calsfoundation@cals.org

John Steven (Steve) Clark (1947–)

aka: Steve Clark

John Steven (Steve) Clark was the longest-serving attorney general in Arkansas history. After eleven years as attorney general, Clark announced in January 1990 that he would run for the Democratic nomination for governor. A few days later, the Arkansas Gazette reported that his office had spent a suspicious $115,729 total on travel and meals, more than any of the other six constitutional officers, and that his vouchers listed many dinner guests who said they had not been his guests. In February, Clark withdrew from the governor’s race (Governor Bill Clinton would be re-elected). He was convicted of fraud by deception and resigned as attorney general.

Steve Clark was born on March 21, 1947, in Leachville (Mississippi County) to John W. Clark and Jean Bearden Clark. His father farmed, sold real estate, and engaged in local politics. Clark decided early that he wanted to be a politician. He graduated from Arkansas State University (ASU) in Jonesboro (Craighead County) with a degree in political science and French, and he received a law degree at the University of Arkansas School of Law in Fayetteville (Washington County) in 1971. Following that, he briefly practiced law in Brinkley (Monroe County).

In 1973, at the age of twenty-five, Clark became assistant dean of the University of Arkansas School of Law, where he met and became fast friends with a new law instructor, William Jefferson Clinton, and then a year later with Clinton’s future wife, Hillary Rodham, who had joined the faculty. Both men were handsome, charismatic, progressive in their philosophies, and ambitious. When Clinton was elected attorney general in 1976, Clark left the law school to become chief of staff for Governor David Pryor. When Clinton was elected governor two years later, Clark was elected attorney general, narrowly defeating state representative Art Givens in the Democratic primary.

Clark remained popular for the next decade, a turbulent period when Clinton was defeated and reelected amid a high turnover rate in state offices. Clark had no serious challenges in 1980, 1982, 1984, or 1986. His office received high marks for its aggressive consumer advocacy in utility matters and in commercial investigations by its consumer protection office.

He argued eight cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, but the highest-profile case never reached the Supreme Court. In 1981, the legislature passed—and Governor Frank D. White signed—a bill (Act 590) requiring the biblical account of creation to be taught in the schools whenever evolution was discussed—a so-called “balanced treatment” of theories of the earth’s beginning. The American Civil Liberties Union sued the state in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas (McLean v. Arkansas Board of Education) alleging that the law was unconstitutional because it had no purpose other than the establishment of religion and that it infringed upon academic freedom. Although Clark had warned legislators that the law could be challenged on constitutional grounds, he defended it.

The trial was followed internationally although it was not quite the spectacle of Tennessee’s famous Scopes Monkey Trial in 1925. Clark set out to avert the Scopes circus by barring the leading creationist lawyer—Wendell Bird of Atlanta, Georgia—from the defense team, refusing to call some witnesses for the biblical story of creation, and limiting the scope of the defense to efforts to explain creationism as legitimate science rather than the sacred word of God, the only conceivable ground upon which he thought the statute might be upheld. Clark encountered intense criticism throughout the trial and afterward from religious organizations and creation-science proponents such as the Institute for Creation Research, which said he was intentionally undermining the state’s defense of the law. He was denounced by television evangelist Pat Robertson on the popular 700 Club show.

Unlike the Scopes trial or the earlier evolution trial in Arkansas (Epperson v. Arkansas), Clark and the ACLU put on extensive testimony about the scientific validity of evolution versus creationism. In the 1981 case, U.S. District Judge William R. Overton cited scientific evidence gleaned from the trial to declare the law an unconstitutional effort to establish religion and to restrict freedom of speech and academic freedom. Clark said Overton’s opinion was so thorough and precise that it offered the state no chance of succeeding on an appeal, and he did not lodge one. While creationists said his decision proved he was never sincere about defending the law, they counted on another evolution trial in Louisiana, where the legislature had enacted a slightly different version of the law. Wendell Bird, barred by Clark from the Arkansas trial, did get to defend the Louisiana law in a federal trial (Edwards v. Aguillard). The U.S. Supreme Court held the law unconstitutional in 1987.

In January 1990, Clark announced that he would run for governor. Bill Clinton, who was toying again with a race for president in 1992 (he had backed out of the 1988 race after calling a press conference to announce his plans), said he would run for governor one more time. A few days later, the Gazette published an article about the expenses of state constitutional officers, which showed Clark with more business travel and meal expenses than the others. The article listed several examples of meals at Little Rock (Pulaski County) restaurants and the guests shown on the vouchers. The guests said they were not at the lunches, and when the newspaper inquired further, many others did, too. Ironically, Clark was not required by law to list his guests at business lunches, so the effect was that he self-reported his deceptions. He insisted that he had not violated the law.

The Pulaski County prosecuting attorney said that Clark had misused funds, using his credit card to charge the state about $8,000 for meals with his family, friends, and political contributors instead of people with whom he was doing state business. Clark was charged with felony theft by deception. He had already quit the governor’s race, three weeks after his announcement. A Pulaski County jury handed down a verdict on November 1, 1990, of illegally spending up to $2,500 of state funds and fined him $10,000 and court costs. He resigned his office and surrendered his law license.

Humiliated and broke, Clark moved to Jonesboro and appealed his conviction. When that failed, he moved around from Georgia to Florida to Tennessee to Texas, clerking in a bookstore; working for a home health company; teaching criminal law at a Miami, Florida, law school; starting a business; and practicing law in Texas.

He confessed that he had indeed committed a crime, and in 1996, he petitioned Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee for a pardon. He had telephoned many people in Arkansas—political foes, newspaper reporters, friends, and supporters—to apologize for disappointing them and embarrassing the state. He attributed his misdeeds to hubris and alcohol; he had stopped drinking in October 1994. On Clark’s fourth try, in 2004, Huckabee called Clark at his Austin, Texas, law office to tell him he was pardoned.

In Austin, he met the woman who became his third wife: Suzanne Greichen of Newport, Rhode Island, who was a chemical engineer and subsequently became a lawyer. By that time, he had two daughters from a previous marriage. The couple moved to Fayetteville, and in 2008, Clark ran unsuccessfully for mayor of Fayetteville. After losing that race, Clark became president and chief executive officer of the Fayetteville Chamber of Commerce.

For additional information:

Brummett, John. “Clark: New Man, Old Pursuit.” Arkansas Times, April 24, 2008, p. 17.

Davis, J. R. “Redemption.” Talk Business Arkansas (November/December 2013) 26–30.

Robertson, April. “John Steven Clark.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 10, 2016, pp. 1D, 5D.

Webb, Kane. “Steve Clark’s Return.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 12, 2008, pp. 1J, 6J.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Clark and Representatives

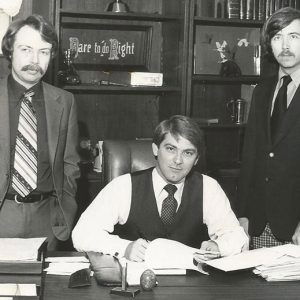

Clark and Representatives  Clark Staff

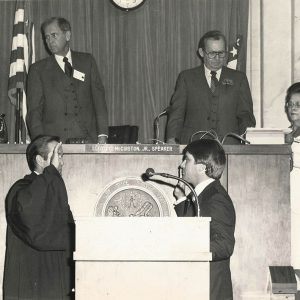

Clark Staff  Steve Clark Being Sworn In

Steve Clark Being Sworn In  Steve Clark

Steve Clark  Steve Clark and Staff

Steve Clark and Staff

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.