calsfoundation@cals.org

Diphtheria

Diphtheria is a serious contagious disease caused by toxin-producing strains of the bacteria Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Typically occurring in childhood, diphtheria is transmitted from person to person through respiratory droplets or contaminated surfaces. The symptoms appear following an incubation period of two to five days and include fever, chills, sore throat, fatigue, and swollen lymph glands in the neck. The formation of an adherent, thick, grayish pseudomembrane in the throat distinguishes the disease. Respiratory diphtheria can be fatal due to either respiratory obstruction or heart and kidney failure. Cutaneous diphtheria is a skin infection that rarely causes serious systemic illness. Recovery does not confer lifelong immunity.

In 400 BC, the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates provided an early description of diphtheria. It was not until the nineteenth century, however, that physicians advanced their understanding of the disease. In 1821, the French physician Pierre-Fidèle Bretonneau was the first practitioner to distinguish diphtheria clinically. Bretonneau’s name for the disease was derived from the Greek word diphthera meaning “leather membrane.” In 1883, the German bacteriologists Edwin Klebs and Friedrich Loffler discovered the diphtheria bacillus. In 1888, the French bacteriologists Alexandre Yersin and Emile Roux demonstrated that the diphtheria toxin caused the symptoms of the disease.

Developed by the German bacteriologist Emil von Behring and others in 1890, the diphtheria antitoxin was the first effective medical treatment for the disease. Arkansas physicians soon became aware of the new treatment. In 1895, the Journal of the Arkansas Medical Society advertised the diphtheria antitoxin. In 1896, Dr. William Blackwell Welch noted that “the weight of [medical] opinion is…largely in favor of the early use of…[the diphtheria antitoxin].” In 1908, Dr. Charles Callaway Price of Douglas (Lincoln County) reported “the actual saving of [a] child’s life [with] one injection” and urged physicians to “keep on hand a liberal supply of [the] anti-toxin.”

Introduced in 1913, the Schick test enabled physicians to assess patients’ susceptibility to diphtheria. First produced in the early 1920s, the diphtheria toxoid was a weakened, but still immunogenic, form of the toxin. In 1926, British researchers added alum to enhance the toxoid’s effectiveness.

In the early 1930s, school-based diphtheria immunizations began in Arkansas. In 1928, Arkansas recorded 564 cases of diphtheria and 139 deaths from the disease. In 1929, the city of Little Rock (Pulaski County) recorded thirty-one diphtheria cases and seven deaths.

In February 1930, the Little Rock School Board (LRSB), the Parent Teacher Association (PTA), and local physicians organized “Diphtheria Prevention Week.” Dr. Corydon M. Wassell, who served as the director of the Pulaski County health department, conducted free diphtheria vaccination clinics for five- to eight-year-old students. A total of 899 students received free diphtheria vaccinations. Private physicians vaccinated 766 students.

In November 1930, more than 2,000 preschoolers and elementary students received diphtheria vaccinations during the Little Rock schools’ second immunization drive. In 1931, the LRSB required all entering elementary and middle-school students to receive diphtheria vaccinations. The health department provided free immunizations for families unable to afford the service. In November 1932, Wassell, the LRSB, and the PTA offered diphtheria immunizations to one- to twelve-year-olds for “a small maximum charge.”

In 1934, American Legion members in Little Rock held free diphtheria vaccination clinics for poor children, which were later opened to all children. (The American Legion is a nonprofit military veterans’ organization that serves communities and service members.) Clinic organizers reported that 759 children received vaccinations.

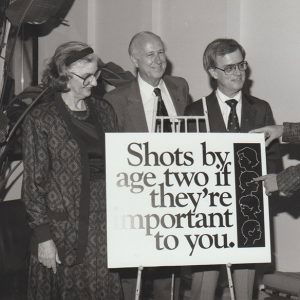

Beginning in the late 1940s, use of the DPT—combined diphtheria, pertussis (a.k.a. “whooping cough”), and tetanus—vaccine hastened diphtheria’s decline in the United States; the number of reported cases of the disease dropped from 147,991 in 1920 to 918 in 1958. Between 1959 and 1970, Arkansas and other southern states continued to experience high rates of diphtheria, however. In 1973, Arkansas first lady Betty Bumpers’s “Every Child By ’74” campaign addressed the state’s low childhood immunization rates.

Between 1980 and 1994, the United States recorded only forty-one diphtheria cases. In the 1990s, the DTaP (combined diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis) vaccine replaced DPT because of the adverse reactions associated with the whole-cell pertussis component.

As per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) childhood vaccination schedule, the Arkansas Department of Health (ADH) recommends that children receive their first dose of DTaP at two months, the second at four months, the third at six months, the fourth at fifteen to eighteen months and the fifth at four to six years. Adults should receive the lower-dose Tdap booster every ten years. In the twenty-first century, the very few recorded cases of diphtheria that occur in the United States are associated with unvaccinated individuals and international travel.

For additional information:

“759 Immunized at Diphtheria Clinic.” Arkansas Gazette, April 4, 1934, p. 20.

Acosta, Anna M., Pedro L. Moro, Susan Hariri, and Tejpratap S. P. Tiwari. “Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Pink Book Chapter 7: Diphtheria.” http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/dip.pdf (accessed March 16, 2023).

Arkansas Department of Health. “Immunizations.” https://www.healthy.arkansas.gov/programs-services/topics/immunizations (accessed March 16, 2023).

Bisgard, Kristine M., Ian R. B. Hardy, Tanja Popovic, Peter M. Strebel, Melinda Wharton, Robert T. Chen, and Stephen C. Hadler. “Respiratory Diphtheria in the United States, 1980 through 1995.” American Journal of Public Health 88 (May 1998): 787–791.

Brooks, George F., John V. Bennett, and Roger A. Feldman. “Diphtheria in the United States, 1959–1970.” Journal of Infectious Diseases 129 (February 1974): 172–178.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Immunization Schedules.” https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/index.html (accessed March 16, 2023).

Chen, Robert T., Claire V. Broome, Robert A. Weinstein, Robert Weaver, and Theodore F. Tsai. “Diphtheria in the United States, 1971–81.” American Journal of Public Health 75 (December 1985): 1393–1397.

Colgrove, James. State of Immunity: The Politics of Vaccination in Twentieth-Century America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

“Diphtheria Antitoxin.” Journal of the Arkansas Medical Society 5 (May 1895): 383.

“Diphtheria Immunization of Children Available through Little Rock Voiture, 40 & 8.” Arkansas Gazette, March 13, 1934, p. 6.

“Diphtheria Prevention Week.” Arkansas Gazette, February 2, 1930, p. 4.

“Diphtheria Shots to 1,665 Children.” Arkansas Gazette, February 9, 1930, p. 5.

Hammonds, Evelynn Maxine. Childhood’s Deadly Scourge: The Campaign to Control Diphtheria in New York City, 1880–1930. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

“Immunization Is Health Measure.” Arkansas Gazette, November 30, 1930, p. 13.

“Immunization Is Urged for Pre-School Child.” Arkansas Gazette, March 2, 1930, p. 13.

Price, C. C. “Sporadic Cases of Diphtheria.” Journal of the Arkansas Medical Society 5 (September 15, 1908): 105–106.

“Pupils Must Take Diphtheria Shots.” Arkansas Gazette, November 29, 1931, p. 8.

“Urges Aid During Diphtheria Week.” Arkansas Gazette, November 16, 1930, p. 14.

Welch, William B. “Serum Therapy.” Journal of the Arkansas Medical Society 6 (March 1896): 393–402.

Melanie K. Welch

Mayflower, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.