calsfoundation@cals.org

Ban Humphries and Albert H. Parker (Murders of)

Sometime on the night of August 28–29, 1868, an African-American man named Ban (sometimes referred to as Dan) Humphries was killed near Searcy (White County). Reports indicate that he was killed by William E. Brundidge (sometimes referred to as Brundridge or Bundridge) and two other alleged members of the Ku Klux Klan. In September or October 1868, Albert H. Parker, who had been sent to White County to investigate the murder of Humphries and general Klan activities in the area, was also murdered.

These events were part of a larger pattern of upheaval surrounding the election of 1868. Arkansas had been readmitted to the Union in June of that year and would be able to participate in a national election for the first time since 1860. Democrats nationally believed they could win the presidency if the former Confederate states that had been readmitted to the Union supported their candidates—Horatio Seymour and Francis Preston Blair—against the Republicans Ulysses S. Grant and Schuyler Colfax. To do that, Southern Democrats had to break black voters away from the Republican Party. They did that by attempting to attract black voters to their party or by driving them away from the Republicans through the use of violence. To accomplish the latter, they encouraged the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in Arkansas and other Southern states. In March 1868, Arkansas held a convention, from which former Confederates were banned, to write a new state constitution. That same month, Republican Powell Clayton, a former Union general whom many regarded as a “carpetbagger,” was elected governor. In April 1868, the Ku Klux Klan began a campaign of nightriding, assassinations, and lynchings across the state.

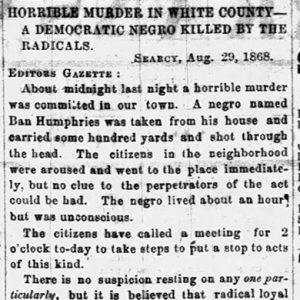

A September 1 article in the Arkansas Gazette, datelined Searcy, August 29, reported that around midnight the previous night Humphries had been taken from his home and shot in the head by unknown perpetrators. He lived for an hour but never regained consciousness. Humphries’s murder was clearly a political one, although from the beginning, Republicans and Democrats provided different explanations for what happened. Although there is no information about Ban Humphries in local records, there is some anecdotal information available. He had labored as an enslaved servant in the Confederate army from 1861 until 1863. According to Clayton’s book The Aftermath of the Civil War in Arkansas, “He was a very zealous rebel and used to boast of the many battles and skirmishes he was engaged in. After the war [it] was generally believed he was acting with the radical [Republican] party and was a member of their loyal league; but he took no active part and was generally very quiet.” Clayton regarded Humphries’s murder as resulting from an assault upon state Senator Stephen Wheeler by two men. Humphries supposedly knew who was involved in the plot and reported its leaders to the authorities.

According to the Gazette, however, there was reason to believe that Humphries, whom Clayton described as a “an intelligent and very influential colored leader,” was killed by “radical loyal leagues, negroes or whites.” The newspaper reported that, a short time before his death, Humphries met with other area African Americans to plan a late August meeting in Searcy to organize the black Seymour and Blair Club to support the Democratic Party. According to the Gazette, “These facts drive to the conclusion that he was put away by members of his league to prevent the betrayal of their plans, which they feared. The citizens are desperately indignant, and I believe if the perpetrator would be found it would be impossible to prevent his execution by a mob.…The democratic negroes are so terrified that it is not believed they will venture to form their club.” Local citizens called a meeting on the afternoon of August 29 “to take steps to put a stop to acts of this kind.” In conclusion, the Gazette asked, “How long are these things to continue?”

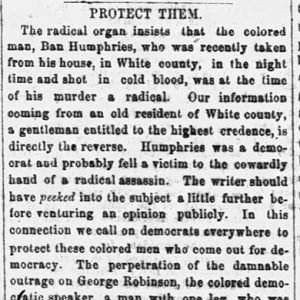

On September 5, the Gazette published a follow-up article on the situation. According to this report, the “radical organ” (probably the Little Rock Republican) insisted that “the colored man, Ban Humphries…was at the time of his murder a radical. Our information coming from an old resident of White county, a gentleman entitled to the highest credence, is directly the reverse. Humphries was a democrat and probably fell a victim to the cowardly hand of a radical assassin.…In this connection we call on democrats everywhere to protect these colored men who come out for democracy.”

Several years later, a White County man named Leroy Burrow testified that Brundidge told him that he, James W. Russell, and Howell Bradley, “under orders from Superior officers” (presumedly in the Klan), killed Humphries. The three were under the impression that Humphries was killed because “he was a leading and influential radical colored man in the county.”

Burrow, a native of Tennessee, had moved to White County by 1850. He served in the Thirty-Second Arkansas Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. W. E. Brundidge was probably the fifteen-year-old M. E. Brundidge who, in 1860, was living in White County with his parents, S. and M. Brundidge. According to newspaper reports, he moved to Texas shortly after Humphries’s murder; his obituary in a Fort Worth newspaper in 1930 reported that he had served in the Confederate army and had worked in Texas as a brick mason. Howell Bradley was in White County by 1860. He would later marry, work as a printer, and name his oldest child Frolich in honor of another alleged Searcy Klan member, Jacob Frolich. James Russell was born in Tennessee and served in an Arkansas unit during the Civil War. He would later marry W. E. Brundidge’s sister.

In the fall of 1868, Governor Powell Clayton hired twelve agents to investigate Ku Klux Klan activities in Arkansas. Among them was Albert H. Parker, a native New Yorker who had relocated to Texas sometime before the Civil War. Parker served in the Confederate army and, outraged by the activities of Confederate troops in Texas, moved for a time to Lawrence, Kansas, after the war. He then went to Little Rock (Pulaski County) to see his former commander, Major Samuel Walker, who had allied himself with the Republicans. Walker referred him to Governor Clayton. After examining Parker, Clayton sent him—posing as a cattle buyer—to White County to look into events there. According to later testimony, when Parker went to White County, he soon came to know several purported members of the Klan. They became suspicious of him, as he was spending a lot time mingling with Klan members and little time buying cattle. They alerted a Klan member who was working in the post office and had him intercept Parker’s letters. Parker then disappeared, and Frolich published articles in his newspaper declaring that Parker had left town and failed to pay his hotel bill. However, Parker’s body was discovered two months later in a well on a nearby farm.

A year and a half later, in late March 1870, details about how Parker had met his end began to emerge when F. M. Chrisman (a former Confederate officer, a friend of Clayton’s, and newly appointed circuit superintendent of public instruction) reported to Powell Clayton that he had encountered a man named Bunk (John Alexander) McCauley when they were forced to share a room in a crowded hotel in Searcy. A guilt-ridden McCauley confessed to Chrisman that he was involved in Parker’s murder. McCauley’s later testimony (probably in the November 1871 trial of three of the alleged perpetrators) tells the story. According to McCauley, he was raised in neighboring Independence County and served in the Confederate army for the duration of the Civil War. In April 1868, at the age of twenty-two, he joined the Searcy den of the Ku Klux Klan. He was initiated into the group by Jacob Frolich, editor of the White County Record, whom he said later became the Grand Titan of the Klan in the congressional district. In June of that year, McCauley was named adjutant general of the Klan under prominent lawyer Dandridge McRae, whom he identified as commander or Grand Titan. As such, McCauley was tasked with organizing new dens, and he named several other local Klan members. Among these were attorney John G. Holland and W. P. Edwards. McCauley could not remember when he first met Parker, but the last time he saw him was in late September or early October 1868 (other accounts give the date as October 14). According to his story, Leroy Burrow, allegedly Grand Monk in the Klan, stopped him on the street in Searcy and ordered him to go to the springs near the courthouse square. McCauley quickly changed into dark clothing and arrived at the springs about fifteen minutes later with Burrow; both were armed. There, they met Holland, Brundidge, and Edwards, all armed. Shortly afterward, Russell appeared at the springs, having persuaded Parker to go there with him. Russell did not remain with the others, who quickly gagged Parker and took him to a farm that he calls the “McConihe place” (sometimes called the McConnaha place) about three-quarters of a mile away. There, they shot Parker, threw his body into a well, and covered it with wood.

Hearing McCauley’s revelations, Governor Clayton sent the adjutant general of the state militia, Keyes Danforth, to arrest the alleged murderers. Although Ray D. Rains places these events in early April, McCauley remembers being arrested on a Sunday, perhaps March 21. (However, March 20 was the closest Sunday to this date.) Danforth took him to Little Rock, where he was introduced to Powell Clayton before being incarcerated in the Pulaski County Jail. That night, Governor Clayton and Stephen Wheeler came to see him to discuss the case. At first, McCauley claimed to know nothing about it, but when the men informed him that someone had already confessed and gave him details of the crime, he told them what he knew. They also implied that Leroy Burrow was ready to turn state’s evidence. McCauley recalled that Burrow was put in a nearby cell on Friday evening (March 25), that Russell was brought in that evening, and that Holland and Edwards were jailed on Saturday, March 26. All were indicted in White County during the spring 1870 term of the circuit court. Arrest warrants had also been issued for Dandridge McCrae and Jacob Frolich, but as they were going to Little Rock to face the charges, they received notice that they would be jailed without bail. Frolich went to Canada, where he worked as a printer for eight months, and McRae returned to his native Louisiana. They returned later to face charges when it became possible to obtain bail.

It is interesting to note that many of the men who allegedly murdered Parker were quite young at the time. Three of them—Holland, McCauley, and Brundidge—were in their early twenties. Russell and Edwards were barely over thirty. Even the alleged Grand Titan, Dandridge McCrae, was only thirty-seven. With the exception of Edwards, all had served in the Confederate army during the Civil War. McCauley reportedly served two different stints, both times when he was underage.

According to Rains’s account of events, on January 10, 1871, Edwards, Holland, and Russell were put on trial in DeValls Bluff (Prairie County) after a change of venue. At the trial, their attorneys requested and got a continuance, and they were released on bail. In late August, 1871, McRae and Frolich were tried in the White County circuit court as accessories after the fact. In his 1897 account of “Reconstruction Days,” McRae said that his indictment had been influenced by Republican F. M. Chrisman, who had intimidated the grand jury. He also declared that “not one scintilla of evidence” connecting him to the crime was ever produced. Due to lack of evidence—and also because McCauley pleaded the Fifth and Burrow, who had not been subpoenaed, did not testify—McRae and Frolich were acquitted.

This trial caused so much controversy that Judge Sol. F. Clark published a defense of the verdict in the Arkansas Gazette. Decrying reports in the Little Rock Republican that McRae and Frolich had been indicted for the actual murder of Parker, Clark notes that the two were charged only as accessories after the fact and that “no witness before the grand jury that found the indictment swore a word or syllable implicating either of these parties as having either known of or concealed the murder, or as having any connection in any manner with it.” They were indicted because “it was ordered by Clayton and his coadjutors, of whom McClure [Arkansas Supreme Court justice John McClure, a staunch Clayton supporter] was one, at Little Rock. It was a matter of state policy. These men were of standing in their community and prominent democrats.…They must be driven from the county, or their influence destroyed among their people.” The outcome was predetermined, as the prosecutor had failed to subpoena Burrow, and told the jury “that he could not make out a case, and directed them to find a verdict of ‘not guilty,’ which they did without leaving the box.”

By early November 1871, Russell, Holland, and Edwards were once again on trial in DeValls Bluff. The jury voted unanimously for their acquittal. The Memphis Daily Appeal described the three as “among the best citizens of Searcy,” and their acquittal was reportedly “hailed with the liveliest satisfaction by all the people of White River County.…Their trial and acquittal closes out the ku-klux trials in this section.…We are now free, breathe free, and feel free.”

Those allegedly connected to the murders of Humphries and Parker long outlived their victims. Jacob Frolich died in Little Rock in 1890 after a distinguished career in politics and journalism. John A. “Bunk” McCauley died in Louisiana in 1897. William Brundidge died in Fort Worth, Texas, where he relocated shortly after Humphries’s murder. A number of the men remained in White County. Attorney Dandridge McRae died in Searcy in 1899, James Russell in 1901, and John G. Holland in 1906. Leroy Burrow died in White County in 1900, and W. L. Edwards in 1915. Commenting on the outcome of the various trials, Powell Clayton declared: “It is a monstrous proposition that five men called ‘Yahoos’ should have been vested with power to seal the fate of an American citizen, and take the life of a man doomed by their decision and then, by the very strength of the organization on whose behalf they acted, escape the consequence of their awful crimes.”

For additional information:

“Arkansas.” Memphis Daily Appeal, August 30, 1871, p. 1.

“Capt. Brundidge dies in Fort Worth.” Cleburne Morning Review (Texas), June 6, 1930.

Clark, Sol. F. “White County Circuit Court.” Arkansas Gazette, September 7, 1871, p. 1.

Clayton, Powell. The Aftermath of the Civil War in Arkansas. New York: Neale Publishing, 1915. Online at https://www.loc.gov/item/15004463/ (accessed March 6, 2024).

“Horrible Murder in White County—A Democratic Negro Killed by the Radicals.” Arkansas Gazette, September 1, 1868.

“No Ku-Klux.” Memphis Daily Appeal, November 4, 1871, p. 1.

“Protect Them.” Arkansas Gazette, September 5, 1868, p. 2.

Rains, Ray D. “The Murder of Albert Parker.” Frontier Times Magazine 50 (June-July 1976). Reprinted in White County Heritage 60 (2022): 11–19. Online at http://bapresley.com/bishop_nelson/parker/ (accessed November 10, 2021).

Ross, Margaret. “Retaliation against Arkansas Newspaper Editors during Reconstruction.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 31 (Summer 1972): 150–165.

Testimony of “Bunk” M’Cauley. Testimony Taken by the Joint Select Committee to Inquire Into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States, Miscellaneous and Florida. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1872. Vol. XIII, p. 372ff.

Testimony of Le Roy Burrow. Testimony Taken by the Joint Select Committee to Inquire Into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States, Miscellaneous and Florida. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1872. Vol. XIII, pp. 362–363.

“White County Arrests.” Arkansas Gazette, April 8, 1870, p. 2.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Law

Law Call for Protection

Call for Protection  Ban Humphries Murder Letter

Ban Humphries Murder Letter

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.