calsfoundation@cals.org

312th Field Signal Battalion’s Pigeon Department

During World War I (1914–1918), homing pigeons emerged as a viable way for militaries to maintain contact when electronic communications failed. Most European armies maintained pigeon services during the conflict, yet when the United States entered the war in April 1917, its military lacked a comparable service. U.S. Army officials soon learned from their Allied counterparts the benefits of a pigeon post and established their own, with the Signal Corps assuming responsibility over the new department.

To fill the pressing need for pigeons, the Signal Corps began implementing pigeon programs at 110 army posts throughout the country. On November 30, 1917, Major Walton D. Hood received authority to command Camp Pike’s signal corps unit, the 312th Field Signal Battalion. Notices published in the Arkansas Gazette in early 1918 specifically sought “patriotic and footloose” men experienced in handling pigeons.

The 312th’s pigeon department became established over the ensuing weeks. In February 1918, preliminary lofts were installed on North Boulevard, near the rear of the 312th’s quarters. A few weeks later, the lofts were moved to a hill facing the camp’s trench system to acclimate the birds to trench warfare. In mid-March, the camp received a delivery of seventy-four mated birds. Training did not commence, however, until these pigeons had produced offspring. At eight weeks old, the fledgling birds were taken to a location a few miles away via motorcycle and released. Over time, the distance was increased to thirty miles. The fastest pigeons flew back to the camp at approximately a mile a minute.

The unit’s service members known collectively as pigeoneers eventually grew to fifteen, made up mostly of Midwestern men; only one hailed from Arkansas. One pigeoneer, a Belgian national, brought valuable knowledge to the group, as he had been a so-called pigeon fancier in his native country and lost his flock to the invading German army. Aside from caring for and training the pigeons, the pigeoneers also trained officers and enlisted men in techniques for proper message delivery.

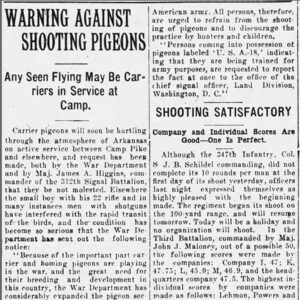

Amidst this backdrop was a concerted media campaign to prevent civilians from shooting pigeons. As early as February, notices started appearing in local papers. By April, President Woodrow Wilson had signed a federal law prohibiting shooting of all pigeons. In June, a grim story surfaced that over fifty pigeons belonging to the Thirty-ninth Signal Division at Camp Beauregard, Louisiana, had been shot that month. An investigation conducted at Camp Pike in July determined that no pigeons had been killed near Little Rock (Pulaski County).

None of the camp’s pigeons made it overseas before the war’s end on November 11, 1918. Camp Pike auctioned them off to the public in January 1919. While they did not serve on the frontlines, Camp Pike’s pigeons and pigeoneers formed a small, yet essential part in the formation of the U.S. Army’s Pigeon Service, which would exist until 1957.

For additional information:

“Camp Pigeon Training Considered Important.” Arkansas Democrat, May 18, 1918, p. 9.

“Carrier Pigeon Experts Needed.” Arkansas Democrat, January 4, 1918, p. 12.

“Carrier Pigeons Are Safe in Little Rock.” Arkansas Democrat, July 27, 1918, p. 9.

Craig, Justin. “‘Little Feathered Heroes’: Camp Pike’s Pigeon Service, 1917–1919.” Pulaski County Historical Review 71 (Winter 2023): 109–114.

“Homing Pigeons Arrive at Camp.” Arkansas Democrat, March 29, 1918, p. 4.

Office of the Chief of Signal. Report of the Chief Signal Officer to the Secretary of War. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1919, pp. 338–339.

“Pigeon Quarters to Be Ready Soon.” Arkansas Gazette, February 12, 1918, p. 3.

“Pigeons to Join the 87th.” Arkansas Gazette, February 5, 1918, p. 3.

“Prepare to Train Young War Birds.” Arkansas Gazette, March 22, 1918, p. 3.

“Seventy Pigeons Sold.” Arkansas Democrat, January 21, 1919, p. 6.

Justin Craig

North Little Rock, Arkansas

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Military

Military Pigeon Safety Article

Pigeon Safety Article  Pigeon Shooting Article

Pigeon Shooting Article  Pigeon Training Article

Pigeon Training Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.