calsfoundation@cals.org

Paradise Lost

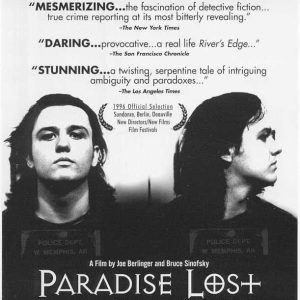

Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills (1996) is a documentary filmed for HBO (but later released into theaters) by Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky dealing with the 1994 trials of three teenagers charged with murdering and mutilating three eight-year-old boys in 1993. The defendants became known as the West Memphis Three because the murders happened in West Memphis (Crittenden County).

The directors spent ten months interviewing those involved with the case. The documentary brought to light inadequacies in the local judicial system and led many to believe that the defendants had been wrongly accused and prosecuted. The film won a Primetime Emmy and was followed by two sequels: Paradise Lost 2: Revelations (2000) and Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory (2011). Paradise Lost 3, which was nominated for an Academy Award, further portrayed the West Memphis Three’s subsequent legal battles and ultimate release. The documentary series has garnered quite a following especially among celebrities, musicians, and artists, including the band Metallica, who allowed their music to be used for the soundtrack, the first time they had allowed this for a film. The attention these films brought to the West Memphis Three led to fundraising efforts for legal defense, including a tribute album and various songs, and many believe that the Paradise Lost series was partly responsible for the 2011 release of the West Memphis Three.

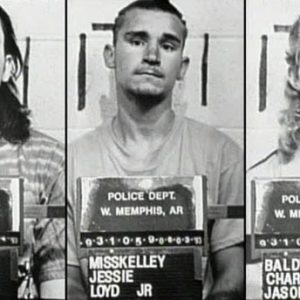

The focus of the first documentary is on the accused teenagers—Damien Echols, Jessie Misskelley Jr., and Jason Baldwin—and the investigation of the crime. After three boys were found murdered and mutilated in a creek bed near West Memphis, many believed that they had been murdered as part of a satanic sacrifice. The three teenagers were convicted, though many elements of the evidence have since been questioned or shown to be false, as revealed through the documentary series. For example, Vicki Hutcheson, a friend of Misskelley’s, later recanted her testimony, claiming police coercion. Misskelley was tried separately and sentenced to life plus forty years in prison. Baldwin and Echols were tried together, Baldwin also receiving life in prison and Echols receiving the death penalty.

In an interview with the Huffington Post, Berlinger stated that his original intent had not been to exonerate the teens; in fact, he and Sinofsky had assumed the West Memphis Three were guilty and only intended to document the grisly facts of the case. Instead, after interviewing families of the victims and investigating the evidence, the filmmakers began to question the public opinion, and after interviewing the defendants, Berlinger and Sinofsky began to suspect that the accused were innocent. Berlinger went on to criticize other news organizations for sensationalizing the events and “telling the lazy story of devil-worshipping teens and satanic murderers.” Berlinger went on to say that he felt a lot of guilt over the success of the first film because the West Memphis Three were still in prison. However, because of their rather unprecedented access to the courtroom and filming of the trial, the filmmakers were able to bring the case to national attention. The film and its sequels, which further investigated the murders, led to a cultural phenomenon and skyrocketed Echols and the others into a kind of celebrity. Though the first film could be seen as tarnishing Arkansas’s image, it did bring to light inconsistencies in the legal system.

With the success of the first film, many artists, musicians, and actors came to the defense of Echols and the others, raising money for their defense and spreading awareness of the film. The second documentary was an attempt to reopen the case. An interesting turn in this documentary focused on John Mark Byers, the stepfather of one of the victims, who vehemently asserted the trio’s guilt even while his own criminal and violent past came to light, along with evidence that seemed to tie him to the murders. The third film covered the eventual release of the trio; production was actually wrapping up when the West Memphis Three were released.

Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley each appealed their cases multiple times based on new forensic evidence and were finally released after entering an Alford plea on August 19, 2011, which reduced their sentences to time served.

For additional information:

Costanza, Justine Ashley. “Interview with Paradise Lost Director Joe Berlinger.” Huffington Post, January 28, 2013. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/justine-ashley-costanza/interview-with-paradise-l_b_2554124.html (accessed October 31, 2025).

Kompanek, Chris. “Paradise Lost’s Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky.” The A.V. Club, January 11, 2012. https://www.avclub.com/paradise-lost-s-joe-berlinger-and-bruce-sinofsky-1798229206 (accessed October 31, 2025).

Leveritt, Mara. “Documentary Examines Arkansas Witch Trials.” Arkansas Times, June 15, 1996, p. 16.

———. “Fame and Damien.” Arkansas Times, October 11, 1996, pp. 8–9.

Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills. Internet Movie Database. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0117293/ (accessed October 31, 2025).

Paradise Lost 2: Revelations. Internet Movie Database. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0239894/ (accessed October 31, 2025).

Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory. Internet Movie Database. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt2028530/ (accessed October 31, 2025).

C. L. Bledsoe

Wynne, Arkansas

The key to the whole story is the failure of the police to arrest the black man at Bojangles Restaurant.