the Saline County jail by Sheriff William Ayers Crawford, a mob of reportedly more than 100 white citizens overpowered Sheriff Crawford and his deputy before taking Toll from the jail and hanging him from a nearby tree. Toll proclaimed his innocence until his death.

Reports differed on what really happened between Toll and the two men he was accused of shooting in 1853, as well as the circumstances surrounding Toll’s death. The Arkansas Gazette did not cover the events until October 27, 1854, under the title “Mob and Murder in Saline County.” That article alleged that Toll shot and killed McHenry and Douglas “near the Southern Road, some ten or twelve miles from this place.” Douglas is reported to have died, while McHenry was severely wounded but had recovered. According to the article, the evidence against Toll, while, “entirely circumstantial went far towards establishing the presumption that he was guilty of the murder with which he was charged.” Furthermore, by October 27, 1854, fifteen months after the fact, Toll’s health “was so bad as to make it almost certain that he would not live until the next term of the court.” The Gazette even noted that Toll had not escaped from Crawford’s jail when he had the chance to do so.

The October 27 report alleged that, while Toll was in jail, “a mob of more than one hundred men, assembled, and in the light of day, and in the presence and defiance of the legal authorities, forcibly broke open the jail, took the accused from his legal custodian, and hung him, [Toll] protesting his innocence of the crime charged to him to the last moment of his life.” The Gazette called the mob “cowardly” and said that it did not believe that Sheriff Crawford could not put down the mob.

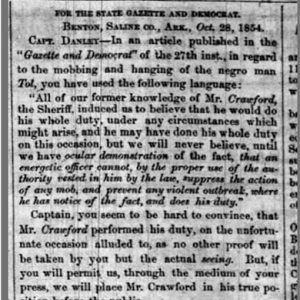

A letter to the Gazette’s editor Captain Christopher Columbus Danley contained a reply to the previous day’s article from citizens of Benton. The reply stated that the mob was composed of “citizens from Pulaski and Saline counties. Their numbers were variously estimated to be 50 to 80 men. All were armed, mostly with double-guns and side-arms.” The crowd came to Benton “at 11 o’clock AM on Monday, 23rd inst., while the citizens were at their usual occupations.” As to the sheriff’s whereabouts, he was said to be transporting a convict to Little Rock before meeting the mob “three miles from Benton,” Crawford apparently asked the mob to disperse before racing to his home for armaments after they had refused.

According to this account, when Crawford and his men arrived at the jail, “four men belonging to the mob seized Mr. Crawford, four more also seized Mr. Thomas Pack, Deputy Sheriff, and in that situation held them until the mob had broken the jail open and seized the body of the negro Tol. They immediately proceeded with the negro to an adjoining hill, and hung him.” The October 28 letter from Benton citizens sought to explain what had happened and correct Danley’s errors. The men who signed their names to it were Joseph Scott, S. M. Sweeten, William Payne, J. A. J. Buents, Ransom Thompson, P. Caveness, Uriah Allen, J. S. Marshall, and P. Link.

On November 3, 1854, Danley issued an apology for his comments about Sheriff Crawford in a column called “The Saline Mob.” In his column, Danley had argued that because Crawford saw Toll’s murderers, he should have had them prosecuted for committing “an unprovoked, a cold-blooded, and a deliberate murder, without one mitigating circumstance.” Danley ended his apology by stating, “We do not wish to dwell or enlarge on the subject. Crime has been committed and the duty of the officers of the law is plain. It remains to be seen whether this mob will be dealt with according to law and whether or not the officers of the law will do their duty.” Members of the mob were never revealed, and no one was ever arrested for Toll’s murder.

For additional information:

“Capt. Danley.” Arkansas Gazette, November 3, 1854, p. 3.

Jones, Kelly Houston. “Doubtless Guilty: Lynching and Slaves in Antebellum Arkansas.” In Bullets and Fire: Lynching and Authority in Arkansas, 1840–1950, edited by Guy Lancaster. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018.

“Mob and Murder in Saline County.” Arkansas Gazette, October 27, 1854, p. 2.

“The Saline Mob.” Arkansas Gazette, November 3, 1854, p. 2.

Cody Lynn Berry

Benton, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.