calsfoundation@cals.org

Danville Lynching of 1883

On September 8, 1883, two white men were forcibly taken by a mob from the jail at Danville (Yell County) and hanged from a bridge spanning the Petit Jean River.

In all the stories recounting this lynching, the two victims are identified only as Dr. Flood and John Coker. One possible match for a “Dr. Flood” is John Flood, recorded in the 1880 census living in nearby Montgomery County with his wife and five children aged two to ten. He was fifty-four years old at the time of the census. The census also records a John Coker, age twenty-nine, working as a farmer and living in Ward Township, east of Danville, with his wife and young son and daughter.

According to the first report on the event in the Arkansas Democrat, “Coker was the cause of the death of young Carter, and Flood harbored the Daniels boys, making many threats.” The “Daniels boys” were outlaws Jack and Bud Daniels, who were alleged to have murdered one William Potter, as well as two other men identified only as “Carter and Caldwell.” How Flood and Coker were affiliated with these individuals is not entirely explained in the reports, but there were many stories on the exploits of the Daniels brothers and their associate, Rial Blocker (or Blocher), whose activities were of such notoriety that Governor James Henderson Berry issued a reward for their capture.

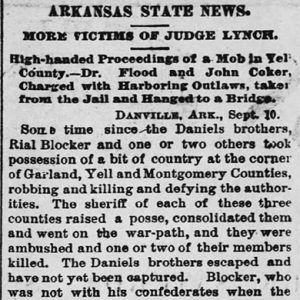

The Arkansas Weekly Mansion provides a more detailed account, noting that the Daniels brothers, Rial Blocker, and a few others “took possession of a bit of country at the corner of Garland, Yell and Montgomery Counties,” referred to as the Three-Corner territory, “robbing and killing and defying the authorities.” Several weeks before the lynching took place, the sheriffs of these respective counties formed a posse and “went on the war-path” against the gang but were ambushed, resulting in the death of “one or two of their members.” Apparently, one of the victims of the ambush was named Carter. The Daniels brothers escaped, but Blocker later surrendered, while “Dr. Flood, who harbored the desperadoes, and John Coker, also charged with the same offense and being in the ambush, were arrested and taken to the jail at Danville.” According to a report printed in the Southern Standard of Arkadelphia (Clark County) and other newspapers, Coker “was the man who led the Sheriff’s posse into a fatal ambuscade while pretending to pilot them in pursuit of the outlaws.”

The Arkansas Weekly Mansion contains the most detailed account of the lynching. On the night of September 8, the jail was being guarded by two young men named Carter, “not related to the Carter who was one of the victims in the ambush.” A mob of fifteen masked men, all mounted on horseback, “came from the east, hitched their horses in the suburbs, and then marched straight to the jail.” They ordered the guards to open the jail, but the guards refused, and so the mob “broke in the doors with crowbars and axes.” The mob found Blocker “praying for his life” but told him to “dry up your blubbering, we don’t want you, for the law will break your neck soon enough.” The mob grabbed Flood and Coker, the latter fighting desperately and begging to be shot rather than hanged, while Flood “maintained a sullen silence and had little or nothing to say one way or another.” The two men were hanged from the center span crossbeam of the iron bridge across the Petit Jean River.

In response to the lynching, Gov. Berry offered “a reward of $200 each for the arrest of the lynchers,” while also increasing the reward offered for the Daniels brothers to $750 each. The Arkansas Democrat, in a September 19 editorial, endorsed the reward and denounced the mob thusly: “If they did not scruple to take the lives of these men who were only charged with befriending murderers, why should they hesitate to hang men who denounce their lawless acts?” However, no members of the mob were ever identified or brought to justice. A few days later, the Arkansas Gazette followed with its own condemnation, insisting that mob law “means simply, punishing crime by committing crime.” An anonymous letter from Danville published in the Gazette on October 12 insisted that “there is no doubt that every member of the mob who hung Flood and Coker, lives either in the town of Dardanelle or in the near vicinity. And the same may be said of those who hung Bruce, Taylor and Holland two years ago,” referring to three men killed in previous lynchings.

On September 10, Blocker managed to escape while the bodies of Coker and Flood were being buried. He was recaptured a few days later by a man named Joe Reed and placed in the jail at Dardanelle (Yell County). In late October, however, he escaped that jail with an indicted murderer named Underwood.

For additional information:

“$4500 Reward!” Arkansas Gazette, September 13, 1883, p. 5.

“Arkansas News.” Arkansas Weekly Mansion, September 22, 1883, p. 2.

“Arkansas State News.” Batesville Guard, September 26, 1883, p. 4.

“The Danville Lynching.” Arkansas Gazette, September 12, 1883, p. 5.

“The Dare Devils.” Arkansas Gazette, July 10, 1883, p. 5.

“Driven Out.” Fayetteville Weekly Democrat, August 9, 1883, p. 2.

“Hanged.” Arkansas Democrat, September 10, 1883, p. 1.

“Honor to Whom Honor Is Due.” Arkansas Gazette, October 12, 1883, p. 3.

“Mob Law.” Arkansas Gazette, September 25, 1883, p. 4.

“The Murderers Underwood and Blocker Break Jail.” Arkansas Gazette, October 25, 1883, p. 1.

“The Outlaws.” Arkansas Democrat, August 1, 1883, p. 4.

“Recaptured.” Arkansas Democrat, September 28, 1883, p. 4.

“Rial Blocher Escapes.” Arkansas Gazette, September 12, 1883, p. 1.

“The Rule of the Mob.” Arkansas Democrat, September 19, 1883, p. 3.

“Still Defiant.” Arkansas Gazette, July 21, 1883, p. 5.

“The Week’s Doings.” Southern Standard, September 22, 1883, p. 1.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.