calsfoundation@cals.org

Brindletails [Political Faction]

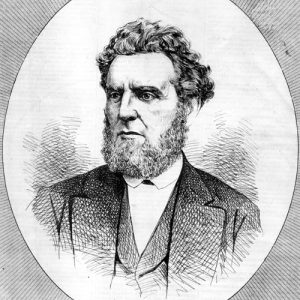

Dissention within the Republican Party of Arkansas began following the 1868 constitutional convention. The schism in the Arkansas Republican Party, like in the national party, threatened to end the party’s political dominance in the state. Two groups within the state party—the Minstrels (aligned with the national regular Republican leadership) and the Brindletails (aligned with the Liberal Republican movement)—emerged. The Minstrel faction, allegedly named due to the past profession of one of its members, relied on newcomers (often pejoratively labeled “carpetbaggers”). Joseph Brooks, who broke with Governor Powell Clayton and the political machine under his control, formed a faction of the Republican Party known as the “Brindletails,” named because his voice was said to sound like a Brindletail bull.

Brooks criticized what he saw as moderate positions under Governor Clayton and pushed for greater governmental intervention in the economy and in society. In the 1870 legislative election, Brooks helped organize an anti-Clayton slate of candidates and ran for the state Senate from Pulaski County; initially seated, he was removed when the Senate reversed itself and seated his Democratic opponent, Wilshire Riley.

In 1872, Brooks was nominated to run for governor by a Brindletail convention, aligned with the Liberal Republican faction whose nominee for president was Horace Greeley. The faction received a great deal of support from African-American voters as well as a significant amount of support from Democrats. Ironically, Brooks was an outsider, or “carpetbagger.” He ran on a platform of ending the corruption of the Clayton regime. He attracted ex-Confederate support by promising re-enfranchisement, and he proposed economic policies more radical than those supported by Clayton. Brooks had been one of the most outspoken members of the 1868 constitutional convention on issues involving Reconstruction policy, but now he sought to tear it apart in his effort to win the office of governor.

The Brindletails faced a daunting task to win the election. One serious obstacle was that they did not control the state’s election apparatus. The Clayton machine controlled the process through the governor’s ability to appoint registrars and election judges in the state. When the votes were counted, Brooks received 38,415 votes to Elisha Baxter’s 41,681. Brooks contested the election (the Minstrel faction controlled both houses of the legislature) only to see Baxter declared the winner. In court, Brooks claimed that Baxter had taken the office of governor without authority (Brooks v. Baxter). Nothing came of the case at the time. When Governor Baxter began appointing conservative Democrats to government positions, some supporters turned against him and saw Brooks and the Brindletails as a way to depose Baxter. Brooks found a friendly court to reopen Brooks v. Baxter and declare him the winner. Brooks occupied the governor’s office while Baxter forces set up camp nearby. Fighting occurred around the state, but Little Rock (Pulaski County) remained the center of hostilities. Both sides appealed to President Ulysses S. Grant for assistance. After a tense month, President Grant intervened on May 15, 1874, on the side of Baxter. President Grant appointed Brooks as postmaster of Little Rock following the so-called Brooks-Baxter War.

For additional information:

DeBlack, Thomas A. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Durning, Dan. “Mayor A. K. Hartman and the Brindletails Usurp Little Rock’s 1870 Election, to No Avail.” Pulaski County Historical Review 66 (Winter 2018): 122–140.

Harris, Rodney W. “Outsiders, Scalawags, and Spendthrifts: The Ideological Battle for Post Civil War Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Central Arkansas, 2011.

Moneyhon, Carl H. The Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction on Arkansas: Persistence in the Midst of Ruin. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2002.

Woodward, Earl F. “The Brooks-Baxter War in Arkansas, 1872–1874.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 30 (Winter 1971): 315–336.

Rodney Harris

Pocahontas, Arkansas

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Hartman, Alexis Karl

Hartman, Alexis Karl Joseph Brooks

Joseph Brooks

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.