calsfoundation@cals.org

Indochinese Resettlement Program

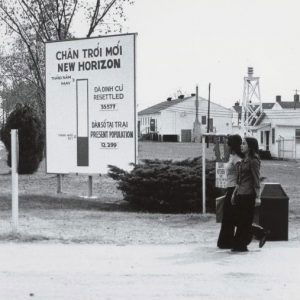

aka: Operation New Life

In 1975, the state of Arkansas was tapped by the federal government to be one of four main entry points for Indochinese refugees. The presence and availability of the facilities at Fort Chaffee, located adjacent to Fort Smith (Sebastian County), made it an ideal location for processing tens of thousands of Indochinese seeking refuge from their war-torn country.

When the United States evacuated its remaining personnel from Vietnam in the spring of 1975, it left in its wake a wide segment of the Indochinese population who had assisted the American military and political effort. Without the American presence, they were left vulnerable to retaliation by the North Vietnamese government. Many fled in the days and weeks leading up to the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975. Those who did not make it out by plane before the fall of Saigon either fled by dangerous methods such as boat or attempted to walk to safety. Many were captured and sent to so-called reeducation camps that were in essence concentration camps.

The 1975 Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act (PL94-23) was one congressional response to this humanitarian crisis. The act aimed to assist Indochinese in escaping the danger they faced from the North Vietnamese government and finding them safe residences in the United States. There were four points of entry for refugees into the United States, including Camp Pendleton in California, Eglin Air Force Base in Florida, Fort Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania, and Fort Chaffee in Arkansas. At Fort Chaffee, the project was referred to as “Operation New Life.”

The U.S. Army was notified on April 25, 1975, that Fort Chaffee would be used as a relocation center, and the first Indochinese arrived at Fort Chaffee just seven days later on May 2, 1975. The first plane carried seventy refugees, and they were met by a handful of dignitaries, including Governor David Pryor. Within twenty-two days, there were 25,812 refugees, which made the fort effectively the eleventh-largest city in the state. By the last day of the program just seven months later, on December 20, 1975, 50,809 refugees had been processed through Fort Chaffee.

The Indochinese population that arrived was a very heterogeneous one, consisting of Vietnamese, Laotian, Cambodian, and Hmong. From the local perspective, however, they were often mistakenly perceived to be one homogenous cultural group. Compared to the documented and undocumented immigrants fleeing their country of origin due to poor economic times, such as the Irish during the potato blight of the 1840s or Latinos in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, this is a very different group. As many were political refugees, they were granted permanent, legal residence in the United States.

Refugees were quickly rotated out of Fort Chaffee as sponsors or host families around the United States were secured. Many agencies worked to this end. The United States Catholic Conference alone found sponsors for 20,000 of the refugees. At the peak of the airlift, some days saw as many as seventeen flights landing at Fort Smith Municipal Airport. There were 415 flights in total. By June 14, 1975, there were 6,500 Army Reserve personnel working at the fort. It is estimated that several millions of dollars were pumped into the local economy as a result of the relocation program.

The American responses to these refugees were as mixed as the American response to the Vietnam War in general. Local reactions to the anticipated arrival of tens of thousands of Indochinese refugees went from one extreme to the other. Newspaper accounts from the eve of their arrival reflect a range of responses from the xenophobic and racist to the hospitable and charitable. While some actively protested the refugees’ presence—citing fears that Fort Chaffee would become a permanent residence for the refugees, who might then take away jobs from the local population—others fully supported efforts to assist in educating the refugees and helping them make a life in Fort Smith. Indeed, many of the refugees became on good terms with the local population as families sponsored them, and some married into the local Fort Smith population.

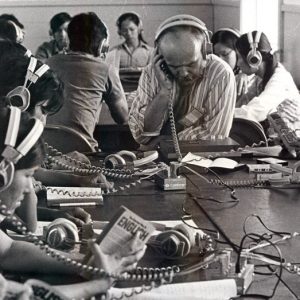

There was an active effort at Fort Chaffee to assist the refugees in making the transition to living in the United States. On May 4, 1975, two days after the first refugees’ arrival, a Vietnamese newspaper, the Tan Dan, began publication. On October 16, 1975, a bilingual radio station, K224AG/FM, was established to broadcast information to the refugees. The local college, Westark Community College (now the University of Arkansas at Fort Smith), set up classes for teaching English. In addition to education programs, forms of entertainment were provided, such as a rodeo and an Independence Day celebration intended to help acclimate the new arrivals to American ideals.

Life at Fort Chaffee was at moments quite difficult for refugees. On June 20, 1975, a group of eighty Vietnamese held a demonstration to let their frustration be known at what they felt to be a long time waiting to be processed. Two days later, a second demonstration was held by 600 refugees. This time, however, it was in counter to the previous protest, thanking the Americans for all that they were doing to assist them. Additional strain was created at the fort because several top-ranking South Vietnamese government officials were among the refugees. Some refugees could not contain the animosity they felt toward these officials who, they felt, had lost their country to the North Vietnamese. Overall, the Provost Marshal report indicates that the refugees were the perpetrators and victims of cases of five rapes, twenty-two cases of aggravated assault, 266 cases of larceny, and two suicide attempts. There were 517 offenses in all, less than half of which, 212, were perpetrated by the refugees. Operation New Life took on literal meaning as there were 325 children born to refugees at the fort during this short stay. Life for the refugees at Fort Chaffee mirrored the life of a real city.

A small fraction of the total refugees who went through Fort Chaffee made their home in Fort Smith, as most were relocated to other states. As the 1975 refugees found their niche in Fort Smith, subsequent migrations of Indochinese found their way to the city. In the 1980s, additional programs of the United States assisted more individuals in escaping the fallout of the war. With an established Indochinese population, Fort Smith was an attractive choice for some of these later refugees.

In 2002, the University of Arkansas at Fort Smith conducted oral history interviews with refugees, military personnel, and relief agency staff to document and preserve this moment in the history of Fort Chaffee and its local and national impact. In the 2000 Census, there were only 4,039 Asian Americans counted in Sebastian County (and this figure includes Asian Americans from places outside of Indochina as well), making up a mere 3.6 percent of the population. But the social landscape of Fort Smith was indelibly changed as the refugees gradually established themselves: Buddhist temples, as well as Vietnamese, Laotian, and Hmong grocery stores and restaurants, opened; business establishments reoriented themselves to accommodate new clientele, featuring signs in Lao or Vietnamese; Vietnamese and Laotian New Year’s celebrations are well-attended annual events; and the native tongues of these refugees are heard often in Fort Smith.

For additional information:

Freeman, James. Changing Identities: Vietnamese Americans 1975–1995. Boston: Allyn and Bacon Press, 1995.

Gallman, Judith M. “Finding Refuge in Fort Smith.” Arkansas Times, November 1991, pp. 34–37, 79–82.

Guerrero, Perla M. “Impacting Arkansas: Vietnamese and Cuban Refugees and Latina/o Immigrants, 1975–2005.” PhD diss., University of Southern California, 2010.

———. Nuevo South: Latinas/os, Asians, and the Remaking of Place. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017.

———. “Yellow Peril in Arkansas: War, Christianity, and the Regional Racialization of Vietnamese Refugees.” Kalfou: A Journal of Comparative and Relational Ethnic Studies 3 (Fall 2016): 230–252.

Lewis, David. Oral History Transcription, History of Westark College. April 26, 2002. Pebley Historical and Cultural Center. University of Arkansas at Fort Smith, Fort Smith, Arkansas.

Lipman, Jana K. “A Refugee Camp in America: Fort Chaffee and Vietnamese and Cuban Refugees, 1975–1982.” Journal of American Ethnic History 33 (Winter 2014): 57–87.

Southeast Asian Relocation Collection. Pebley Historical and Cultural Center, Boreham Library. University of Arkansas Fort Smith, Fort Smith, Arkansas.

Wiggins, Melanie Spears. “Escape to America: Evacuees from Indochina arrive in Fort Smith-1975–1979.” Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 31 (April 2007): 14–29.

Daniel Maher

University of Arkansas at Fort Smith

Buddhist Temple

Buddhist Temple  Buddhist Temple

Buddhist Temple  Fort Chaffee Drawing

Fort Chaffee Drawing  Fort Chaffee Drawing

Fort Chaffee Drawing  Fort Chaffee English Lessons

Fort Chaffee English Lessons  Fort Chaffee Newspaper

Fort Chaffee Newspaper  Fort Chaffee Sign

Fort Chaffee Sign  Fort Chaffee, Aerial View

Fort Chaffee, Aerial View  Fort Smith Vietnamese Restaurant

Fort Smith Vietnamese Restaurant

There is no mention of the military units that supported Operation New Arrivals. I was a member of a platoon, D Company, 5th Engr. Bn. out of Fort Leonard Wood that provided support, specifically the installation of necessary equipment to expand the sewage system to acomodate the influx of the refugee population. The men of the 5th endured extreme heat, humidity, and long hours during its mission. I was extremely proud to have served with exceptional combat engineers who were able to demonstrate their skills during this assignment.

COURAGE, SKILL, STRENGTH

When I was thirteen, our softball team and another team played an exhibition game, then our team had the pleasure of playing the Vietnamese team. No score was really kept and we gave them some equipment. This game has stuck with me forever. We were young. The amazing thing was that we had softball in common and we communicated, not with words but by how we treated each other and played the game, different groups of people coming together for a game… I wish I had pictures.

When the first plane landed on a wet, dreary morning in 1975, I was there. A Vietnam veteran tried to climb the fence to get to them. He had lost both legs in Vietnam and hated the Vietnamese; I had to pull him off the fence. I eventually went to work for the Catholic Conference, which was one of the organizations there to help process the refugees. I’m also a Vietnam veteran.

I also started the first FM commercial radio station ever allowed on a military base. General McMull was the base commander at the time there, and he gave me an empty barracks in the hospital area for the radio station. I sent a Western Union telegram to the White House and invited then-President Ford to come to the opening of the radio station.

I noticed that you included some illegal activities of the Vietnamese, yet nothing was said about City National Bank being banned from Fort Chaffee for embezzling money from the Vietnamese who had brought gold with them to Fort Chaffee. I was also there the day that Father Kwat, leader of the first demonstrators at Fort Chaffee, spoke! My photo was on the front page of SWTR holding the door shut to keep Father Kwat out of the building. They were in fact upset with the slow process but most importantly about the lack of information about our culture and different areas of the country that these refugees were being sent. They actually were sneaking back at night quicker than we could get them sponsored out. I still have a few photos of when President Ford came to Chaffee.

Fort Chaffee 1975; I was a family physician at Fort Belvoir, Virginia in late April of 1975 when I was notified that I would be sent to Fort Chaffee Arkansas to care for Vietnamese refugees. Other medical personnel soon arrived from multiple bases until there were twelve physicians and forty nurses. In addition, a complete field hospital unit was brought from Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Fort Chaffee was a mothballed World War II camp which had been modestly maintained. After two or three days of scrubbing beds and mattresses refugees began arriving. Within a week the stream of refugees was more than a thousand per day. The twelve physicians were responsible for intake examination, emergency room services, labor and delivery services, pediatric services, and limited surgical services. I was assigned to labor and delivery under the leadership of Ronald S. Gibbs, MD. Ron and I shared the responsibility for about a hundred deliveries. Our pediatric unit of 30 beds was constantly full with hard measles – rubeola. My little two year old patient developed a secondary lobar pneumonia which we recognized, treated and had a successful outcome. A different two year old died as a result of his measles infection. The close crowding of these refugees for two or three days aboard aircraft prior to arrival in the United States was a powerful incubator for the measles virus. I grew to appreciate the good humor and resilience of this refugee population. They experienced many hardships during their escape, transport and encampment. Yet they were friendly and positive. We located several Vietnamese medical students who were very helpful.