calsfoundation@cals.org

Bill Wiley (Lynching of)

In late August 1897, an African American man was lynched in Cleveland County for allegedly killing one man and wounding another at a picnic near Kendall’s mill. Newspaper accounts from the time are confusing as to his identity. Some identify him as Bill Wiley, others as Bill Wiley Douglass, Wiley Douglass, or Bill/Will/William Wyatt. All of these names have been used in various assembled lists of lynching events; public records provide no confirmation of any of them. For convenience, he will be referred to as “Wiley” in this article. The date of the lynching is also in question. The Arkansas Gazette gave three dates in three different articles:, Sunday, August 22; Monday, August 23; and Tuesday, August 24. The Pine Bluff Daily Graphic reported that it happened on August 23. Articles published in the Houston Daily Post and the San Francisco Daily Call give the date as August 22.

The earliest report of the Kendall incident appears in the Pine Bluff Daily Graphic on August 22. On Saturday, August 21, a group of African Americans had a picnic near the Kendall mill in Cleveland County. A number of the attendees worked at Kendall’s mill, and when they failed to appear for work, T. T. Johnson, who worked at the mill, went to the picnic to find them. He had an altercation with one of the men, who drew a knife and slit his throat. Later, a white man named C. T. Gray argued with someone and was also knifed. No suspect had been captured, but “the community is aroused and citizens are out searching for him.”

On August 25, the Arkansas Gazette published a story datelined Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), August 24. According to the Gazette, on August 23, two Black men had been arrested for the crimes. While being taken to the jail in Rison (Cleveland County), one escaped, and the other, identified as Bill Wiley Douglass, was hanged from a trestle on the Cotton Belt Railroad. Douglass was described as “a hunchback, with copper-colored face; he has always been considered a desperado, and is supposed to [have] led the gang to do the bloody work of last Saturday.”

While it was rumored that the members of the mob were African American, most believed that they were white. Six others had been jailed in Rison for participating in the riot, and as the jail was not very safe, the paper reported that “it is the general opinion that before morning all six will be suspended between terra firma and the clouds.” T. T. Johnson had died in the infirmary on August 23, and despite earlier references to C. T. Gray as the other one being wounded, a white man named Tom Handley was also in the infirmary with serious knife wounds. In a story published the following day, datelined Rison, August 25, the Gazette referred to the lynching victim as Will Wyatt, who was said to have been lynched on Sunday night (August 22); it was also reported that “the sheriff is pushing a search for the guilty parties with great determination.” Of the six men in jail, two were thought to be innocent. On August 26, the New Orleans Times Picayune again identified the lynching victim as Wyatt, this time calling him Bill Wyatt. On August 27, the Daily Graphic reported that the sheriff of Cleveland County, who had originally taken the four suspects to the jail in Camden (Ouachita County), had secretly transferred them to Pine Bluff. This article gives the date of the lynching as August 23.

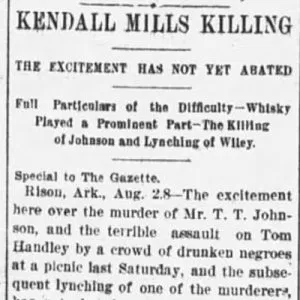

The August 29 edition of the Arkansas Gazette gives a more extensive picture of the incident, this time omitting that T. T. Johnson had gone to the picnic to find missing workers, changing the account of Johnson’s injuries, and leaving out all mention of C. T. Gray. Reportedly a group of around 500 African American workers from two large lumber mills, Kendall’s mill and Bluff City, were having a picnic on Big Creek near Kendall’s. The picnickers had put up a pavilion for dancing. A number of curious area whites went to the picnic to view the scene. Most of them left in the late afternoon, but five or six remained. Around dark, a white man named T. T. Johnson, described by the Austin Weekly Statesman as “a very prominent young man,” went to the picnic to buy some barbecue. While he was there, another white man named Tom Handley tried to get into the dancing pavilion. Handley encountered an African American named Moranzo Smith, with whom he had had an earlier altercation. Smith took offense and attacked Handley. Johnson intervened and offered to take Handley off the premises. Smith then hit Johnson over the head and crushed his skull. A dozen African Americans then attacked Handley and Johnson. A melee ensued, which lasted around fifteen minutes and during which most of the other Black attendees fled. Johnson and Handley were severely injured, and some white men who happened to be passing cared for them.

The following morning, Sheriff S. S. Dykes was informed and formed a posse to pursue the alleged murderers. On Tuesday night, they captured two of the Black men believed responsible. One of them escaped, but the other, identified here as Bill Wiley, was set to be returned to Rison on a hand car. When the group arrived at the Cotton Belt Railroad trestle, which was halfway between the two mills, they were stopped by a mob, who hanged Wiley from the trestle. Subsequently, three other African Americans were arrested and taken to jail in Camden for safekeeping. Moranzo Smith and another African American, identified only as Matthews, were still at large.

On August 26, the Pine Bluff Daily Graphic had commented on the situation. Noting that at times “people rise above the law and inflict punishment without appeal to the courts,” the newspaper cautioned that “this extraordinary power should be exercised only in cases attended with atrocious circumstances.” The editorial called the Cleveland County lynching “utterly unjustified and unjustifiable,” given that the victim (Wiley) was undoubtedly guilty and should have been left to the courts. In addition, white men were responsible for the melee and “should have known better than to be frolicking with negroes.” The editor went on to say that “wherever whiskey and ignorance come in contact, there is going to be trouble.” Thus, Johnson’s murder “was not such a one as would justify mob law.”

Some newspapers reported that a man named Tom Parker was lynched as a result of the same affair, but later reports backtracked from this initial assertion.

For additional information:

“Coloured Man lynched in Arkansas.” Baltimore Sun, August 26, 1897, p. 7.

“Crimes and Casualties: An Exciting Day.” New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 26, 1897, p. 2

“From Ear to Ear.” Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, August 22, 1897, p. 1.

“The Kendall Affair.” Arkansas Gazette, August 26, 1897, p. 3.

“Kendall Mills Killing.” Arkansas Gazette, August 29, 1897, p. 1.

“Mob Law.” Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, August 26, 1897, p. 2.

“Murders, Lynchings, and Assassinations by White Caps and Other Outlaws.” Crawfordsville Review (Crawfordsville, Indiana), September 4, 1897, p. 3.

“Riot Near Rison.” Arkansas Gazette, August 25, 1897, p.1.

“Spirited Away.” Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, August 27, 1897, p. 1.

“The Southern States.” Houston Daily Post, August 26, 1897, p. 4.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Wiley Lynching Article

Wiley Lynching Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.