calsfoundation@cals.org

Skipper v. Union Central Life Insurance Company

aka: William Franklin Skipper (Murder of)

aka: Monticello Lynching of 1898

The death of William Franklin Skipper near Baxter (Drew County) in 1896 sparked a series of trials the Arkansas Gazette described as “perhaps the strangest case in the criminal annals of Arkansas.” The only certainty in the case seems to be that Skipper, a merchant and sawmill owner and a partner in the firm of Skipper and Lephiew (sometimes spelled Lephlew), died of a knife wound to the neck beside Bayou Bartholomew sometime on May 13, 1896. During the two criminal trials, much of the argument centered on whether he committed suicide or was murdered by a group of African-American men who worked at his mill. The criminal case dragged on for more than two years. The Arkansas Supreme Court overturned the convictions of two of the sawmill workers—James Redd and Alex Johnson—twice, but the men were killed in their cells by a mob before they could have a third trial. In a parallel series of trials, which lasted into the next century, Malissa Skipper, the dead man’s widow, took her case against the Union Central Insurance Company of Cincinnati, Ohio, to federal court seeking payment on her husband’s life insurance policy, a case complicated by the lynching of the defendants.

The first news of Skipper’s death appeared in the Arkansas Gazette on May 14, and a more extensive report followed on May 17. According to this second account, Skipper was found on the bank of a bayou “near his saw mill, a half mile north of here [Baxter], his jugular vein punctured and an open knife in his hand.” While the Gazette and many other newspapers reported that the verdict of the coroner’s jury was suicide, Drew County justice of the peace and acting coroner H. Lewis had actually ruled only that Skipper “came to his death…by a knife wound in his throat.”

Because of heavy rain, the bayou water level was high at the time of Skipper’s death. When it receded, further investigation revealed footprints, signs of a struggle, and drops of blood on the logs. On May 20, James Redd, Alex Johnson, Sam Lusk, and John Bradford were charged with murder, and Frank McKay as an accomplice. Johnson, McKay, Lusk, and Bradford were eventually released. Bradford and Lusk promptly disappeared. Johnson returned to his job at the sawmill, where he continued to work until June 7. At that time, feeling he was in danger, he went to St. Louis, Missouri, for two months. Upon his return, Skipper’s former partner, William H. Lephiew, hired Johnson back at his old job at the sawmill. According to historian Donald Holley, however, Lephiew believed all along that Skipper had been murdered and finally called in private investigators to look into the case. This resulted in Johnson’s arrest later in the summer on a charge of murder. It is unclear whether Redd was ever released, but by late summer he was in jail with Johnson, also charged with murder.

The trial was held in Drew County Circuit Court in September 1896. By this time, the charges against Frank McKay had been dropped, and he appeared as a witness against Redd and Johnson. The prosecution contended that Redd and Johnson had engaged in a conspiracy to lure Skipper to the bayou in order to rob him of some money he was carrying to pay for timber. After robbing Skipper, they supposedly placed a sack over his head and pushed him into the bayou. When he struggled and yelled for help, someone cut him across the throat with a razor. Skipper managed to crawl back to the bank, where he was stabbed in the neck yet again, which proved fatal. The murderers then allegedly escaped from the area by wading along the edge of the bayou with pads on their feet. The prosecution’s case relied heavily on the testimony of John Henry, a convicted felon who was in jail with Redd after Redd was arrested. Although the defense objected to his testimony on the grounds that the prosecution could not prove that Henry had been pardoned, and thus was eligible to testify, Henry’s testimony was admitted.

The defense contended that Skipper had committed suicide, and that, if he had indeed been murdered, it was not at the hands of Johnson and Redd. They based the idea of suicide on the fact that Skipper was in financial trouble and not in good health. Redd testified that he had gotten up at 5:00 a.m. the morning of Skipper’s death, gone to Louis Handley’s house near the mill for breakfast, and then gone to work at the mill. He did not see Skipper all day and denied making statements to either John Henry or Frank McKay. According to his testimony, Redd first heard about Skipper’s death late on the afternoon of May 13 when it was reported at the mill. Alex Johnson, a fireman at the sawmill, also denied seeing Skipper on the day of his death. Despite the circumstantial evidence and the defendants’ vigorous denials, both Redd and Johnson were convicted of murder and sentenced to hang.

The Arkansas Supreme Court heard arguments on appeal in February 1897. It is worth noting that Redd and Johnson had excellent legal representation for both this appeal and the subsequent one. One of the attorneys was H. King White of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), a former state senator who has been referred to as “one of the best known lawyers of the state…one of the most fearless men in Arkansas and…always ready to stand up for his convictions.” The second lawyer was Joseph Warren House, a former state senator, circuit court judge, and U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Arkansas.

Redd’s conviction was upheld, the court finding that there was only scant evidence that Skipper had committed suicide and that Redd’s confession, although it had been given to a fellow prisoner, was enough to justify a guilty verdict. Johnson’s conviction, however, was overturned due to a lack of evidence linking him to the crime. In April, however, the court reversed itself,finding that a confession was not enough to convict Redd in the absence of strong corroborating evidence, so both Redd and Johnson were granted new trials.

In the meantime, Malissa Skipper was pursuing her suit against the Union Central Insurance Company. She first filed it in Drew County Circuit Court in early December 1896, but the suit was dismissed on February 19, 1897. She then re-filed it in the U.S. Circuit Court in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1897. The trial was held in May, and the result was a mistrial because the jury was unable to reach a verdict. One of the attorneys representing the insurance company in this case was J. W. House, who was also defending Redd and Johnson in the criminal case at the time. The Gazette made note of the unusual circumstances surrounding the case, in that if the insurance company failed to prove suicide in federal court, “they lose their case; on the other hand, proving suicide will have no effect upon the sentence of murder passed upon Redd for the murder.”

In September 1897, in preparation for Redd and Johnson’s second trial in Drew County circuit court, Governor Daniel Webster Jones pardoned two convicted burglars, Jim Robinson and Jim Gaskins, whom the prosecution believed could provide material facts in the case; the pardons restored their citizenship so that they could legally testify. At the same time, Malissa Skipper’s second suit against the Union Central Insurance Company was scheduled to go to trial on November 14. In the meantime, the witness John Henry had died, but his prior testimony was read to the jurors during the murder trial. James Robinson actually claimed to be an eyewitness to the murder, adding that Johnson threatened his life if he talked about it. On November 27, 1897, Redd and Johnson were once again convicted and sentenced to hang on December 31. The Arkansas Supreme Court issued a last-minute stay, however, pending a new appeal. Meanwhile, Malissa Skipper’s suit against the insurance company ended in a hung jury.

The second appeal in the criminal case was heard in April 1898, and the decision was announced on July 9. The circuit court’s decision was reversed once again, and Redd and Johnson were granted yet another new trial. The appeal was based largely on the fact that two convicted felons, John Henry and James Robinson, neither of whom provided the court with official copies of their pardons, were allowed to testify without conclusive proof that they were eligible to do so. John Henry’s widow, Elvina, testified that her husband said he had lied to authorities about Redd and Johnson in order to obtain his own release from prison. J. J. Bowles of Reedville (Desha County) bolstered the suicide theory, testifying that Skipper had told him that he had “very little left to live for” and that his family would be better off without him. The court upheld the lower court’s actions in all but one particular: the defense had once again used the testimony of John Henry, and once again had failed to produce actual proof of his pardon.

Redd and Johnson, who had spent much of 1897 in the state penitentiary, had by this time been returned to the Drew County jail in Monticello. Apparently by this time, the citizens of Drew County were ready to exact their own form of justice. At 3:00 a.m. on July 14, while Sheriff J. H. Hammock was away and the jail was being supervised only by jailer J. W. Parish, a mob gathered outside and demanded the prisoners. When Parish refused, several men broke down the door of the jail. They intended to remove Redd and Johnson from their cells and lynch them, but the prisoners fought back so fiercely that the intruders gave up and “poured a volley of shots into the cages where the men were confined.” Johnson was killed instantly, and Redd was fatally wounded. According to theAdvance, as Redd lay dying, a number of local men and boys surrounded the cell to stare at the “gruesome spectacle.”

In the meantime, Malissa Skipper’s case was still making its way through the courts. In an interesting twist, her lawyer appeared again in U.S. Circuit Court on August 17, 1898, to move for a non-suit, which was granted without prejudice. She re-filed her case three days later, on August 20. The case was tried once again in federal court in December 1899. Again, after four days of deliberation, the jury could not reach a verdict. The Insurance Register had the following comment on the case: “Curiously the defendant [Union Central Life] is not convinced that Skipper was murdered because two negroes were twice convicted and finally shot to death in their cells by a mob. If only guilty negroes were convicted and shot to death in the South its view might be different.”

The case was heard yet again in the U.S. District Court in Little Rock in November 1900. The court found in favor of Skipper, and she was awarded $12,600, which included the face values of the insurance policies, accrued interest, and legal costs. Union Central appealed the court’s verdict to the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in March 1901. A year later, the judgment of the lower court was upheld. Skipper finally received her money on June 5, 1902. Thus, after six years, the complicated series of trials resulting from the death of W. F. Skipper came to an end. Although Redd and Johnson had been convicted of murder twice in district court, both verdicts had been overturned by the Arkansas Supreme Court because of inadmissible testimony. Only in Skipper’s case against the insurance company was a definite determination of murder ever made. According to the Weekly Underwriter, “There has been a strange line of fatality and judicial controversy growing out of the case which promises to become as celebrated as the Hillmon case of Kansas.”

Malissa Skipper was to have an interesting future. William H. Lephiew’s wife, Delia, died in 1900. In 1901, Lephiew and Skipper, who had continued the business partnership begun by her husband, were married. They lived in nearby Dermott (Chicot County) until his death in 1931 and hers in 1933. Both are buried in Monticello’s Oaklawn Cemetery, but beside their first spouses. Skipper’s insurance case lives on in U.S. insurance law and has been used as precedent in the U.S. District Court of Appeals as recently as 1981.

For additional information:

“Arkansas Insurance Case: Widow of Dead Man Says He was Murdered.” The Republic (St. Louis, Missouri), March 17, 1901, p. 8.

“Fined $500 for Contempt.” Arkansas Gazette, December 5, 1900, p. 8.

“H. King White.” In The Province and the States: Biography, vol. 7, edited by Weston Arthur Goodspeed. Madison, WI: Western Historical Association, 1904.

Holley, Donald. “Three Dead Men and $10,000: A Drew County Mystery.” Drew County Historical Journal 8 (1993): 4–11.

“In the South: Skipper vs. Union Central Life.” Insurance Register (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), December 14, 1899, p. 379.

“Insurance in the Courts.” Weekly Underwriter, December 18, 1900, pp. 353–354.

“Into His Throat.” Arkansas Gazette, May 17, 1896, p. 6.

“Mob Kills Two Negroes in Jail.” Atlanta Constitution, July 15, 1898, p. 7.

“Mrs. Skipper Wins.” Arkansas Gazette, December 5, 1900, p. 8.

“No Parallel: Skipper Case Without a Counterpart.” Arkansas Gazette, July 16, 1898, p. 3.

“Redd et al. v. State (Supreme Court of Arkansas, Feb. 20, 1897).” In Southwestern Reporter, vol. 40. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Company, 1897.

“Redd et al. v. State (Supreme Court of Arkansas July 9, 1898).” In Southwestern Reporter, vol. 47. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Company, 1899.

“Remarkable Case.” Arkansas Gazette, April 21, 1897, p. 5.

“Skipper Case Decided.” The Insurance Press, December 12, 1900, p. xixvii.

“The Skipper Case.” Arkansas Gazette, September 17, 1897, p. 8.

“Skipper Case Withdrawn.” New York Times, August 18, 1898, p. 7.

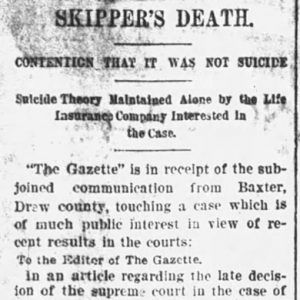

“Skipper’s Death.” Arkansas Gazette, May 7, 1897, p. 2.

“Union Cent. Life Ins. Co. et al. v. Skipper.” In United States Circuit Courts of Appeals Reports, vol. 1-171. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Company, 1902.

“Will Not Be Hanged Today.” Atlanta Constitution, December 31, 1897, p. 5.

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 William Skipper Article

William Skipper Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.